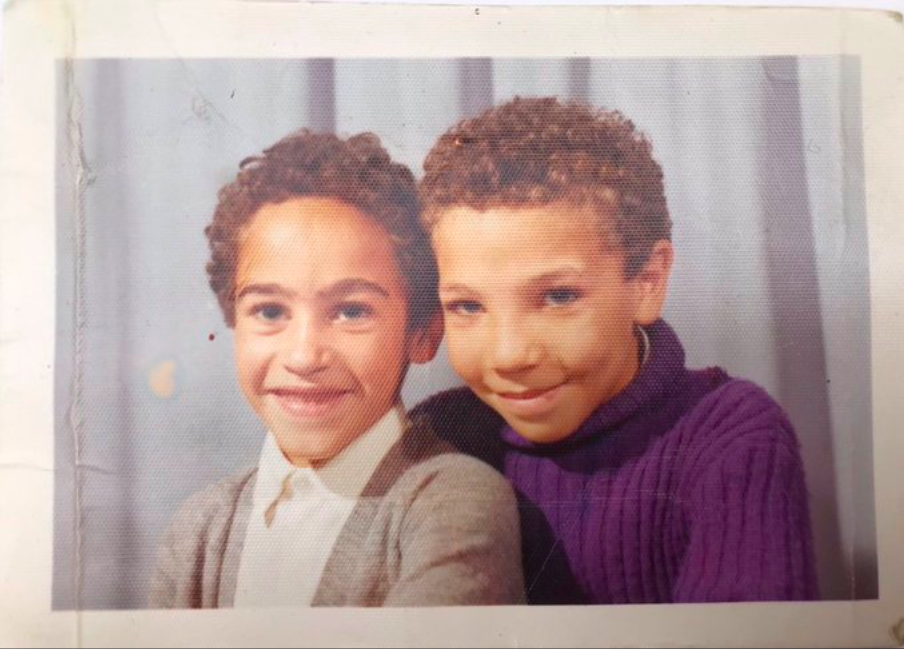

Photography courtesy of Anthony Lennon

Last week Anthony Lennon, a theatre-maker who made headlines back in 2018 for participating in a scheme for BAME people in theatre, despite having two white parents, shared new personal findings regarding his heritage. That’s right, he just took a DNA test – turns out, he’s “32% African”. The case has caused a huge amount of emotional uproar, furore, and for some, plain confusion, as we’ve debated over not just one man’s racial identity, but what it says about race more broadly. And the answer is, of course, it’s very complicated.

First and foremost – more than anything, Anthony’s case serves to expose that race is a social construct. The range of opinion, argument and emotion expended on justifying whether he “qualifies” as black is the clearest evidence for this. What constitutes blackness, is it parentage? Culture? Biology? Social perception? When we approach race as a social construct, we should instead conceptualise it as method of social organisation that was constructed by white people, colonialists and eugenicists and isn’t grounded in any material scientific reality.

Any social construct that seeks to draw hard lines on what it means to sit inside, or outside of its fault lines will surely fail. Which is part of the reason why Anthony’s case has confused many – there is no single, observable, binary metric that determines race, other than being racialised by society. This can sometimes be subjective, which is why stories of racial ambiguity prove so endlessly fascinating. gal-dem writer Georgina Lawton – who was raised by white parents but later discovered her biological father was black – but also celebrities like Meghan Markle, Rashida Jones and Maya Rudolph, have drawn attention to how being mixed or white-passing can in fact be a grey area. Race is invented, and looking to social settings like Brazil and the Caribbean gives us further evidence that notions of blackness and mixedness are culturally contextual. Nonetheless, with Anthony’s immediate family being white as far as he is aware, and being racially ambiguous but arguably white-passing, means that very few contexts would see him as a victim of racism.

“Anthony’s case has confused many – there is no single, observable, binary metric that determines race, other than being racialised by society”

But what about the DNA results? For some, evidence of Anthony’s potential faraway black ancestry was presented as straightforward “proof”. But in many ways, this doesn’t make the case any less complicated – the use of DNA tests only serve to further lean into the scientific racism we unpacked earlier. Can a person be a certain “percentage” of black anyway? Does genetic testing do anything to tell us something new about how we are seen and treated in a racist society?

Genetics don’t always have a bearing on how we are racialised. We gain entertainment from watching videos that teach us that white supremacists are part black, ultimately understanding that without these results they will live comfortable lives characterised by the structural advantages that come with being seen as white. We see Tom Jones pressured to take a DNA test to explain his tan and lifelong interest in gospel music. We hear that people are a tiny percentage Native American and squint to see arbitrary features we’ve been primed to see as belonging to certain racial groups – and meanwhile 23andMe is telling people they are 5% Neanderthal.

While DNA tests can gesture towards ancestry, as Georgina Lawton found in an article for gal-dem’s Guardian takeover, the science is unreliable and ultimately a blunt tool for understanding the ways that people are racialised in the real world. If anything, appealing to percentages and ideas of what’s in our “blood” only serves as a glorified version of the one-drop rule, the brown paper bag test, eugenic measurements or any other flawed metric that’s been used to remedy the issue that blackness isn’t a clear binary. As evolutionary genetics professor Mark Thomas remarked: “Let’s be honest, these companies are … trying to define biological races using this genetic data. That in itself is shifty.”

“The use of DNA tests only serves to further lean into scientific racism”

It’s worth considering that part of the emotion that surrounds the case of Anthony is of course also scarcity of resource (in this case, within the theatre industry), and the function of BAME schemes like the one Anthony was a part of. PoC communities are not always defined by clear cut boundaries, and where spaces exist for specific groups, a judgement call is often required on the part of individuals to assess the extent to which they are taking up space. I understand the anger on Twitter about changing his middle name to Ekundayo, and the theatre scheme; as someone who didn’t know for sure that he had any black ancestry, applying for a fund exclusively for BAME communities potentially sets a dangerous precedent.

Of his story, Anthony told gal-dem: “On the 28th November 1965 a baby of mixed (Irish and African) heritage was born to white parents. It’s happened before and will happen again. It’s an odd happening only to those who are not conscious of the history of genetics. After my birth various people identified me as needing care, education and inspiration in relation to both my Irish heritage and as much of a positive history appreciation of Africa as possible as part of my sense of self and well being. The rest was history. Until the media attack on me last November. I wasn’t born white to then morph into a black man or person of mixed heritage. I was born with white and black genes for all to see.”

There is good reason to discuss cases like Anthony’s, but what’s striking is how much airtime we seem to give individual cases over broader issues of systemic racism. For many reporters and readers alike, the case is “interesting” and “complicated” food for thought. But while racism and racialised violence still exists, we shouldn’t individualise our approach to the issues raised by Anthony’s story. Who is most likely to die at the hands of the state? Most likely to be subject to police violence, to be denied access to services? Race is constructed and affects all people of colour, beyond those contested, blurry boundaries.