Artist Kara Walker has gifted the UK a huge fountain to remind us of its role in the slave trade

Bolanle Tajudeen

01 Oct 2019

Photography by Ben Fisher

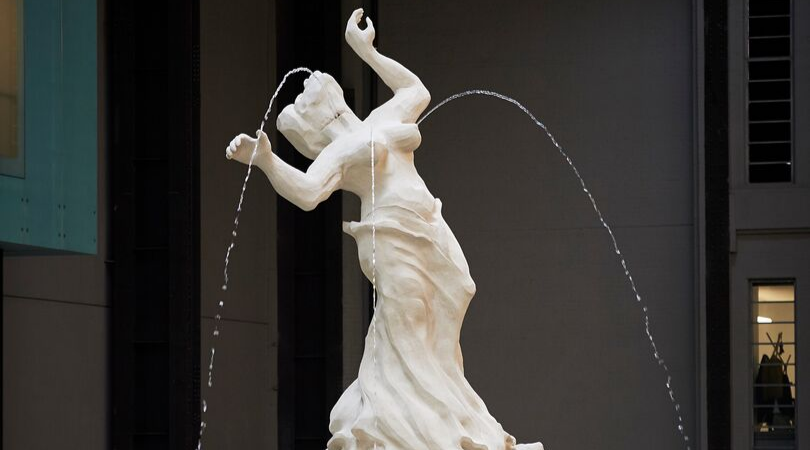

Fons Americanus, opening today at Tate Modern, is a visually painful spectacle. A sculpted noose hangs off a broken tree, and figurines of black bodies swim and drown amongst sharks. Topped with a liberated, reimagined Botticelli’s Venus, the piece shows how the indictment of colonialism and slavery historically anguished black life. The opening coincides with the with Nigerian Independence Day – one of the many countries ruled under the Commonwealth.

Kara Walker, best known for her controversial silhouette figures depicting the antebellum south and her giant sugar mammy, A Subtlety, is the fifth artist to be commissioned to install a new artwork at Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, and the first black woman. Next month, her work will be one of the focuses of a four-week course I will be leading at the Tate, examining the notions of black feminist art and how identity shapes artistic practices. But first, she has “gifted” Britain, who she refers to as “our captors, saviours and intimate family” with Fons Americanus – a four-tier working fountain resembling the Victoria Memorial at Buckingham Palace.

Having a work like this on display, which responds to the British Empire and reframes our past, is a great way to learn about art and black history. Littered with historical and contemporary art references, Kara has used a mixture of “fact, fiction and fantasy” and imposes on viewers a lesson of race, identity and violence; themes she has consistently dealt with in her three-decade-long artistic career in a variety of visual mediums.

Fountains and monuments are symbolic. The use of statues to decorate fountains gained prominence in Italy during the renaissance era, and the aesthetic quickly spread across Europe in the late 15th century as the wealthy felt it added beauty and art to outdoor spaces. Kara, who had a residency in Rome last year, has been inspired by the Trevi Fountain, the most famous fountain in the city which depicts the god of water, Oceanus. But she reimagines the fixture to bring life to the experiences of enslaved Africans – a version of history that has largely been rendered invisible.

“Kara has presented Britain with a confrontational account of its violent history imposed on the subjects of the British Empire”

The work is intended to ignite a debate about civic sculpture across Britain. Much of the time, the public passively engages with the symbols and markers presented monuments – taking in history in a leisurely or subconscious way. But Kara has presented Britain with a confrontational account of its violent history imposed on the subjects of the British Empire. It may not be a gift that Britain wants, but it is one that it needs – and should be thought about in relation to the Victoria Memorial, which was erected to honour a queen who reigned at a time Empire saw its largest expansion. It forces viewers to think about how histories are recorded, and how the powerful are enshrined in history, but the lives they devastate go overlooked.

It also exposes 19th-century propaganda by directly referencing The Voyage of the Sables Venus from Angola to the West Indies, a famous etching which whitewashed the horrors faced by enslaved Africans who were stolen and taken across treacherous waters to foreign lands.

The history of black women being forced to abandon their babies and become wet nurses for white babies is represented in how the water takes shape in the fountain: the water spouts from the bosom of Venus. Tate Modern Director Frances Morris described the fountain as a “mythical spiritual blessing” at a press meet. However, there is no blessing to be retrieved from the work. If it came to life, the Damien Hirst-inspired sharks would have feasted on the flesh of the black bodies. Horrifically, there’s evidence that sharks actually learned to follow slave routes because they fed on bodies thrown overboard.

“The history of black women being forced to abandon their babies and become wet nurses for white babies is represented in how the water takes shape in the fountain”

Botticelli’s Birth of Venus depicts Venus arriving ashore fully grown, and Kara’s Goddess mirrors this journey, made through the seas to land. But instead of being greeted and warmly welcomed, she has arrived at a place where she will be forced to spill milk, while blood oozes from her throat and rends her voiceless as it trickles down the pillars and basin below.

A part of me wished Kara Walker would have made the water spout from the eyes. Visitors being greeted by a weeping black woman among the carnage of the British Empire might have helped to humanise our existence.

Kara Walker: Fons Americanus is at Tate Modern, London, from 2 October 2019 to 5 April 2020

Art in the Age of Black Girl Magicis being held across Tate Britain and Modern 25 October – 16 November 2019