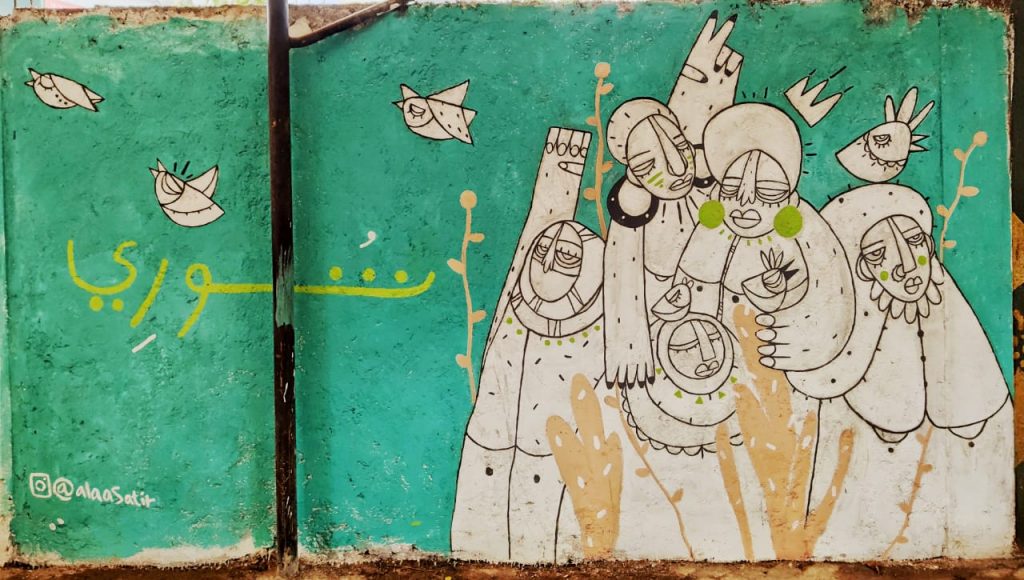

Mural by artist Alaa Satir /Photography Makki Rashid

I spent most of this summer immersed in researching the Sudanese revolution. On my journeys around Sudan, I was lucky enough to witness first-hand the transformations borne of 10 months of uprising. Physically, little has changed, and the revolution has yielded no miracles. Our streets remain lined with the remnants of neighbourhood protest barricades and revolutionary graffiti. Art is sprinkled throughout towns and cities. People continue to line the streets each morning, patiently waiting for bread, and petrol and cash are still scarce. But a major change has already taken place across the entire country, in the hearts and minds of the Sudanese people. How we view ourselves and one another has been transformed, and that is the revolution that matters most.

When I last wrote for gal-dem on 10 June, the situation in Sudan was devastating and dire. After months of peaceful protests, the people had overthrown génocidaire Omar Al Bashir on 10 April, and his complicit usurper Ibn Naouf was unseated the following day. Sit-ins had been established across the country and were maintained as protesters sought to ensure that the transitional military council worked towards civilian rule. These sit-ins became our “homes away from homes” and brought millions of people together in song, dance, poetry, discussions and awareness campaigns. They were mini-utopias scattered across Sudan.

Everything changed on 3 June. Our ecstasy turned to terror when militants violently destroyed the sit-ins, martyring, beating and maiming hundreds. The internet was swiftly cut off from the people on the ground, and I spent June worrying. Those who could left the country and Sudanese people in the diaspora started to talk about never being able to go back home.

What I couldn’t expect when I wrote the article was the miraculous events that followed. First, the international community stood up for the Sudanese people. Globally, people turned their social media profile pictures blue in solidarity with protestors. Petitions and letters were sent to politicians across the spectrum. Campaigns were coordinated and demonstrations were staged from Texas to London and Kuala Lumpur. Rihanna, Naomi Campbell and Yara Shahidi used their platforms and stood in solidarity with the Sudanese and gave us hope that we weren’t alone. Spurred on by this global recognition and, despite the huge obstacles of a social media blackout and the unbelievable trauma of the 3 June massacre, Sudanese people across the country turned out for the “millions march” on 30 June in greater numbers than the 6 April march which succeeded in toppling Al Bashir. This overwhelming show of peaceful mass determination forced the military leadership back to the negotiation table. The Sudanese people stuck together, stood together and are forever changed because of it.

Before the revolution, there was a state but no single Sudanese nation. Ever since the British administration, Sudan has been divided and ruled by self-serving “governments” that have kept Sudanese people apart, instead of fostering connections and unity in our awkward and colonially-configured country. Al Bashir’s government used this tactic of division based on outdated tribal identities, to cement their control. If their countrymen were not united under a single identity they could never challenge their rulers. Under Al Bashir’s regime, any form of national identification reminded you that your gabeela (tribal origin) still trumped the unity of the nation.

Consequently, there was little love or fraternity between those in the centre and those on the peripheries. State censorship ensured that we had little news of what happened outside of Khartoum, and, when we did, it was warped, often depicting ethnically African Darfuris as threatening rebels and Southern Sudanese as savage missionaries. Every mechanism at the government’s disposal was used to peddle the regime’s Arab-Islamic identity and racism was encouraged against those who did not conform.

Growing up, I couldn’t understand why no one took to the streets in Khartoum in response to the genocides of Darfur or the Nuba Mountains which left hundreds of thousands dead and millions displaced. Research has taught me about the extreme level of alienation between the different Sudanese people before this revolution. Not a single protester I interviewed in Khartoum reported being actively aware of the government-perpetrated violence in Darfur or the Nuba Mountains prior to the revolution. While some blamed the lack of free speech, most admitted to not looking into the problems because they felt totally disconnected from the cause. There was no sense that Darfuris were “our people” as several protesters explained to me. To say that we were a divided people would be an understatement.

Beyond overthrowing a tyrant, the Sudanese revolution broke down these barriers and connected people from all across Sudan. People from every region of Sudan gathered in the Khartoum sit-in and educated one another on their respective areas, histories and cultures. The sit-in gave us the long-overdue opportunity to meet and hear first-hand the stories the regime had kept hidden for decades. As protester Mohaned Mahgoub told me, “We had a completely different image. When I sat with people from Darfur, they told us all the stories, that they’d (the government) come to their village and kill everyone“. When the government tried to blame the revolution on trouble-makers in Western Sudan, protesters across the country rebutted, “We are all Darfur”. Murals both acknowledged and rejected the internalised racism that was so rampant in Sudanese society. The art at the sit-in celebrated the African side of Sudanese identity and the old flag was used, signalling a rejection of the Arab-Islamic connotations of our newer one. Despite all of the chaos, it was also a summer filled with quiet moments of reflection and introspection as people considered their complicity in the horrors that took place in Darfur and in the loss of the South in 2011.

The old regime made it physically impossible for us to know one another or to know this country. This summer I was lucky enough to travel to Darfur (Nyala) and the Nuba Mountains (Kadugli) for the first time, areas I have singularly associated with destruction my whole life. I was shocked by the beauty of Western Sudan in the rainy season. It was hard for me to process that this was Sudan, because I’ve been conditioned to have a very singular idea of what Sudan looks like, or at least the Sudan that “counts“. Sharing the pictures with my friends and family, their disbelief made me both sad because we are still strangers to our own country but also excited for the opportunities people will have in the coming years to get to know Sudan and all it has to offer. In both Nyala and Kadugli protesters were given a sense of belonging and connection to the centre by the protests. Hearing other Sudanese people chant “we are all Darfur” across the country, the revolution gave protesters renewed faith in the Sudanese nation.

I’m so proud and relieved that, although the sit-in was brutally destroyed, the spirit of unity and genuine fraternity has survived it. Sudanese people continue to protect not only revolution but one another. When the Khartoum sit-in was dispersed, Sudanese people protested across the country, knowing the potentially bloody repercussions. When four students were killed in El Obeid on the 29 July, it became a source of national outrage and action. When inter-tribal violence erupted in Port Sudan this month, leading to the deaths of dozens, revolutionaries marched 490km from Kassala to Port Sudan in solidarity with peace. When the peace-sharing agreement was finally signed on 17 August, Khartoum-dwellers waited in the sun for hours to give the train full of Atbara protesters the welcome they deserved. And when I finally arrived in Atbara, a train full of volunteers and donated supplies were travelling to Kosti to help with rain and flood damage.

We have a long way to go, but we’re hopeful and optimistic. How could we not be? Before 11 April, all my generation had ever known was dictatorship. Al Bashir came to power eight years before I was born and over three decades persecuted, oppressed and mismanaged Sudan into the ground. Today, he sits in prison as his trial continues. The transitional government has pledged to embrace Sudan’s diversity. Our prime minister, respected economist Abdalla Hamdok, is from Southern Kordofan. A Coptic Christian woman, Aisha Musa Saeed, sits on the sovereign council. The peace agreement ceremony was commenced by passages from both the Bible and the Quran. Women have been promised 40% of seats in the legislature and many like Asmaa Abdulla, our first-ever foreign minister who is a woman, will take up positions hitherto reserved for men.

Driving around Khartoum in my last few days, I noticed that people had begun painting murals again. Where the soldiers destroyed the sit-in’s art, artists were out re-painting their works. Once again my people are hopeful and ready to do their part in building the nation we’ve demanded. We’ll work to honour the sit-in and those who lost their lives there by keeping its spirit alive. We’ll protect and foster the connections built by this revolution and stop arguing about whether we’re African or Arab, because we’re all Sudanese. Political revolutions can be subverted, ours still faces threats on many sides. But now that we truly know one another, this revolution of awareness and fraternity is forever.