“You smell like curry”, a friend casually remarked as we entered the tube. It’s been over five years since high school, but those four words brought back haunting memories of being the kid who brought a “smelly” lunch to school. The comments clung to me like the smell of my food. Back then, my desire for my mother’s home cooked lunch was overpowered with my desire to fit in, creating an unhealthy relationship with Indian food. As a result, as soon as I was old enough to pack my own lunch, I started learning to make pasta and sandwiches.

Little did I know that, when I got older, the very people that were mortified by my packed lunches would come to embrace and love the same smelly food. I am sure some of you might be thinking, just like my white friends, “why would you reject my mother’s incredible authentic Indian food?” Well, because as a kid, being different because of the colour of my skin was enough to deal with. Worrying about the nuances of that difference, in this case the food I ate, was even more of a burden!

Anyhow, what can one say in response to my friend’s remark?

“Oh, you smell like under seasoned roast beef!” It sounds ridiculous, mostly because white people’s experiences have never been boiled down to their food. Unlike other communities of colour, white people have never been called racial slurs based on the food they consume, such as “curry people”. Comments about the “smelly” nature of the food people of colour consume have been the source of really hurtful stereotypes, which have affected all aspects of their life including, their ability to rent a house (because of the food they cook), use communal microwaves or fridges in offices, or their confidence to invite friends over to their house (due to fear of being bullied).

“White people are able to establish careers for being experts and authorities on the stuff that people of colour do on a daily basis”

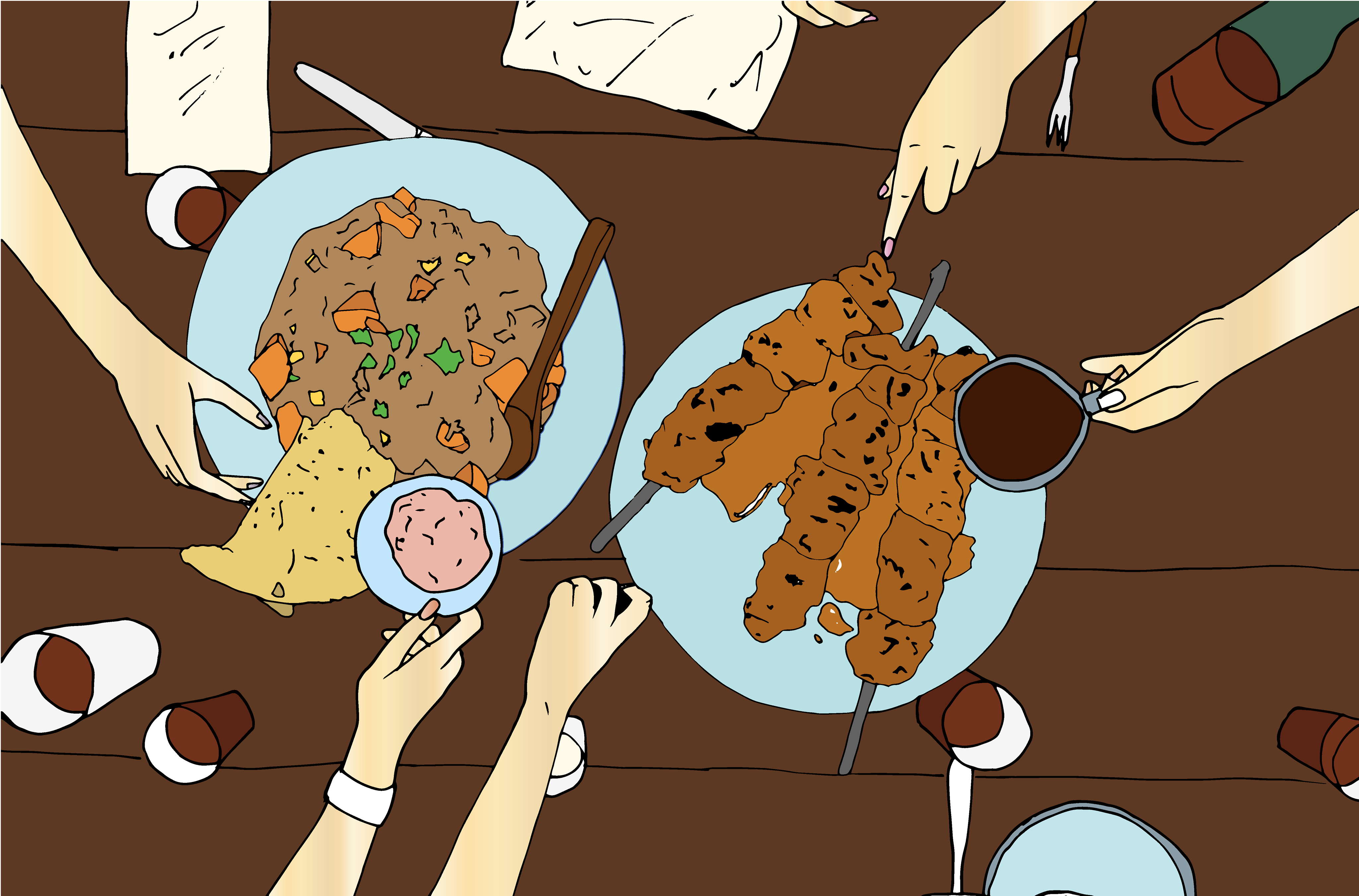

Yet, something has changed. Foods that have, in the past, been considered too flavourful, too smelly or too spicy for my white friends, are now in restaurants and in British homes nationwide. “Chai teas”, “Indian dhal soups”, “naan breads” and “chicken tikka masala curries” are popping up everywhere. In a way, the positive aspect about this trend is that I am becoming more comfortable with the food I grew up eating. As a growing number of supermarkets offer ingredients to cook “world food”, the weekly shop has become easier (however the costs of these ingredients are rising, making them inaccessible to many). But I would be lying if my teeth didn’t clench every time someone ordered a “chai tea” (a “tea tea”) or a naan bread (a “bread bread”’). It’s frustrating when your culture is commodified and appropriated as a trend.

This commodification of food, a phenomenon not unique to Indian food, isn’t just happening in large supermarkets or coffee chains, but is visible throughout the country. When I go to contemporary food markets such as Broadway Market, Camden Market or the Bath Christmas Market, I see at least one stall owned by a white person selling “ethnic” food. A couple of seconds into the conversations with these stall owners, they tend to inform me about their backpacking trip to some “third-world” country, where they were so inspired by the incredible culture and all the smiling faces of the natives that they decided to share this life-changing experience with others, by adding some coriander to a £8 bland curry for the sophisticated British palate. White people are able to establish careers for being experts and authorities on the stuff that people of colour do on a daily basis. It’s as though PoCs and our lives are objects to be observed and studied – rather than entire countries, cultures, and individual complex lives.

“As people’s complexities and oppression are reduced to their cuisine to satisfy the British palate, ethnicity becomes a spice that will liven up a dull, mainstream white dish”

In the few instances where I am not physically surrounded by appropriated food, I spend my time listening to my white friends talk about how they found a great recipe (usually written by a white chef) that made the cuisine either healthier or more palatable. The common assumption these recipes tend to share is that adding some “curry powder” (never really understood what this is), chutney and chilli to some slaw, or beetroot, or chicken makes it a healthier and more palatable Indian dish. This coded fancy talk about “elevating” or “making over” non-European cuisines, is a rhetoric that brings to mind the civilizing mission the British took on to justify violent takeovers of the countries from which the very same cuisines originates.

Something about the whole experience has left a bad taste in my mouth. The British people’s love for “Indian food” has gone so far that the Foreign Secretary Robin Cook named Chicken Tikka a British national dish in 2001, to highlight how the British adopt influences from other cultures. This commodification of “Otherness” through food has been so successful, because it offers an acceptable degree of contact with said “Other”. As people’s complexities and oppression are reduced to their cuisine to satisfy the British palate, ethnicity becomes a spice that will liven up a dull, mainstream white dish.

“This desire to be a true global foodie, that does not see colour, a consumer without borders, disconnects food from the communities it originates from”

What haunts me the most about this whole phenomenon is how communities in the West have learnt to love food from other cultures but not the people. Note the reduced access to welfare for ethnic minorities, increased barriers to access the NHS for migrants, tougher immigration rules that have split apart families, increased surveillance of PoCs as part of counter-terror strategies, increased the racial wage gap, and solidified segregation through social housing and gentrification.

When it comes to food, it seems that the existence of PoCs is only acknowledged to highlight how “authentic” a particular restaurant is. We live in a time where the discriminating British foodie has an ever-evolving list of essentials in their pantry: soy sauce, hummus, and “curry powder”. This begs the question: why are PoCs forgotten over and over again, while their food (as well as their vocabulary, music, art, hair, clothing) are consumed and adopted?

You may ask why am I being such a killjoy about people showing appreciation for another culture’s food. This desire to be a true global foodie, that does not see colour, a consumer without borders, disconnects food from the communities it originates from. Often, when these foodies go searching for authentic food, they aren’t referring to Italian, French or British cuisine. Usually, the search is for Indian, Ethiopian, Mexican, Thai or Vietnamese – food that belongs to people of colour. This suggests that white people are the authority and culture connoisseurs that discover good food.

I have no doubt that these people may genuinely love the food, but in that case they should just eat it. They shouldn’t expect a gold star for trying a new cuisine, or pretend that the culinary experience gave them an insight to our “exotic” ways or comment on how the food reminds them of the incredible trip they took to the “third world”. Just eat the food, and recognise that we have been eating this very food too, and our sustenance is not here for your amusement.