‘Everyone has a choice of what and who they become’ – The Problem with Not Seeing Colour

Paula Akpan

12 Oct 2015

While perusing my Facebook news feed a while back, I came across a meme posted by Brian Banks, an African-American NFL linebacker. The picture, taken in a court room, shows three black males: one in what appears to be the uniform of an offender, possibly a juvenile delinquent, while a suited legal practitioner stands next to him; behind them stands a police officer. The picture is captioned with the words ‘3 black men. 3 different positions. We all have choices.’ Banks simply wrote ‘#Powerful’ with the share.

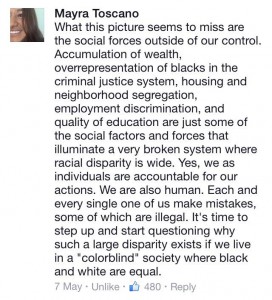

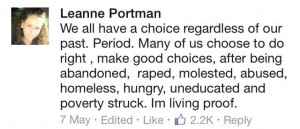

Some commented their disdain towards the picture, however, with over half a million likes, there was an overwhelming feeling that choices trump circumstances and that you must take responsibility for your actions, rather than make excuses. However, this shifts responsibility onto the black individual, rather than the system that they are born into.

Some commented their disdain towards the picture, however, with over half a million likes, there was an overwhelming feeling that choices trump circumstances and that you must take responsibility for your actions, rather than make excuses. However, this shifts responsibility onto the black individual, rather than the system that they are born into.

This viewpoint advocates that black people are free to fly as high as they want, while overlooking their clipped wings; although social mobility is by no means impossible, this ‘colour blind’ way of thinking overlooks the uphill struggle.

By highlighting the issue as one to be solely dealt with by the autonomous individual, it diminishes the possibility that it is the state who has failed these individuals. For example, it is easy to say that offenders made bad choices and committed illegal acts, thereby justifiably resulting in their incarceration.

However, that overlooks the greater social forces at play. For example, in autumn 2014, it was calculated that 47% of the prison population received no qualifications, as opposed to 15% of the working-age general population. While only 2% of the general population were taken into care as a child, this contrasted with 24% of the prison population (Prison Reform Trust, 2014). Correlation does not equate to causation and it cannot be conclusively stated that offenders are imprisoned because they had no GCSEs. However, such trends underline that there certainly is a higher proportion of the prisoner population hampered with negative social characteristics.

However, that overlooks the greater social forces at play. For example, in autumn 2014, it was calculated that 47% of the prison population received no qualifications, as opposed to 15% of the working-age general population. While only 2% of the general population were taken into care as a child, this contrasted with 24% of the prison population (Prison Reform Trust, 2014). Correlation does not equate to causation and it cannot be conclusively stated that offenders are imprisoned because they had no GCSEs. However, such trends underline that there certainly is a higher proportion of the prisoner population hampered with negative social characteristics.

Certain trends have also been spotted between race, the justice system and the labour market, with ‘a person from the black ethnic group six times more likely to be stopped and searched in 2011/12… than a person from a white ethnic group’ (MoJ, 2013). In addition, unemployment rates for black ethnic groups are three times higher than the unemployment rate for white ethnic groups (Race for Opportunity, 2014).

Despite some similarities in terms of social instability, the monumental difference between being black and being an offender is that, while offenders have some agency with regards to whether they choose to offend or not, a black individual has no influence over the race they are born into, any stereotypes that come attached with that race and whether or not individuals and institutions will mistreat them as a result.

The image itself is disheartening due to the assumptions that it makes. It assumes that because all of the men are black, they have all had the same starts in life; that they have all been granted to the same opportunities and where they have ended up is purely down to their own individual actions and willpower. However, it is entirely impossible to cast judgement over how it is that they achieved their various positions as we simply do not know. We don’t know their financial backgrounds, the kind of education they received if any, where they grew up – the list goes on. The fact that the meme appears to be based on assumptions about black men reduces the effectiveness of any positive message it may be seeking to promote.

We are all faced with choices and, while we have influence over how we handle them, it is naïve to presume that each individual has absolute control over their circumstances. Not only does it underestimate the power of societal and institutional forces but in the case of any kind of minority social group (race, gender, sexuality etc.), it denies the way in which history has shaped social relations and assumes that all have been born on equal footing without any disadvantages such as stigma and negative stereotypes. It denies the framework within which the worth, privilege and abilities of black people are constantly in question and promotes the idea that everyone is universally considered to be of equal worth.

By propagating the idea of absolute responsibility and choice, it overlooks the times in history when the power of social group was taken away and when the power of the normative majority was reinforced by the pillars of institutional powers such as the Jim Crow laws which legitimised the segregation of black and white people and the Local Government Act of 1986 which made it illegal to ‘intentionally promote homosexuality’.

Exclaiming that you do not see colour and that life is what you make it, is not being an ally. It is neither constructive nor understanding of the power of privilege and circumstance. One commenter on Banks’ picture asserts that we have a choice in how we respond to ‘unwanted life experiences’. However this term ‘unwanted life experiences’ cannot be applied to issue of discriminatory behaviour because it then assumes instances like racism and hate crimes violence to be normal and natural, though an unfortunate course of life.

Frankly, during a period of heightened racial tension within the West, we have reached a critical and most problematic point when members of society choose ‘colour-blindness’, ceasing to see institutionalised racism as an abuse of human rights and instead beginning to see it as just another unavoidable life process.

http://raceforopportunity.bitc.org.uk/Leadingchange/Factfile/Ethnicitylabourmarket

https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/statistics-on-race-and-the-criminal-justice-system-2012