Family Ties: the exhibition reminding us why we need to uncover, preserve, and retell our own stories

Rianna Croxford

15 Aug 2018

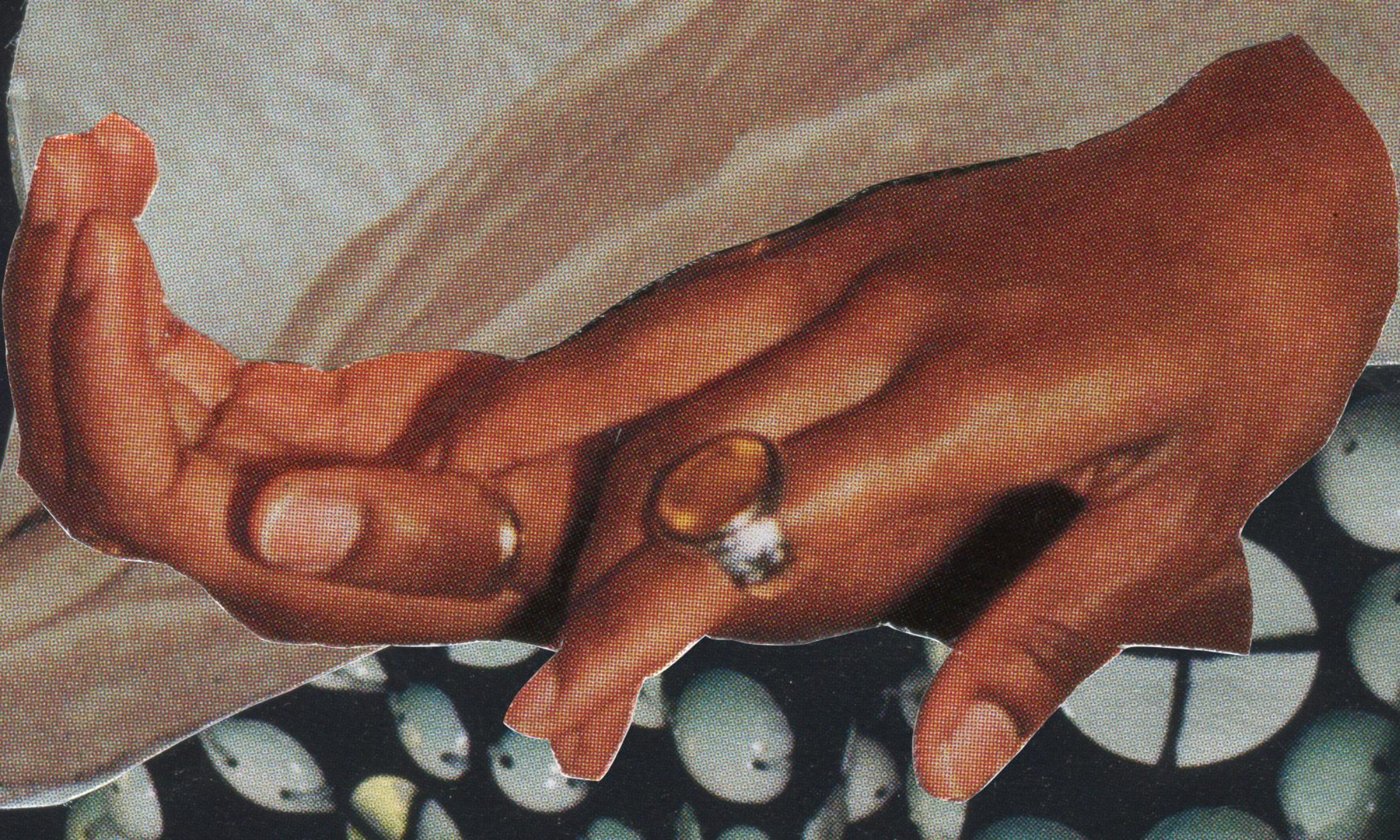

Black Cultural Archives: Family Ties

A bit like reading a book from the last page, our identities constantly gesture towards past narratives unknown to us. Few are so fortunate, however, to be handed a chapter of their own history directly on their doorstep.

When British spoken word artist Yao “Tuggstar” Togobo received a plastic bag full of mouldy papers at his home in east London, little did he know they contained the story of one of his ancestors – a Ghanaian king.

Scorched and decayed, the fragmented documents presented to him by his mother, Promise Adamah-Togobo, told the narrative of his great-grandfather Togbui Adamah II, an Eʋe Fia (king) who ruled the Some people in Ghana from 1915 until 1963.

Black Cultural Archives: Family Ties

Dating back as early as 1858, the papers revealed first-hand accounts of colonial everyday life in Ghana between 1900 and 1950 and chronicled major historical events including providing context to the 1884 Berlin Conference, in which the imperial European powers sought to legitimise the colonisation of Africa by formalising territorial rule and trade regulations.

Togbui Adamah II also details his own recollections of world war efforts, local resistance to British occupation, and how Ghana achieved independence on 6 March 1957 under their first president Kwame Nkrumah. Such alternative perspectives provide a necessary and valuable mode of resistance against the undeniably whitewashed and biased state of British history.

Black Cultural Archives: Family Ties

“Our parents and grandparents lived during some incredible times and the way they interacted with an exact period in history is at our fingertips,” the 39-year-old poet said. “I was literally communicating with an ancestor who had left a large enough footprint for me to know and understand him and his achievements.

“It’s a really eerie feeling that someone you are connected to is communicating to you from the dead through the documents they kept.”

Yao’s experience is a prime example of the magnitude of stories that can be uncovered through family ties. Inspired, he approached the Black Cultural Archives (BCA) to help restore the papers. It cost five years and a £21,000 grant from the National Manuscripts Conservation Trust and the Heritage Lottery Fund for BCA archivists to painstakingly salvage the Adamah family papers which had deteriorated under Ghana’s humid, tropical climate.

Black Cultural Archives: Family Ties

The BCA opened in 1981 as the UK’s first national black heritage centre and is located, on Windrush Square in Brixton. The aim of the heritage centre is to collect, preserve and celebrate the histories of African and Caribbean people in Britain.

“We want to tell a better story about the history of Britain, a history more diverse than what we think,” said BCA director Paul Reid, who has held his position since 2006. Born in Brixton to a Liverpudlian mother and a Jamaican father, he has close ties to the local community. “There’s always a sense that black history usually takes place overseas – Africa, the Americas, and the Caribbean – that we too often overlook our own stories here in Britain.”

He quotes an extract from the Adamah documents. “‘They came in the night, they brought alcohol, and in the morning three of our children were missing.’ It was like a line from Chinua Achebe’s Things Falls Apart,” Mr Reid added.

“It’s important that as black people we deliver these stories ourselves because a lot of the time we allow other people to tell our stories for us”

The Adamah papers are at the root of the Family Ties exhibition currently being showcased at the BCA. It opened in March on the day of Ghana’s independence and offers a rich insight into Eʋe culture, language and history.

Its curator, Natalie Fiawoo, found her own family history embedded in the 100-page document. She recognised the handwriting, and later signature, of her great-grandfather who had launched the first non-missionary school in the south-east of the Volta Region in Ghana. Yao Togobo’s maternal grandfather, Makavo Adamah, worked as a teacher under her great-grandfather’s school, which was in a building owned by his paternal grandfather Theophilus Togobo.

“It’s been a weird journey of coincidences that have put me as a part of the story,” Ms Fiawoo said.

It is Ms. Fiawoo’s first exhibition. As a Ghanaian-English woman breaking into the oversaturated white art world, she feels ownership of cultural stories is crucial. “It’s important that as black people we deliver these stories ourselves because a lot of the time we allow other people to tell our stories for us. Because you understand things differently when you’re a part of that people, of that community.

“A lot of the people who tell our stories don’t look like us,” she said.

Natalie Fiawoo – The Exhibition’s Curator

While personal archives of the African diaspora are hard to trace as a result of displacement and imperial subjugation, stories accessible closer to Britain are of as much value. It is important for the community to create and control the circulation of their own narratives because this has been historically denied. Rather, their stories were controlled and shaped through colonial propaganda and history books. This is why we need to start reclaiming past and present narratives by recording them ourselves.

So how does one go about this?

“Documents are the evidence base of history,” Mr Reid said. “Start with conversations with family – the stories that exist in the minds of people.” The process of verbal storytelling is reminiscent of traditional Eʋe practice whereby stories, ideas and arts are transmitted orally from generation to generation.

Black Cultural Archives: Family Ties

“There is a value in preserving the actual records, too,” Patricia Hamzahee, a BCA trustee, added. “Take the Windrush generation for example – those stories will be lost if we don’t move to record and preserve them now.”

Ms Hamzahee raised the important point that the stories which frequently circulate about black British communities are overwhelmingly negative. “The stories told about us are always about slavery and violence,” she said.

“We need to also celebrate the positive stories, the positive histories which counter this negativity.”

Mr Reid agreed: “It’s important that our children see themselves reflected back accurately or at least represented somewhere in a narrative they can identify with.”

This would help foster a stronger sense of identity among young people, he said. It is only by acknowledging their roots that black British youth can fully shape their present identities. Without this feeling of belonging and connectedness, it is easy to feel isolated.

“Take the Windrush generation for example – those stories will be lost if we don’t move to record and preserve them now”

“The grappling around identity is the sense of belonging, home, space, and place where they live and stay in contact with their roots,” Mr Reid explained. “Anyway, why does ‘home’ have to be singular?”

Leaving the BCA, I was filled with regret that I didn’t record the stories of my own great-grandmother who died in 2011 in Accra, Ghana at the grand age of 110 – or so she suspected, since she lost her birth documents in the 1890s. I had recently done a DNA test to help me answer that elusive question: “where are you really from?” My blood revealed roots in Ghana, Togo, Britain, Scandinavia, the Middle East and South Asia. Yet while I may never fully uncover my own history, I know I can, at the very least, start preserving my family’s current narrative.

The Family Ties exhibition runs at the Black Cultural Archives, Windrush Square, Brixton, SW2 1EF until 1 September 2018. Entry is free. For more details visit their website.