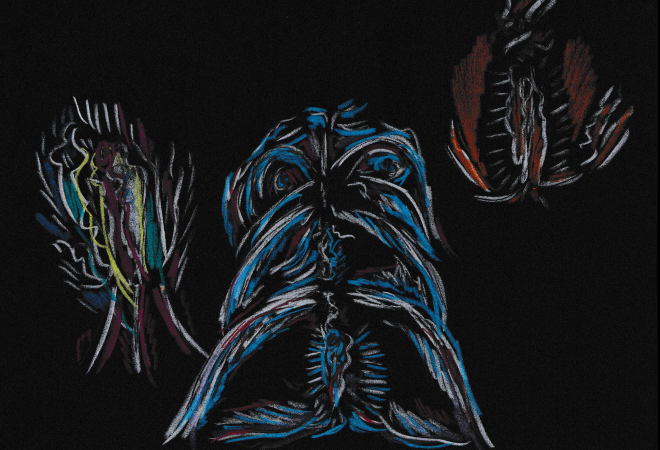

Harrowing, repulsive, insightful. A contrasting combination of words perhaps, yet the only ones I deemed suitable for describing the National Theatre of Scotland’s production, Rites, exploring Female Genital Mutilation (FGM). Directed by Corra Bisset, the production seeks to both educate on the dangers of FGM and spread awareness that it is still being practised in the UK today.

Despite being a widely practised cultural tradition, FGM has been sanctioned as taboo. This has contributed to the alienation of communities, which practise FGM, from mainstream Western society, as well as the practise being driven underground. These are both undesirable and counterproductive outcomes.

The production gives us a raw, unabashed insight into the different types of circumcision and the various rationales behind them. Rites traces the impact that deep-rooted cultural beliefs have on present day actions. All of this comes together in a whirlwind of accounts, sourced from women and girls who have been subject to enforced cutting and currently reside in the UK.

However, the most surprising aspect of the production was its non-accusatory approach. The topic was delicate and personal and the stories greatly varied. Some of the women didn’t even realise they had been circumcised until coming to the UK, where they learned about it in greater detail. Consequently, such realisation was accompanied with shock and shame, making their decision to reveal this to the world a massive feat. Therefore, it is significant that their stories were met with understanding and not hostility.

As an audience it would be easy to disassociate ourselves from these women and their experiences, creating a divide between us and ‘them’. One could regard the practice through a moralistic Western lens, discrediting it as complete savagery. However, FGM is a lot more complex than mere cutting; it is viewed by some cultures as a female’s ‘rite of passage’ and a necessary procedure in order for women to retain their purity. Rites recognises that, and although we may not agree with its religious and cultural connotations, we should acknowledge their existence in order to discern the best possible way of combatting it.

Thus, controversial as it may be, Rites shows us both sides of the coin. We are confronted with both a tearful Egyptian woman who recounts her experiences in explicit detail and a British Nigerian mother who wishes to send her daughter back to the capital to undergo the process and ‘save the girl’s honour’. Designated cutters discuss their prized position in society, while, in the same breath, midwives curse the painfully complicated births FGM leads to. A black American woman argues for its symbolic importance to both her and her community.

In the end, Rites raises the question of how much weight we should give to cultural relativism, where ethics are concerned. Of course, the medical cons of FGM and its disregard for the rights of women heavily outweigh its cultural value. However, the production’s ability to deviate from a narrow-minded portrayal of FGM and avoid the general labelling of the cultures practicing it as ‘barbaric’ makes for a refreshing change. Hopefully, this will go a long way towards inviting the communities affected by the practice into an open dialogue about the issue.

To find out more about FGM follow the link: http://www.fgmaware.org/