Rediscovering the African choir that toured Victorian Britain

Getty has released thousands of images of Black people for free in order to unearth our histories for a new generation.

Precious Adesina

09 Sep 2022

London Stereoscopic Company/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

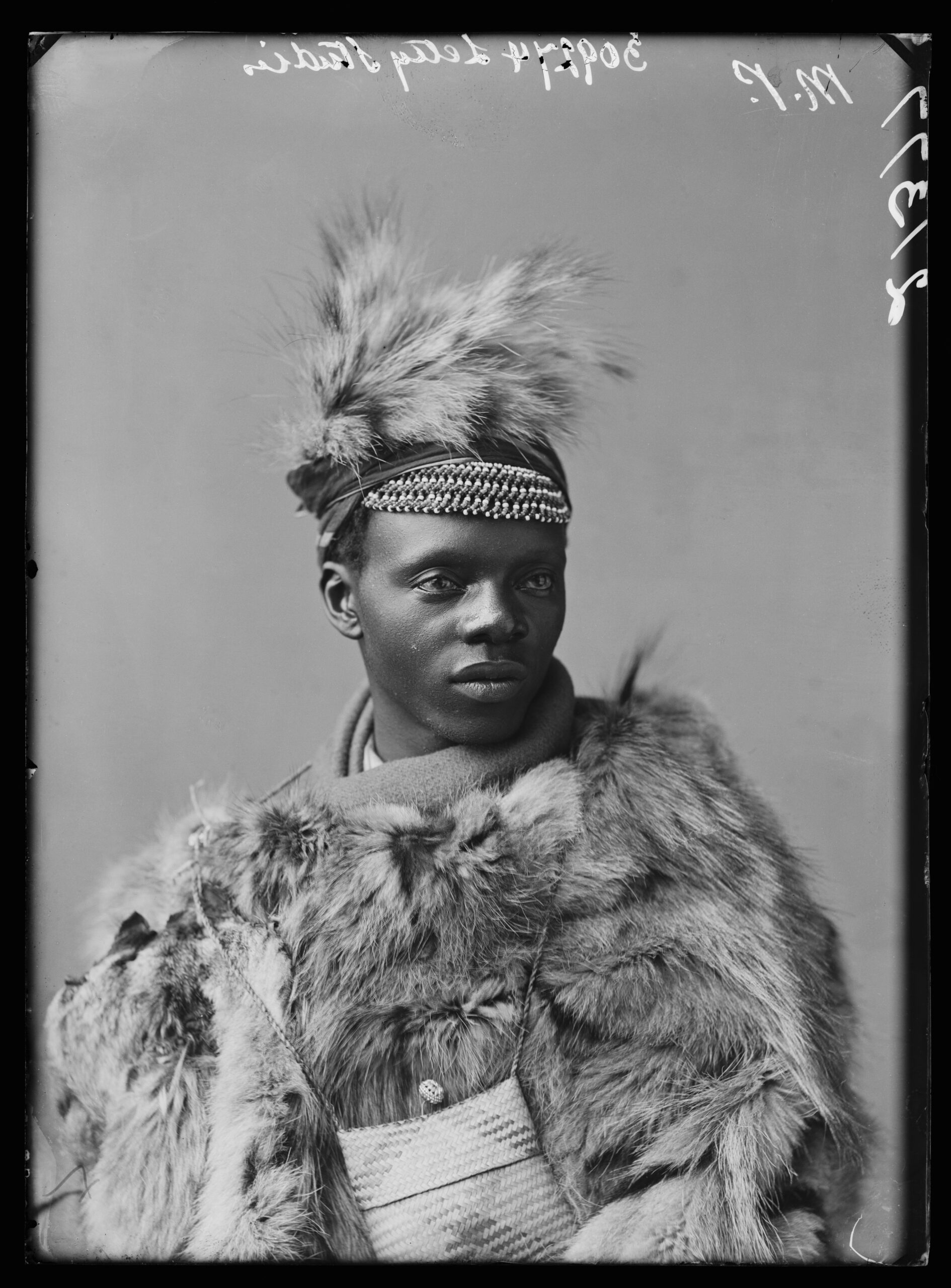

Between 1891 and 1893, members of The African Choir, a South African musical group, toured Britain to raise money for a technical college in their home country to support the growth of Black labour force. The choir performed “to great acclaim and large audiences at major venues and for Queen Victoria at Osborne House, [a royal residence in the Isle of Wight],” says Renée Mussai, the senior curator at Autograph. The art gallery in Shoreditch is renowned for championing photography that explores sociopolitical issues.

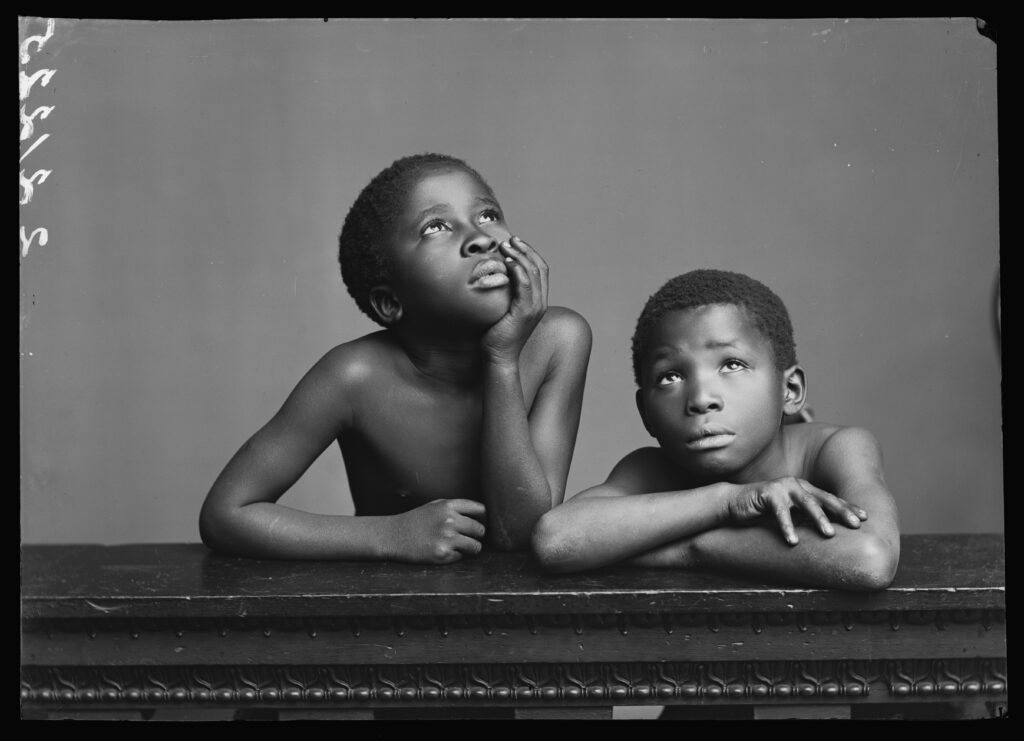

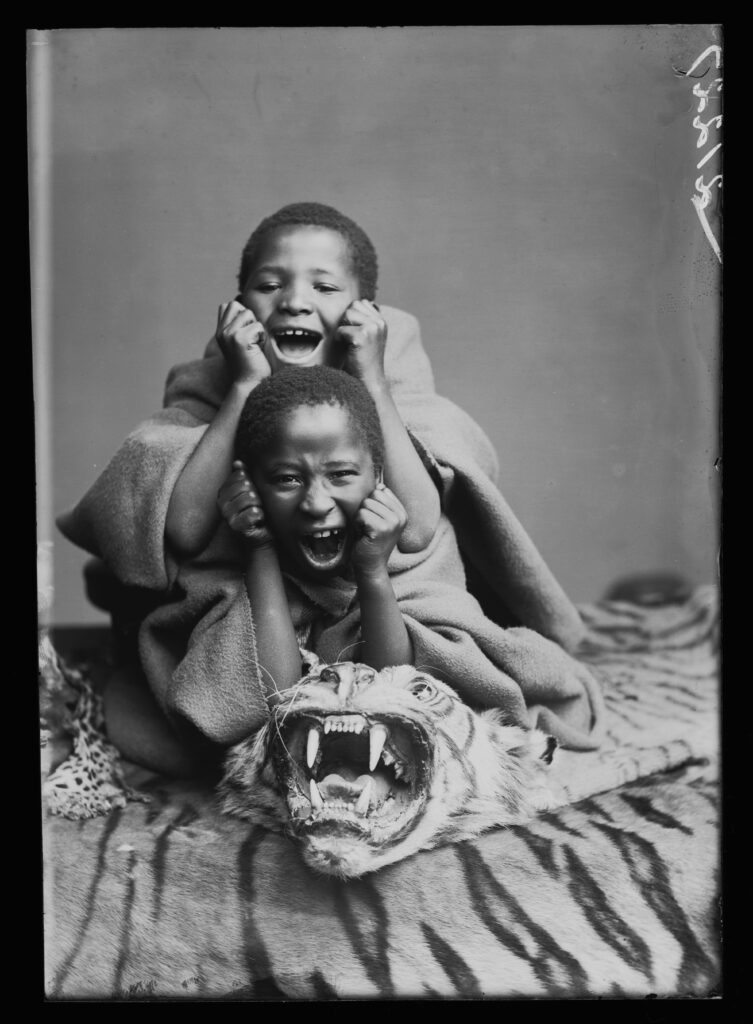

The choir had 16 members. There were seven women, seven men and two young choir boys, Albert Jonas and John Xiniwe. During this trip, portraits of the singers were made on glass plates, before the images were forgotten for over a century. These included vibrant images of the two young boys, Albert and John, both small and slim with short hair, often laughing with each other and playing with props in slacks and loose-fitting shirts.

“The set was shot by the London Stereoscopic Company, which was one of, if not the first-ever, commercial photographic agencies in the world – working much like Getty Images does today,” says Jennifer Jeffrey, senior archive editor at Getty Images, noting that “a plausible explanation” for the images of the choir not making it into history books is that they didn’t fit the unflattering narrative and stereotypes of Africans at time.

“Some members were graduates of Lovedale College’s Alice Campus,” she adds. Lovedale College is a missionary school in the Eastern Cape Provicence and, today, Alice is their most rural campus, focussing on agriculture. “It’s unclear who actually shot the set, but I feel it may have been Reinhold Thiele, a German staff photographer, who worked for LSC at that time.”

But, despite being mostly inaccessible for almost 130 years, these pictures can now be found online as part of Getty Images’ Black History and Culture Collection (BHCC), an initiative that provides free access to a curated selection of nearly 30,000 rare images of African and Black diaspora in the UK and US from the 19th century to today. Kwame Asiedu, project manager for BHCC, believes that if photos such as the ones in the archive were available to him as a young boy, it would have helped him find solutions to questions he had growing up about being a Black man in Britain. “Images are powerful,” he says. “I’m not saying my questions would’ve been answered, but these images would’ve allowed me to find some solace.”

What Kwame is most excited about today is how creatives and educators will use the BHCC to teach Black people about their history. “Without these photos, you wouldn’t be able to do certain projects. I used to teach in a Saturday school, and we would often end up in a situation where we’d see a photo, and we just couldn’t use them,” he says. “When you read why people want to use the collection, the projects they describe are wide and expansive.”

Photos of The African Choir are some of the earliest photographs in the BHCC. According to Renée, the images were unearthed at the Hulton Archive, a division of Getty widely considered to be one of the oldest and most extensive archives of all time. They were found in 2014 as part of Autograph’s The Missing Chapter: Black Chronicles – a research program, set of exhibitions and an upcoming book. The glass plate negatives were among several others and wrapped in parchment paper.

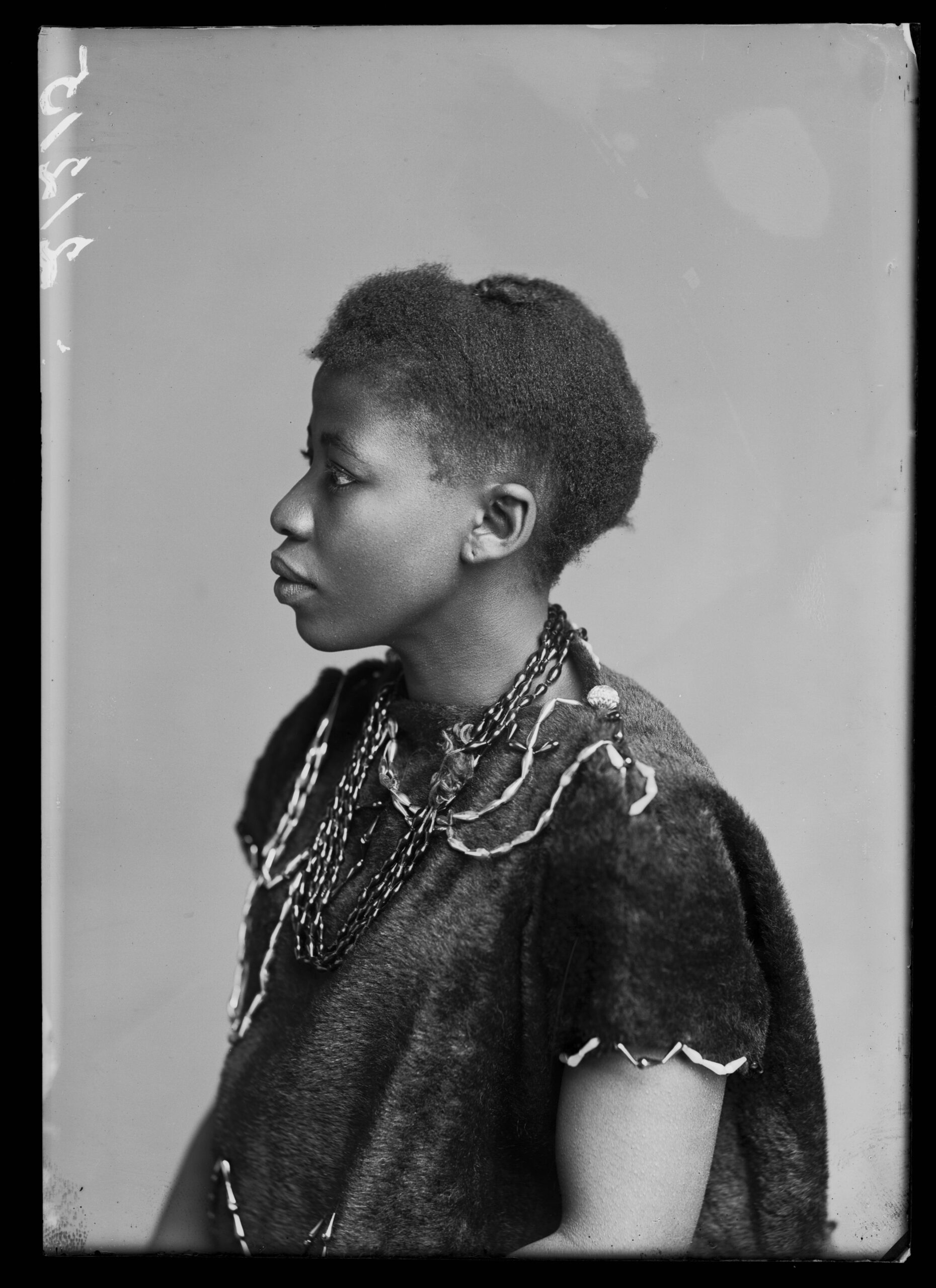

“This is one of the reasons why they look so ‘contemporary’,” Renée says. “It is incredibly rare to be able to print and digitise archival photographs from that era by working with the original plate materials, as opposed to the more familiar vintage, often faded sepia-toned prints.” Consequently, the photos could be reproduced in black and white to a high quality for Autograph’s Black Chronicles exhibitions. “The photography itself is remarkable, as are the sitters’ expressive faces –when looking closely, each detail is meticulously recorded, each pore on Eleanor Xiniwe’s beautiful skin is microscopically preserved, each crease in the cloth of her draped garment and headscarf recorded for prosperity.” Eleanor was the wife of Paul Xiniwe, the most senior member of The African Choir and a member herself.

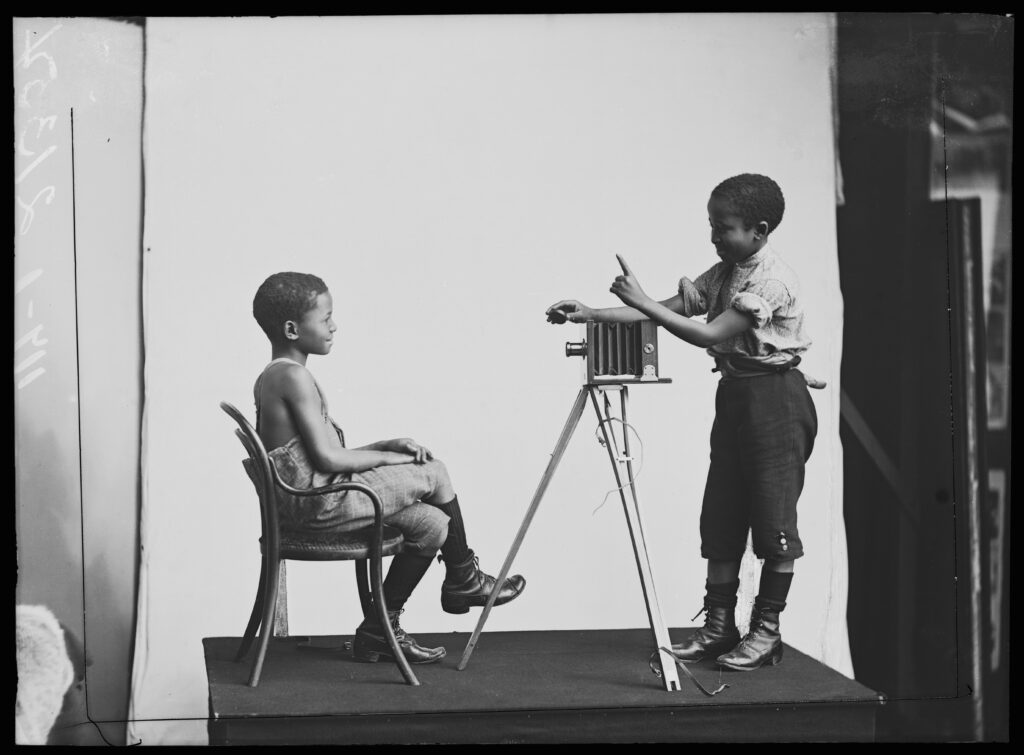

What also makes these images stand out today is how the singers are represented. According to Renée, while the portraits do conform to some conventions and stereotypes of the time, both in terms of Victorian studio portraiture and in representations of Black figures, “they also disrupt those ideas,” as seen in the photos of Albert and John.

In one particular image, one of the boys sits in front of a large camera as if posing for a photograph. At the same time, the other stands behind the camera as if taking a picture. Renée believes the image opens up a “wonderful and deeply contemporary, urgent conversation on agency, subjectivity, performativity and self-representation.”

According to research, the photos were created “as promotional imagery to advertise the choir’s tour,” Renée says, which she notes the national media shared with the public as singers dressed in ‘native costume’. “It was important to include the contrasting images of the individual members of the choir both garbed in what the managers’ and probably what the white audiences thought of as the expected ‘exotic’ outfits, but also in ‘alternative’ clothing which again was probably forced upon them to engage the audiences at that time,” archive editor Jennifer adds.

Fittingly, what they wore in these images also highlights the nature of their performances. Their shows were divided into two halves. In the first part of the show, they performed African folk songs and compositions by South African musicians, the second, Christian hymns in English.

“The transition between the two acts was signalled by a change of costume – from ‘indigenous’ African dress to ‘local’ Victorian attire,” Renée says. “A transformation sartorially and musically orchestrated to illustrate a generative journey from ’native’ to ‘civilised’ which was a common trope in popular nineteenth century ‘exotic’ entertainment.”

However uncomfortable these little problematic details may be by modern standards, they highlight a widely unknown and multifaceted part of Black British history during the Victorian era. One that at first glance looks as if it could have been made today. “They feel as though they ‘belong’ simultaneously to both the present and the past,” Renée says.

The forthcoming Autograph book Black Chronicles edited by Renée Mussai will be published in 2023. Getty Images’s Black History & Culture Collection is available to view online.

This article was amended on 9 September to state Jennifer Jeffrey’s name. An earlier version mistakenly spelled it as Jennifer Jefferies.

Our groundbreaking journalism relies on the crucial support of a community of gal-dem members. We would not be able to continue to hold truth to power in this industry without them, and you can support us from £5 per month – less than a weekly coffee. Our members get exclusive access to events, discounts from independent brands, newsletters from our editors, quarterly gifts, print magazines, and so much more!