Growing up with a schizophrenic mother: doctors, detainment, and dealing with her death

Suchandrika Chakrabarti

16 May 2019

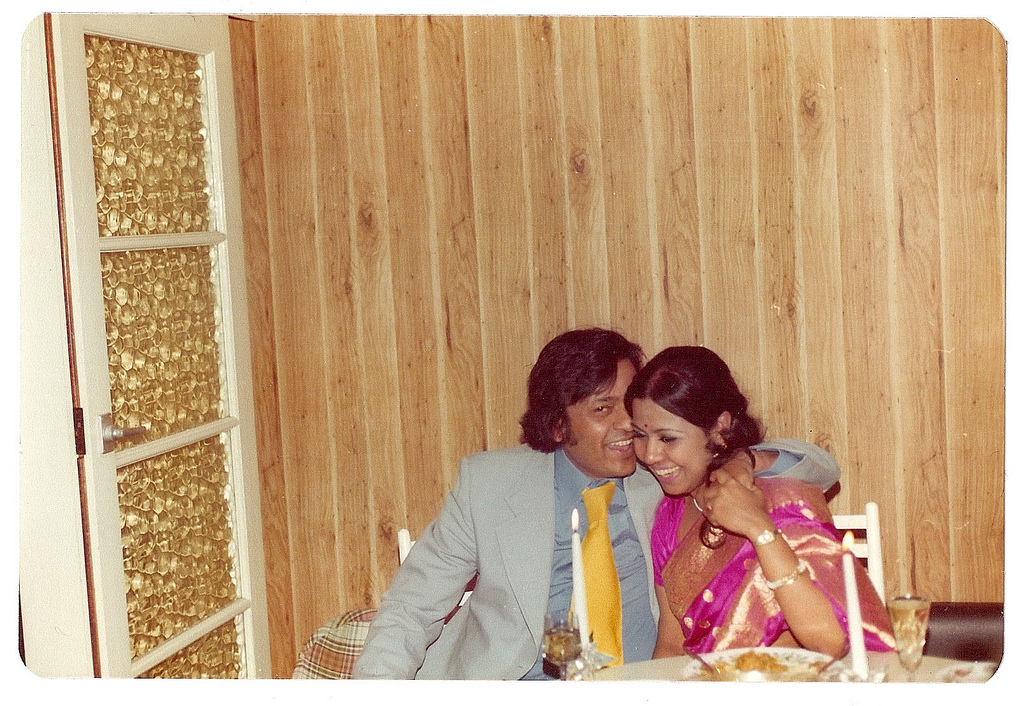

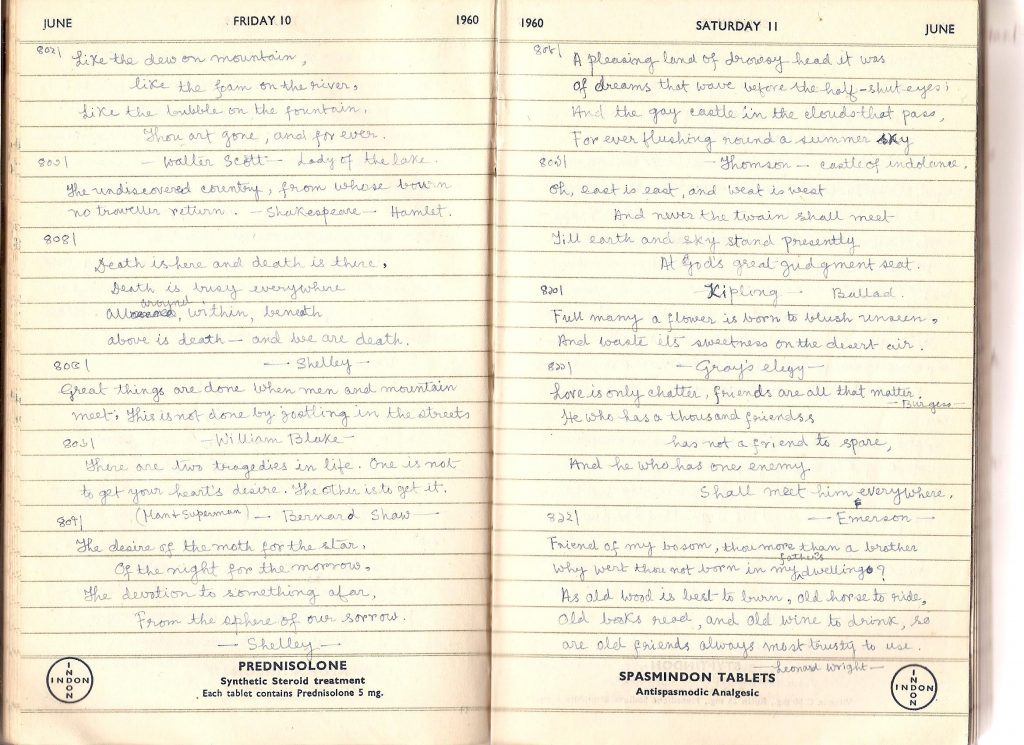

All photography by Suchandrika Chakrabarti

My birthday’s in late April, when the trees are in full pink bloom, a moment my mum used to call “the most hopeful time of year”. There is a blossoming tree opposite the house I grew up in, under which she would hold me for birthday portraits through my childhood. I wish I could find those photos. Each year, when the blossom first appears on the trees in London, I smile and think of her.

She will have been dead for 20 years next January. My mum died as a result of the brutal side effects she suffered after being treated with the drug clozapine, which is given to patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia. That means that my mum wouldn’t reliably take her medication, so she had to be injected with this drug.

Clozapine can deplete white blood cells, so patients are given blood tests to monitor this. My mum possibly refused blood tests, most likely developed a dangerously low white blood cell count which decimated her immune system in the way that chemotherapy does, and caught pneumonia. She died at home, at the age of 52. It was a Saturday morning and I was 16 years old, dressed in the uniform for my Saturday job at the Romford Woolworths.

“I would come home from school to her insistence that my bag was bugged, or to see her having an argument with the living room wall. While these moments were scary, they made me feel sorry for her too, and protective of her”

Writing that paragraph above feels like such a release. I’ve said those facts to very few people in my life, because I haven’t known how to lose the veil of shame and pain that I’ve always felt to be wrapped around that word, around her condition. I’ve decided to write this piece for Mental Health Awareness Week because I’m glad that we have come such a long way in the last two decades, and sharing our stories online has a lot to do with that.

I was lucky that my dad, a doctor, explained her illness to me from as early as I can remember, making it clear that her unpredictable behaviour was a condition, and not who she really was. Without a doctor’s insight, and without the internet, living in a house where someone has schizophrenia must feel like total chaos. On more than one occasion, I came home from school to her insistence that my bag was bugged and needed to be checked by her; or to see her having an argument with the living room wall. While these moments were scary, they made me feel sorry for her too, and protective of her. Whatever these unseen forces were, she felt threatened by them.

It’s still incredible to me how my mum’s chronic, at times severe, mental illness was not spoken about in the Indian community they socialised within, centred around the north and east boroughs of London. I recently went back home for a wedding, and my parents’ friends would talk to me about my dad (who died in 2003), but no one mentioned my mum. She was the friend, granddaughter, daughter, sister, wife and eventually mother of a doctor (although she didn’t live to see my brother get into medical school), but she was only diagnosed with the schizophrenia that she’d most likely had her entire adult life at the age of 51. Symptoms usually start to show between 15 and 25 years of age.

I could blame my dad for delaying her diagnosis, but I don’t; for him, it was like Sophie’s Choice: subject his wife and children to the potential devastation of her being sectioned? Deprive his children of their mother for treatment that might not even work? Or get through the latest “episode” and hope that the next period of normal (and funny and kind and intelligent and loving) behaviour would last? That’s the cruelty of a cyclical condition; it leaves you too much space to hope.

Government statistics show that black people were the most likely to have been detained under the Mental Health Act (sectioned) in 2017/18, and white people were the least likely to have been detained. Look closer at the breakdown of ethnic groups, though, and Indian people actually have a lower rate of detention than white British people, the second lowest of all the groups (with Chinese being the lowest). According to the Mental Health Foundation, the statistics on the numbers of Asian people in the UK with mental health problems are inconsistent, although it has been suggested that mental health problems are often unrecognised or not diagnosed in this ethnic group.

Those figures are recent; this article from July 2000, half a year after my mum died, says “African-Caribbean people are six times more likely than whites to be diagnosed as schizophrenic, but research shows this is nothing to do with biology.” So it seems likely that the reasons for the extremely varied rates of schizophrenia diagnosis across different groups has much more to do with stereotypes, spanning race, class, physical appearance, and many other factors. My mum simply didn’t fit the general idea of a schizophrenic person; she was a petite, assimilated Indian lady with postgraduate degrees who spoke perfect English, alongside a number of languages. She wasn’t physically “intimidating” and she’d never harmed or attacked anyone. This, too, delayed her diagnosis.

When it came, though, I thought my world would fall apart. One evening when I was 15, some doctors came to our house to assess my mum. They were the ones who decided to section her, to observe how she reacted to treatment. They took her away that evening. I remember my dad telling me afterwards, they’d said how well she’d presented, so perfectly dressed and well-mannered, even welcoming. Yet, they could tell so quickly that she had schizophrenia that needed urgent treatment.

I tried to comfort myself by imagining that the situation was somehow positive. It meant that she was getting the help she needed. Maybe she would be cured. I held onto that child’s hope and carried it like a shield on each painful walk through the multiple locked doors of the psychiatric ward where she was held under section. She would press a note into my hand at the end of each visit, thanking me for bringing in her clothes and other personal things, written in a suddenly shaky script that was evidence of her treatment’s horrible side-effects.

“My mum didn’t fit the stereotype of a schizophrenic person; she was a petite, assimilated Indian lady with postgraduate degrees who spoke perfect English”

Every time I left that place, I tried to push it all out of my mind, pretend it hadn’t happened. For over a decade, I told absolutely no one about my mum being sectioned three times. Whenever she came home, she failed to take her medication, because she didn’t believe that she had an illness. The strongest version of that treatment eventually led to her death.

Mental health and ill-health do not always show themselves in real life the way they do in films, TV, books, crime stories. Those false portrayals may well have wrongly shaped who we think is obviously mentally ill and in need of treatment. In a digital age, we have so many more tools to help us share real experiences of mental illness with other people who understand, have lived with it or near it. This gives me hope.

As a teenager in 1960s Calcutta, before the schizophrenia fully developed, my mum wrote some of her favourite lines of literature out in notebooks.

I do a similar thing by emailing myself. One of the couplets she noted down is from Gray’s Elegy: “Full many a flower is born to blush unseen, / And waste its sweetness on the desert air.”

It’s a poignant image that we both loved: a life so full of promise, but just existing in the wrong time and place. Still, no matter how sad her story, I won’t let her be reduced to that; for me, she’ll always be springtime and blossom and hopefulness.