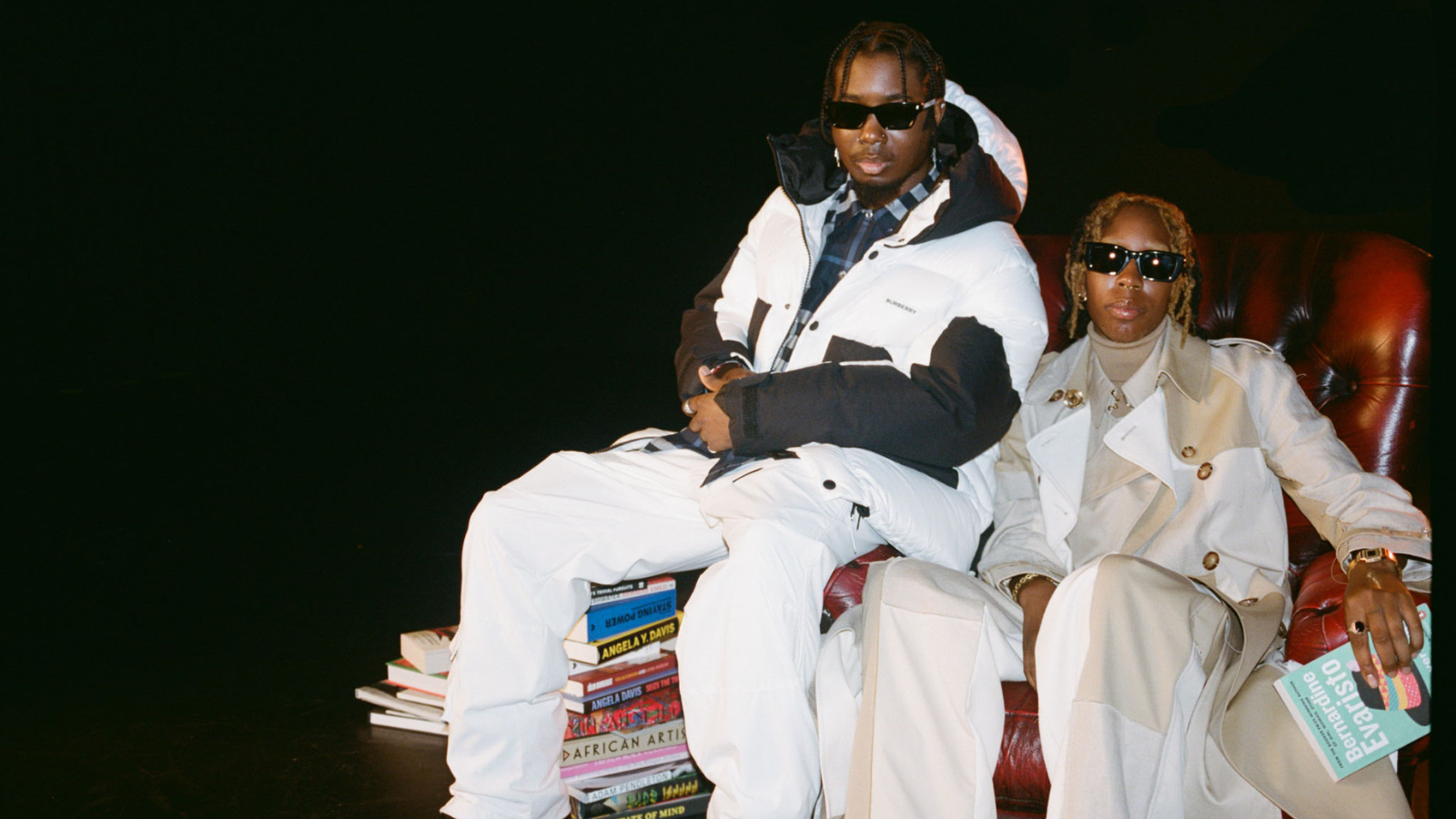

How a stained glass window in Clapham led me to the Krio people of Sierra Leone

Niellah Arboine

31 Oct 2019

Photography by Niellah Arboine

This Black History Month, gal-dem editors have explored the areas in which they grew up to unveil hidden histories close to their hearts.

Black people rarely appear in religious iconography in the UK. I’d always thought of myself as an observant person, but staring up at the detailed triptych stained glass window in the church I grew up in, I notice something new.

Among the luminescent god-fearing people frozen in time, stand three black people. One is a woman on her knees in front of abolitionist William Wilberforce, accompanied by the words from Deuteronomy 30:3: “Lord thy God will turn Captivity and have compassion upon thee”. It speaks to the unique history of the church. In the 19th century, the congregation was partially responsible for a pivotal point of black British history after slavery, which sought to figure out where we belong.

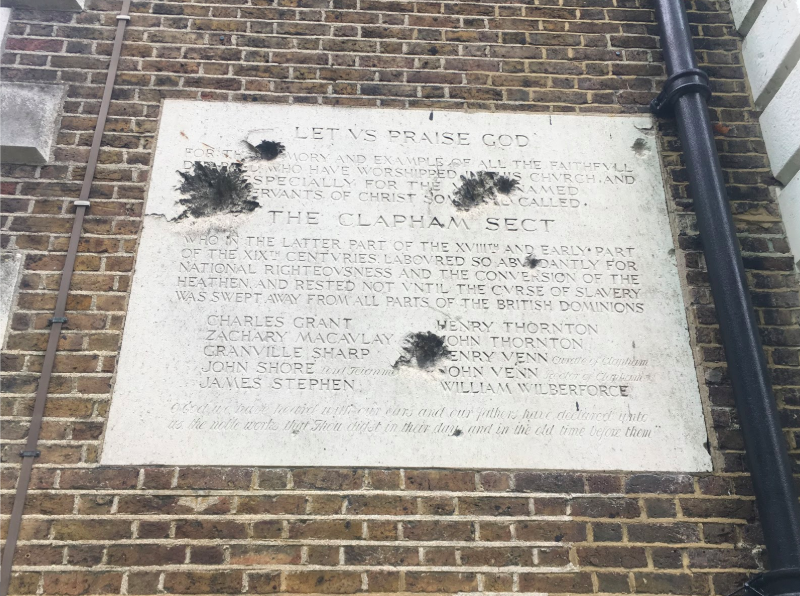

I grew up in Lambeth, South West London, attending Macaulay Primary School, a Church of England school in Clapham. Like most Christian schools, ours was attached to a local church – Holy Trinity. While these days Clapham is a sea of yoga yummy mummies and artisanal pet grooming shops, all situated around a giant green common, beneath this exterior belies a complex history. The Clapham Sect, a group of religious philanthropists and anti-slavery activists, most active between 1790 to 1830, worshipped here. They included in their ranks William Wilberforce, a politician, Zachary Macaulay, the governor of Sierra Leone, and John Venn (the creator of the Venn diagram). All three, and many more were involved in abolishing the slave trade – alongside less celebrated but incredibly important black abolitionists such as Olaudah Equiano and Mary Prince.

Today, visiting the church with my mum, however, my aim is to explore a specific project that the Clapham Sect was involved in. Because abolitionists didn’t just want to end slavery – they also wanted to return freed enslaved and displaced black people to Africa as compensation. Predictably this also tied into a desire to export “Christianity and civilisation”. The Sect also set up a school in Clapham, the African Academy, for children from Sierra Leone to educate the kids then send them back.

After visiting Holy Trinity church, I take a five-minute walk down to Clapham Oldtown, to St Paul’s church. It’s a strange feeling, walking the familiar streets of my childhood, now uncovering a history so unfamiliar to me. Just outside the gates, at number eight, is Zachary Macaulay’s former home, which also served as the premises of the African Academy. Here, 24 children arrived to learn with the Sect, and while some of them returned to Sierra Leone – like John Macaulay Wilson, son of King George, chief of Kaffu Bullom – some of the students died in the UK because they were unable to acclimatise. St Paul’s is where the children are said to be buried. Yet in the small graveyard next to the church, dotted with worn, lichen-encrusted headstones, I fail to find their graves. Their headstones have most likely been removed if they were ever there at all. I feel a great sense of sorrow for these black children uprooted from their lives, albeit for education, and left without even a headstone to memorialise their time in Clapham.

I’ve often contemplated the idea of returning “home” to the motherland. But, for some reason, I didn’t think this was a conversation happening 200 years ago in Clapham.

I can’t get into number eight, but I do visit a house a few doors down, belonging to artist and family friend Ruth Dupre, who created a documentary about the school, called Childsong. Although her house has a modern interior, my mind slips away imagining these black children dressed in Georgian clothes trying their best to fit into a society so far from home. As someone from the African diaspora, via the Carribean, I’ve often contemplated the idea of returning “home” to the motherland and pan-Africanism. But, for some reason, I didn’t think this was a conversation happening 200 years ago in my neighbourhood.

As the creation of the African Academy shows, where the “liberated Africans” were to live and how they were to be supported, was a great concern to abolitionists. At their behest, in 1787, Sierra Leone became a settlement for formerly enslaved people, black Londoners, and black people who fought for Britain in the American War of Independence after they were sent by the British. They became known as the Krios and their descendants live on in the country, and in the UK. Idris Elba is Krio on his paternal side.

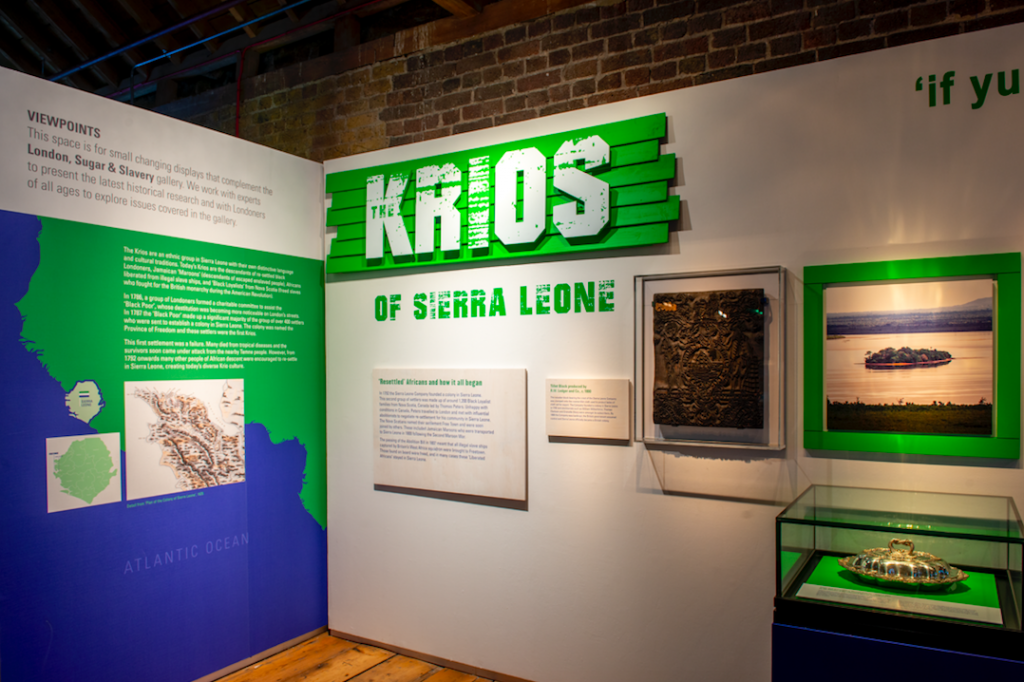

Fascinated by the Krios, my visit to the gloomy graveyard inspired me to go to a new exhibition at the London Museum Docklands, called The Krios of Sierra Leone. I meet with co-curators Melissa Bennett and Iyamide Thomas to look around. Having never been to the Museum Of London before, I was surprised, if not a little uncomfortable at the great (and necessary) detail of the transatlantic slave trade. Although their exhibition is small, it’s packed full of art and culture which recognises the legacy of the Krio people.

It’s been drummed home throughout my life that black people existed in the UK far before Windrush, yet it’s still felt validating to hear the experiences of black Londoners some two centuries ago. After Britain lost the war of independence, the enslaved people that fought for them who had been offered freedom couldn’t stay in the US and many ended up in London. They were promised pensions and charitable aid, but very few got the support they needed. These broken promises eerily don’t sound too dissimilar to the recent mistreatment of black people by the British government. “They ended up destitute and living on the streets,” Melissa explains. In 1786, a committee made up of abolitionists (like the ones from Holy Trinity) decided to resettle 400 poor black people to Sierra Leone. And it wasn’t just them, “there were also a few white women who had married these men, a few mixed-race children.” she explains.

Whether this was actually a positive idea is complex. On one hand, trying to find a home for those who were displaced and forced into slavery theoretically makes sense to me, but of course, it was white men choosing their fate, and probably for ulterior motives. Also, this British-backed mass migration probably didn’t take into account the needs or concerns of the indigenous people. But regardless of how the Krio people came to be, it still created a rich culture.

The Krios were more likely to receive an education because they lived in Freetown hinting at social divides. The Female Institution in Freetown, now called the Annie Walsh Memorial School, is said to be the oldest girls school in Sub-Saharan Africa. Sara Forbes Bonetta, a young girl of Yoruba descent who was rescued by a captain of the Royal Navy and taken to Queen Victoria as a goddaughter, even attended there.

“With some Krios, there’s some elitism,” Iyamide co-curator of the exhibition tells me, “because some have gone to the West. There are some people who are very anti-Krio.” she explains. “If you look at newspapers from Sierra Leone from the 1850s you’ll see Krio people referring to the other Africans as “natives,” says Melissa. “The British had fuelled that,” Iyamide adds. But the Krio people were the minority in Sierra Leone. When I imagine all these groups from the African diaspora figuring out how to live side by side, all I can think of is the Thai saying: “same same, but different.”

I think the traditional Krio dress, one of which is exhibited in the museum, sums up a lot of their history. “It was made by my sister in law, by the way in Freetown,” Iyamide tells me. The beautiful gown is fresh green covered in ornate deep purple onions. In fact, it looks vaguely familiar to me – like something I’d seen in Jamaica before, but with a distinctly European shape and undeniably west African influence. “It’s a mix of the liberating Africans, the maroons, the Nova Scotians” with Yoruba and Twi influence in there too.

After falling down a wormhole after being inquisitive about the people who embellish my local church, what I really learned is that black people don’t stop moving. We’ve been displaced, rehomed, taken, returned. Sometimes, that’s our own decision and sometimes the powers that be make the decision for you, like the children of the African Academy – some of whom would never return to Sierra Leone. But through looking at those journeys we learn so much more about our resilience which is a crucial takeaway from Black History Month.