How Britain’s exported homophobia continues to drive health inequalities amongst LGBTQI communities

Annabel Sowemimo

15 Apr 2019

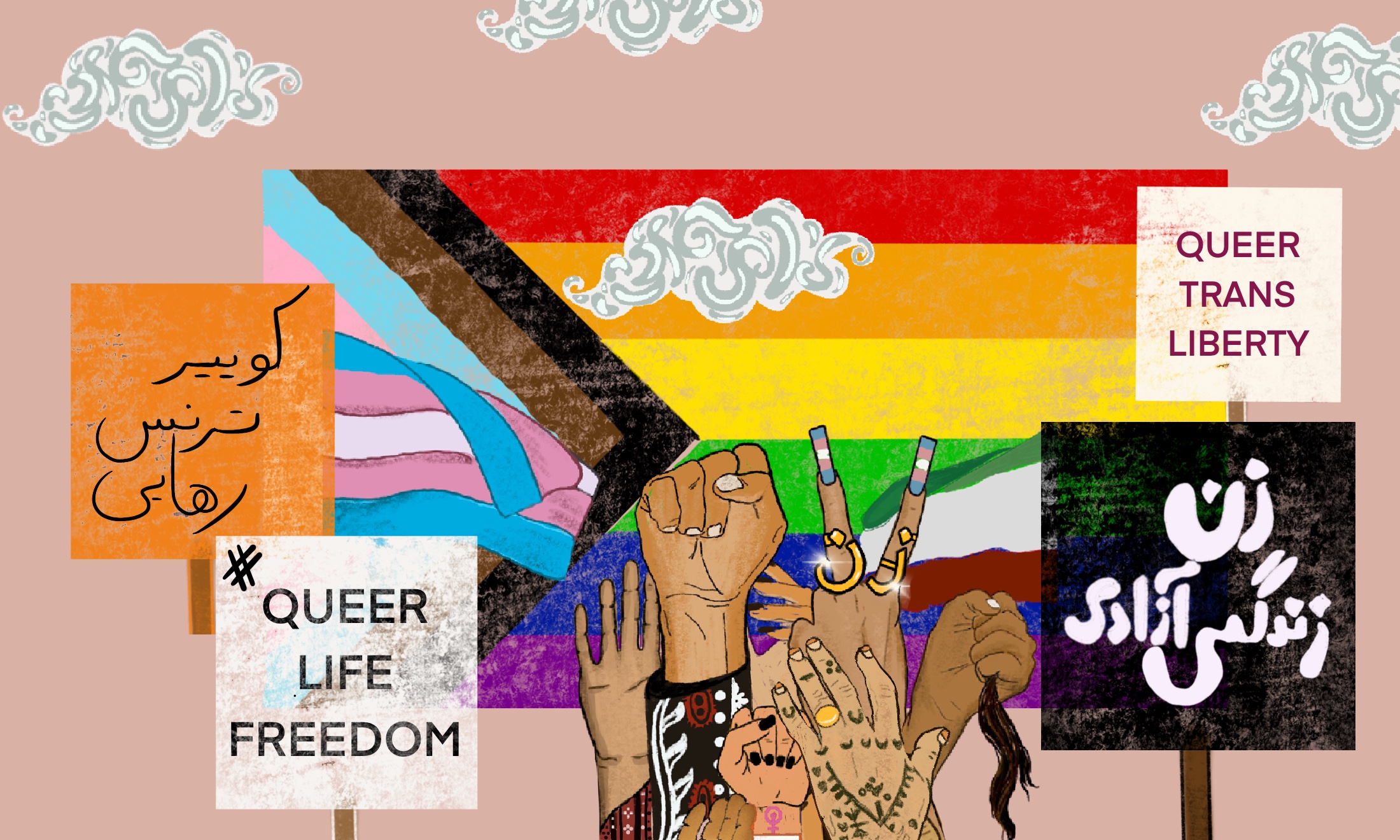

Illustration by Parys Gardner

It is a great shame to see black and brown faces on TV and in the newspapers being used as the face of homophobia and bigotry; denying their children (who may well be LGBTQI+ themselves) the opportunity to learn about LGBTQI+ rights. It is even more of a shame when you consider that LGBTQI+ people of colour have some of the worst sexual and reproductive health (SRH) outcomes globally, partly driven by stigma within our own communities. The greatest sadness of all is when you know homophobia in these communities is part of a colonial legacy; an awful reminiscence which we are still struggling to eradicate.

As Britain positions itself as a beacon of progress, from creating mandatory inclusive sex and relationship education to DFID championing LGBTQI+ rights abroad, it is essential we remember the colonial legacy that our country and other colonisers had in exporting homophobia. Same sex relationships are still criminalised in 72 countries, and, of these, 33 are in sub-Saharan Africa. Some of them still rely on penal codes (code of laws) introduced by British colonisers centuries ago. The introduction of penal codes prohibiting homosexuality

In Uganda, where the LGBTQI+ community suffer some of the worst acts of discrimination, the first penal code acts against homosexuality were introduced in 1950, referring to homosexuality as “unnatural offences” or “indecent practices”. In 2000, this act was revised to include same sex relationships between women and in 2014 attempts were made to introduce the death penalty for serial offenders, HIV positive people who engage in same sex relationships and people that perform same-sex acts with those under 18. Amnesty International reports that of 2018, Ugandans engaging in same sex relationships can receive a sentence of life imprisonment.

“Same sex relationships are still criminalised in 72 countries, and, of these, 33 are in sub-Saharan Africa”

Pre-colonial history demonstrates that prior to Christian missionaries’ arrival, same-gender relationships existed. King Mwanga, a ruler of Buganda in 1884 to 1897 had bisexual relationships; commonly engaging in intimate relationships with his male royal pages. When his pages converted to Christianity and started to refuse his advances, he ordered their execution. This series of events is still celebrated by some Christian Ugandans today, despite a continued claim that homosexuality is a Western import. Due to the continued stigma and discrimination faced by the LGBTQI+ community living in Uganda, it is very difficult to research the impact on SRH. However, films like the Pearl of Africa, released in 2016, which chronicles the story of a Ugandan trans women Cleo and her partner, show how increased secrecy prevents them accessing care and even food.

In India, Section 377 of the India Penal Code was introduced in 1861 by Britain colonialist outlawing “sodomy”, based on Britain’s Tudor 1563 “Buggery Act”. In 2014, India’s Supreme Court unanimously ruled to decriminalise homosexuality after LGBTQI+ groups campaigned and lobbied the government. Within Hindu mythology, there are depictions of deities changing gender and having homoerotic encounters. Whilst meaning is difficult to interpret, it demonstrates the historical presence of these communities.

Historically, the Hijra (otherwise referred to as “enuchs”, intersex, non-binary and trans) community in South Asia were revered due to their loyalty demonstrated to Lord Rama and had the ability to bring both good and bad luck. Following the introduction on anti-sodomy laws, the fate of Hijra across South Asia has changed substantially. Today, the Hijra community in many parts of South Asia continue to have their own sub-culture, however, they face extreme discrimination. Some are forced into sex work due to poverty; and lack of education and a risk of violence means that they often struggle to negotiate condom use – this has in turn fuelled an epidemic of STIs and HIV.

In Britain’s former Caribbean colonies many still possess laws derived from the Buggery Act with harsh penalties for “sodomy” – Trinidad and Tobago has one of the harshest penalties in the region with a maximum of 25 years in prison. In some former colonies such as Jamaica, Dominica, Guyana there is an extensive history of unchecked violence against the LGBTQI+ community – with Time magazine once referring to Jamaica as “the most homophobic country on earth”. Despite several LGBTQI+ groups campaigning to change this label, a 2019 report highlighted the case of two Jamaicans identifying as LGBTQI+ that experienced violence leading them to claim successful asylum abroad. The stigma and discrimination faced in such setting makes the work of NGOs aiming to target the spread of STIs and HIV amongst those forced into the shadows even more challenging.

Amongst my own Nigerian community, I see homophobia thriving – fuelled by Evangelical Christianity in the south and Islamic fundamentalism in the north. In 2014, then-President Goodluck Jonathan amended the British colonial code, turning same-sex relationships from a felony to a crime which carries a penalty of up to 14 years in prison. Human Rights Watch has reported the subsequent effects have been increased discrimination and harassment when LGBTQI+ people attempt access HIV care.

It was a relief when the book She Called me a Woman: Nigeria’s Queer Women Speak was released in 2016 and I got to hear the stories of queer women continuing to live their lives despite extreme measures to silence them. In 1987, Ifi Amadiume, a Nigerian anthropologist, demonstrated in her ethnography Male Daughters, Female Husbands the rich tapestry of gender relations and sexuality that existed amongst the Nnobi Igbo community pre-colonially, forcing people at the time to reconsider the history of gender relationships within Igbo culture.

“Amongst my own Nigerian community, I see homophobia thriving – fuelled by Evangelical Christianity in the south and Islamic fundamentalism in the north”

Subsequent ethnographies worldwide have unearthed a multiplicity of gender constructions, from the Vezo fishing people in Western Madagascar who formulate gender through societal roles, creating a “third gender”, sarin’ampela, to the “Two Spirit” Native American community.

Lastly, it is vital we acknowledge that science and medicine has been complicit in the oppression of LGBTQI+ communities (despite doctors like myself doing work to reduce health disparities). Early colonisers based penal codes on early scientific teachings on the mechanisms of biological reproduction and today eugenicists continue their quest for a “gay gene”, as if LGBTQI+ people need to be cured. Why are some in the scientific community not looking for a “heterosexual gene” and what is the exact plan if we do find genes that code for sexuality?

The gender binary and heteronormative relationships are a falsehood that continues to be reinforced despite a plethora of evidence to the contrary. The greatest shame of all is that many people still do not know their own history. I hear those from former colonised countries proclaim “homosexuality is a Western thing”, when in fact it is homophobia that is the true colonial import. In 2018, Theresa May offered an apology to former Commonwealth countries for Britain’s role in exporting homophobic laws to its former colonies. Yet individuals like Aderonke Apata who seek asylum in Britain on the basis of LGBTQI+ persecution in their home countries of origin are still forced to go through a barrage of degrading tests and lengthy court proceedings to prove their sexuality.

Unfortunately, apologies will do little in stemming the epidemic of STIs, HIV and homophobia amongst communities who have been driven into the shadows by stigma. The removal of colonial laws in former European colonies such as India, Fiji, Angola and South Africa does signal that in some countries, opinions are changing. However, many of these changes have been led by LGBTQI+ activists, and it would appear that LGBTQI+ communities, as usual, must be the first to act to protect their

Decolonising Contraception is a community interest company set up by people of colour working in sexual and reproductive health. Their next event, on LGBTQI+ people of colour, is on the 29 April at SOAS SU, 7-9pm