How are big companies still getting away with ripping off black women’s work?

Micha Frazer-Carroll

29 May 2019

Photography by Yomi Adegoke

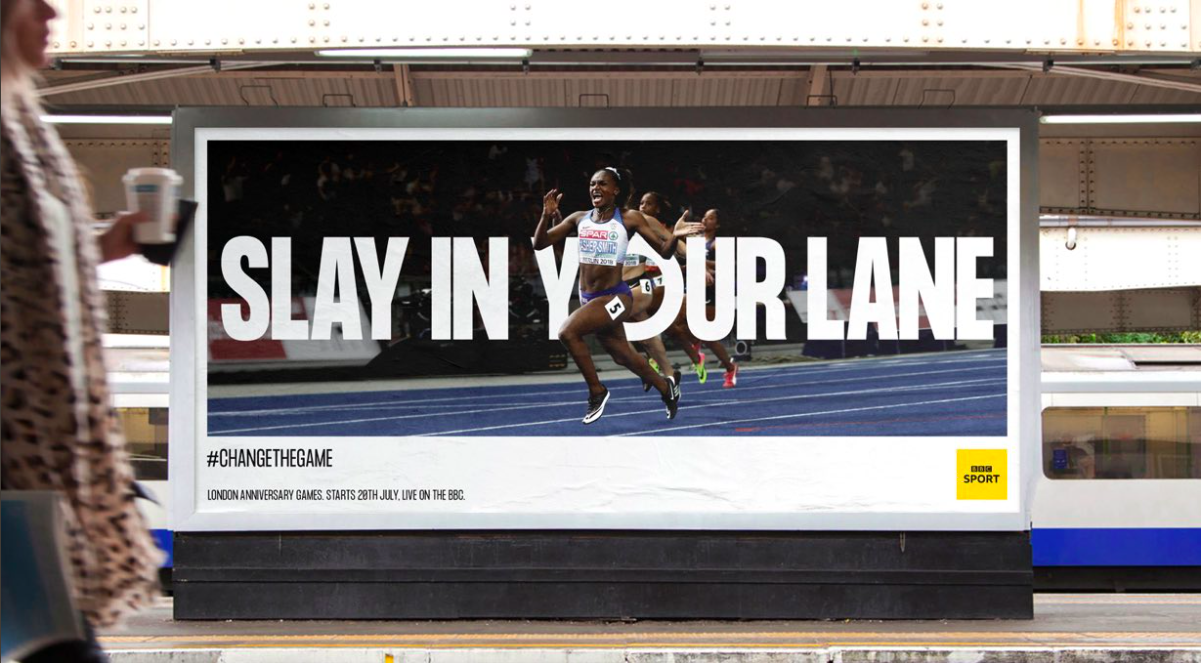

When is black women’s work going to start being taken seriously? Yesterday the BBC landed in hot water when Yomi Adegoke, co-author of Slay In Your Lane: The Black Girl’s Bible tweeted out a picture of the broadcasting company’s ad campaign on women in sport alongside herself and Elizabeth Uviebinené’s release, where she spotted a few…tiny…similarities…

The BBC released a statement saying: “[we] sought legal advice before going ahead and were advised that the use of the headline ‘Slay In Your Lane’ in our Women in Sport #ChangeTheGame marketing campaign was sufficiently far removed from the goods and services covered by the trademark registration in place.” That’s right, that means that a) the Beeb knew about it before, and b) they think the headline “Slay In Your Lane” is sufficiently different to book title “Slay In Your Lane”. We’re tired, and we know plagiarism when we see it.

Unfortunately they are not the first big company to steal the work of young black people, and definitely won’t be the last. Last year, Kim Kardashian released a cringy “kimoji” set featuring faux-feminist emojis – one of which bore the phrase “Slay In Your Lane”.

Beyond Yomi and Elizabeth’s book – last month young, black, queer artist Ashton Attsz accused designer brand Thom Browne of copying a prize-winning artwork that celebrated the bodies of genderqueer people of colour.

Ashton said at the time: “My painting … is a celebration of queerness, transness and blackness; an ode to everyone struggling, crossing our own finishing lines and winning at life. To have it replicated is sickening. Do better.”

Moschino and Sephora were also accused of stealing black CEO Raynell Steward’s idea for a school supply-themed makeup brand.

But the audacity of the Slay In Your Lane case feels particularly notable – the book was a bestseller and scooped the £10k Groucho Award in late 2018. To any black British woman with an internet connection or proximity to a bookshop, to target the pair’s hit release seems unbelievably brazen. So where does this flagrant disregard for black women’s work stem from? I spoke to Yomi to understand more about how cases of plagiarism play out, and the racist dynamics that underpin them.

One thing Yomi is sure of is that it’s to do with social standing. “I definitely think there was an air of: these girls won’t have it trademarked.” Two young black women may be able to write a bestseller, but perhaps BBC Sport assumed they wouldn’t have the business brains and legal foresight to think to protect their work.

“Can you imagine them writing ‘Just Do It’ or ‘I’m Lovin’ It’ underneath? They wouldn’t dare.”

Unlucky for the BBC, Yomi has a law degree and knew their rights. “With the Kim Kardashian case, obviously I was pissed off – it was pink and white, and very baitly inspired by it. But our copyright doesn’t extend to the states. But with the BBC, there was a case.”

“Legally, the term is ‘passing off’ – it’s a common law tort. When you try to represent your brand as another brand, or being affiliated with another brand, even if we didn’t trademark it, we’d still have legal grounds. By fronting it with Dina Asher-Smith, an amazing, prominent black British woman, they have clearly tried to pass it off as affiliated with our brand.”

“Can you imagine them writing ‘Just Do It’ or ‘I’m Lovin’ It’ underneath? They wouldn’t dare”

As well as the BBC underestimating Yomi and Elizabeth’s preparedness, there’s also the issue of the way society sees language attached to blackness as not being “owned” by anyone. Slang used in black communities has traditionally travelled through word of mouth, making it less documented, but also ripe for appropriation. We’ve seen the bastardisation and subsequent memeification of words like “woke”, “lit”, “squad”, “fleek” and “yas”, (all community phrases that eventually got picked up by brands). It’s possible there’s something similar going on here – after all the phrase has many of the features of slang used by black people, so maybe the white marketing team thought it would be easy to steal it without getting caught.

“‘Slay In Your Lane’ is the type of phrase that feels quite ubiquitous, it feels like something that’s pre-established,” Yomi says. “But all it takes is one quick Google to see it’s ours.”

“You’re not going to trademark the term ‘it’s lit’ because obviously these are slang terms. But with ‘Slay In Your Lane’, there’s a reason we have the Twitter handle, the website, the gmail address – it’s because we’d never seen it before.”

“It’s quite an obvious pun, but the fact of the matter is that we’d never seen it, and went out of our way to trademark it.”

For Yomi, the cherry on top of the cake is that black women are told that when our work is stolen, we should be grateful. It goes without saying that the BBC is a media giant, and exposure on their platform is more often than not framed as a positive for young, marginalised creatives, who might not usually get thrown into the spotlight.

“I think they thought that at the end of the day, it’s flattering that they’re even aware enough of our book to be able to plagiarise it. Like we haven’t been on that platform a million times and genuinely don’t even care.” In a now-deleted tweet, James Cross, who was one of the creative directors behind the whole campaign, accused Adegoke of “bullying” and “going after innocent individuals on social media”, demonstrating just how much we’re denied the right to be angry.

“I think they thought that at the end of the day, it’s flattering that they’re even aware enough of our book to be able to plagiarise it. Like we haven’t been on that platform a million times and genuinely don’t even care”

So, as black women, how do we stop our work getting ripped off in the future? In terms of advice for other creatives, Yomi says: “trademark your shit”.

“It’s a couple hundred pounds – if you do have the means, trademark it.” For those of us who aren’t publishing books or producing prize-winning art on the regular, that might feel like a concern far-removed from our lives, but Yomi explains that it extends to ideas. “Reni Eddo-Lodge has said if you have an idea that you can make into a Twitter thread, consider not writing a thread, and instead making it an article – because people often plagiarise Twitter threads.”

As for those big media organisations you see creeping in your Twitter follows? “Please don’t take that as flattery,” Yomi says. “They’re probably there to try and mine your ideas.”

Ultimately, the list of reasons why huge companies and brands think they can steal from black women is long. “This book talks about this all the time – white women and white people intentionally erasing the work of black women in particular.”

But the more we get educated on our rights, and what we can demand, the more the game is changing. We’re not obliged to be grateful. Yomi says to make no mistake: “this isn’t visibility, it’s erasure.”