How can black businesses and creatives achieve validation in a white world?

Imriel Morgan

28 Nov 2016

It has been a great couple of months for black excellence. Maybe it’s the circles I roll in, or the after effects of black history month, but we have seen some great press covering the success of people of colour. gal-dem took over the V&A, the BBC released Black and British, the ShoutOut Network got recognition for diversifying UK podcasts, Black Ballad hosted a Cocktails and Conversation and started a Crowdfund, and Jendella Benson and Nicole Crentsil both did TEDx talks. It seems that we have found our collective voice, and we are using them to shine, together.

Despite all of this excellence and black girl magic, it may come as a huge surprise to some of you that we are still woefully underpaid or not paid at all. I’m the co-founder of a UK podcast network called the ShoutOut Network, which has quickly established itself as the home of underrepresented voices. In September I was asked to be on a panel at the Radio Future Sounds conference in Brighton to discuss monetising our content (the most common route in podcasting is to advertise). The conversation focused on the difficulty of building an audience significant enough to attract major advertisers. According to Acast, the industry standard for US podcasts is 25,000 listeners a week. The ShoutOut Network’s potential audience only gets smaller when you consider that only 11 million people have reported that they listen to podcasts and when you consider the population breakdown within that.

At the end of the session, one of the station managers for Totally Radio approached me and matter of factly told me that the people who get the most benefit from your work should be the ones to pay for it. Which begged the question who is validating, consuming and reaping the benefits of all of our hard work? I realised that it is quite hard to quantify whether the answer was the volunteers contributing their content to our platforms or the people consuming the content our platforms provide. The answer is probably both.

“Which begged the question who is validating, consuming and reaping the benefits of all of our hard work?”

Many content creators for “niche” (read: people of colour) audiences have successfully found and slayed in our respective lanes. However, we can’t seem to get the cash to back up that success. That leads some of us looking at “white” organisations seeking to profit from black originality which leads to accusations of selling-out and risking our audience. Or just capitalising off it without out crediting or compensating the creativity or idea (#RIPVine). What happens if, after several attempts to get your audience to back you, it doesn’t work? Sharmadean Reid, the founder of WAH Nails, hosted the first Future Girl Corp event in October of this year. The event consisted of talks and practical workshops to help young female founders and CEOs. During the workshops, the phrase that rang out and resonated with many of us was that until someone starts paying for your product or service, you don’t have a business.

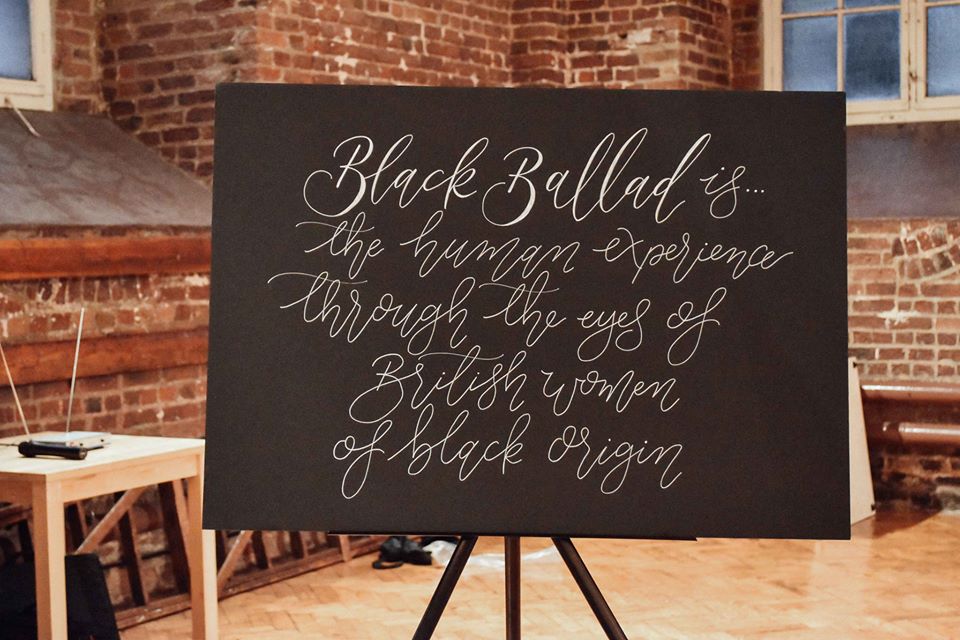

A few weeks ago, Black Ballad, a website for black and mixed race women in the UK, launched a crowdfund campaign. They are asking 1500 readers contribute to the platform in exchange for a subscription to their new service, which launches in May 2017. I caught up with Tobi Oredein, the co-founder and editor-in-chief of Black Ballad, who told me that, “It has been difficult trying to convince our audience to pay for content, but that has been because online content mostly been free. It’s a massive hurdle to tell a generation who have never had to pay to read an article that it’s now time to hand over your money for a women’s lifestyle publication.”

I hope that they can achieve that goal. In November the ShoutOut Network launched a 48-hour flash sale on podcast advertising to encourage black owned businesses to invest in black audiences. The total amount of money we could have made if the adverts sold out was £559 which doesn’t cover one weeks production cost. We sold 65 percent of the ads and we are immensely grateful to those who did support us and the sale but it wasn’t easy convincing brands (who listen and see the value in our content) to part with money. We’d all like to dispel the long-standing stereotype of black people not supporting black owned businesses financially, but it’s getting harder to find examples.

Some of us, myself included, are still guilty of touting our featured articles in the Guardian, Elle, The Times, etc. over our features in gal-dem, SBTV, The Voice and other BAME publications. When did the publications for us by us not become enough? I understand the desire to want to be mainstream, widely recognised and popular. However, it’s like walking a tightrope between loyalty and crossing over and catering to whiteness (read: selling-out).

Thankfully we can look to the success of grime as a genre which despite its burgeoning popularity it has remained remarkably true to its underground urban roots. I may doubt the longevity of grime in the mainstream, but there’s no denying that it has become a raging success for the black creative and the trickle down effect on other creatives in adjacent spaces.

“Are we exploiting traditional media or are we indirectly saying that our channels aren’t enough?”

Content creation is hard work. Many of us work full-time to remain consistent and loyal; we miss days off work for networking and growing our brands. We end up in embarrassing pitching situations trying to explain why the work we produce is necessary and worthy of financial investment to a table of white male investors (though this is changing rapidly).

It seems as though the plight of the creative, is to not only tirelessly work on putting out content for free, but to also create a physical product that is desirable to those consuming it. It is how we end up having events, books and merchandise which cost us more money and more time. The ROI can be hugely beneficial, but they are not without their troubles. We’ve all heard about events being criticised for being too London-centric. Until we all unite and create a mass movement together and tour that around the country, it’s unlikely that the lone creatives can satiate our growing national and international audiences.

Equal criticism comes when our brands become too commercial, and therefore untrustworthy. All the naysayers may not be volunteering to help out with the bills but if you don’t have a track record of loyal support do not comment on the ways we choose to survive. There needs to be a better way to support our creatives and business owners and secure the safe spaces everyone so desperately needs.

As horrific as 2016 has been for the world, there is hope for the black creatives. I’m just not quite sure what the future looks like for those of us that want to stay fiercely loyal to an audience that desperately needs the work but can’t or won’t support it in the way that sustains it.