How Joy Gardner’s 1993 death reflects the worst parts of the Tories hostile immigration policy

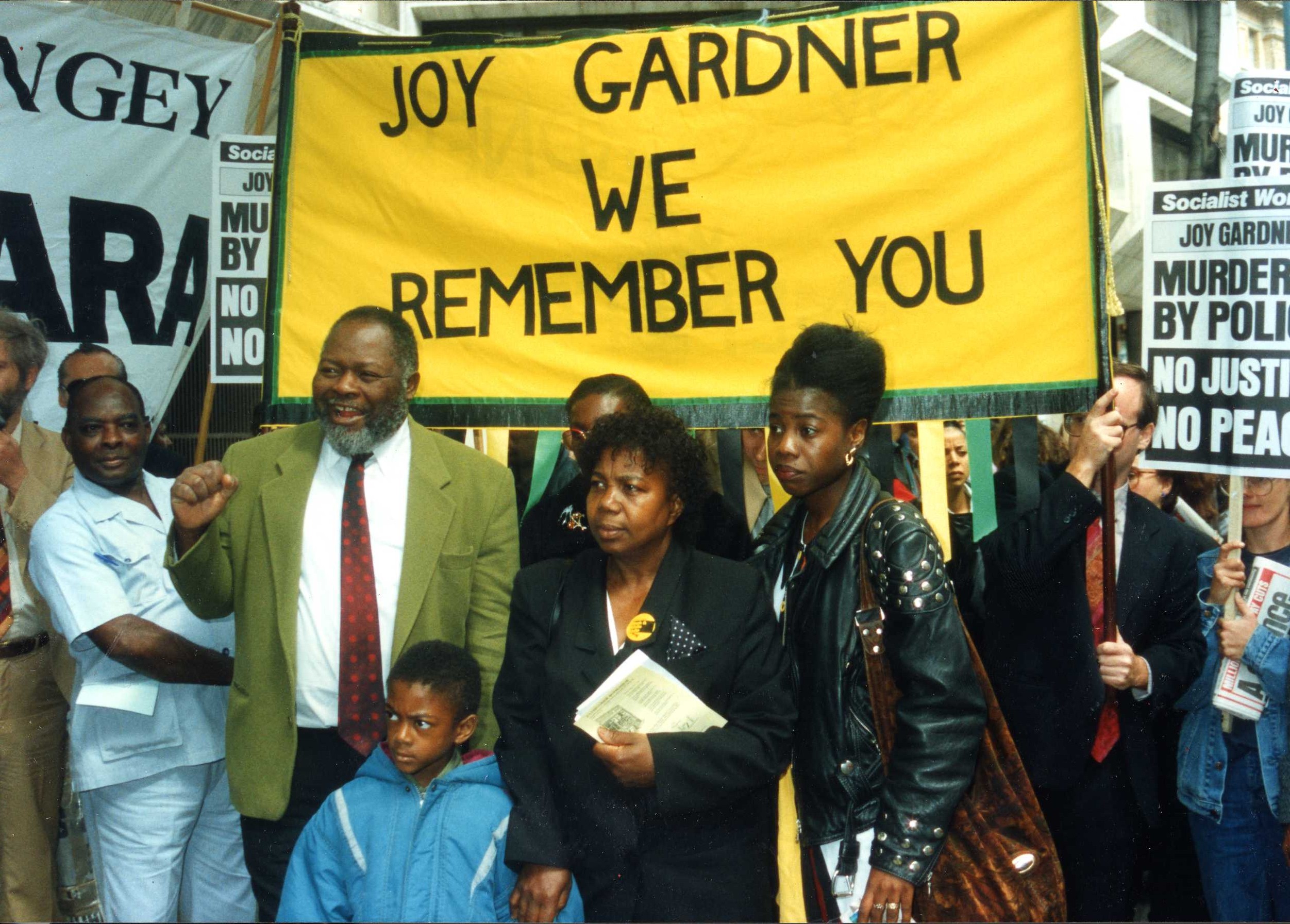

Joy Gardner died at her home in London during a violent, botched deportation in 1993. Her case, which has never been resolved by an inquest, shows that the deportations of Windrush-era citizens follow a pattern of hostile immigration policies that stretch back further than 2015. On the 25th anniversary of Joy's death, her mother, Myrna Simpson, is still fighting for justice.

Charlie Brinkhurst Cuff

29 Oct 2018

They put a leather belt around her

13 feet of tape and bound her

Handcuffs to secure her

And only God knows what else,

She’s illegal, so deport her

Said the Empire that brought her

– Benjamin Zephaniah

On Wednesday, 28 July 1993, police and immigration officers went to my daughter Joy Gardner’s at in Hornsey, London and broke down the door. They went in and took her out of her bed, where she had been sleeping with her five-and-half-year-old son, Graeme. They took them into the living room and sat on top of Joy, tying her hands with a leather belt at her sides. They strapped her legs and wound 13 feet of surgical tape around her head and face. They put a body-belt around her waist and leg irons on her feet. I think she died there and then by suffocation. That’s what the family autopsy said.

When David, my son, came over to my house to tell me that he’d heard from police officers that Joy was in the hospital, I thought that she had met an accident. I was living in Edmonton at the time, and I got dressed quickly to get to Whittington Hospital. I couldn’t believe what I saw when I got there. A few police officers milled around, and Labour MP and black activist Bernie Grant, who went on to help lead the campaign to get justice for Joy before he passed away himself in 2000, was there too.

They showed me to Joy’s bedside and when I saw her, she had strings and baking foil all over her, and a ventilator pumping air. I said, ‘What is the baking foil doing on her?’ and then I asked the doctor what was wrong with Joy. Her face had bruises on it. He said to me, ‘Mrs Simpson, let me be frank with you, Joy hasn’t got a chance.’ I was in shock. ‘What’s wrong?’ I asked. ‘Is her brain swollen?’ He replied, ‘Yes, her brain is swollen.’ And I said, ‘But she’s dead, isn’t she? She’s dead.’ He looked very sad but he didn’t answer me. I started crying and my children started crying. We were making such a noise in the hospital because I think we had gone crazy. Although we saw her, we couldn’t believe that she was gone.

Joy stayed in the hospital for four days. She was rotting in the hospital bed, and they had to spray out the room because of the smell. It was horrible. I slept on the floor for the four nights that she was there because they didn’t give me a bed. A church sister of mine came up and stayed with me. I only left to go and have a bath and get something to eat. After four days and nights, we had to turn off the life-support machine because they said that her kidneys and liver had failed. Her death is recorded as 4 August, but in my opinion, her organs had failed from the time she was in the flat. That’s where they killed her.

“They strapped her legs and wound 13 feet of surgical tape around her head and face”

I am a part of the Windrush generation. My first vote was in this country, and here is where I made my home and family. I came to Britain when I was only a young woman, in 1961, to pursue a better life for my children and to work. We who are the Windrush generation historically made sacrifices to enable British democracy to flourish. We have earned the right to have a level playing field when it comes to immigration. The hostile attitude that contributed to my daughter’s death must be put in the context of the current Windrush scandal.

When I got to England, I didn’t sit down; I worked in the snow, frost and fog as a care assistant, washing English people’s knickers and cleaning up their messes. I couldn’t even get a proper place to live. We used to stay in one room of a house and do almost everything in that room. The landing would be where we cooked. Some people might believe we had life easy, but we bore it rough.

Joy was only seven when she was left with my mother in Jamaica. She was my first child, who I had when I was only young myself, and I didn’t enjoy her back then. But I wanted her to stay in the Caribbean until I could provide for her in England. I would send money and visit her every year. When Joy came in 1987 she wasn’t illegal, she was legal. I paid £600-odd to bring her to this country. And when I came, 16 years before, I paid £75 for the aeroplane. She didn’t come on a boat or stow away. They maintained that she was illegal because she overstayed her six-month visa. And then they killed her.

We have to try to remember Joy as a student, as a mother, as somebody who was studying media. She grew up in Long Bay, Portland on the sea coast, and every Sunday, without fail, went to church with her grandmother, whether she liked it or not. That was the principle of our Christian family. She moved to Kingston to pursue her dreams but she got pregnant with her eldest daughter, Lisa. She wanted the best for her children and sent Lisa to a private school in Jamaica and had big plans for her future. She was strict and would buy Lisa books instead of toys so that she could start reading at an early age.

Joy went to study at St George’s College in Kingston and then she worked at a parish council in Jamaica, where she was given the nickname ‘Burkey’ (Burke was her maiden name). She left her children with my mother in Jamaica. Joy wanted to be a journalist before her dreams were cut short – similar to the case of Stephen Lawrence, who wanted to be an architect and was killed just two months before Joy’s death.

I’ve received no state assistance in fighting the case whatsoever. Joy’s inquest was postponed, and I don’t know why they didn’t ever reopen it. She was buried without the inquest reopening. When I went to a private barrister about the case, he said that there was nothing that could be done.

I’m sorry for the policemen who I believe killed her. Three of them were tried on manslaughter charges in 1995 and they were all acquitted. But you can’t kill someone and get away with it. Even if you get away from man, you cannot get away from God, because there’s a true and living God up above and he watches everything that every man, woman and child does. One day, the policemen are going to give account for the loss of Joy’s life.

“I’ve received no state assistance in fighting the case whatsoever. Joy’s inquest was postponed, and I don’t know why they didn’t ever reopen it”

Sometimes I think it will be on their conscience until they die, but other times I think that they cannot have had a conscience, because of the way they treated Joy – another human being. It shouldn’t matter the colour of our skin. We didn’t choose to be black, they didn’t choose to be white. No man should be a racist.

We miss Joy very much and I’m not glad that she’s gone from me, but I think she died for a good reason. She hasn’t given her life just ordinarily: she’s a martyr and she’s set examples for others.

I may be old but I’ll get justice for Joy. It’s not easy when you’ve lost a loved one. I’ve tried my best and I’m fighting. I’ll fight until I have no breath left in my body because I’m not only fighting for Joy – I’m fighting for everybody, whether black or white, if you have been killed unlawfully. Only God can take the life out of me, no man can take my life.

As of 2018, it’s been 25 years since Joy was taken away from us in a brutal way. I don’t wish it to happen to anyone else. But one day there will be peace in the valley.

An extract from an interview with Myrna that appears in the collection Mother Country: Real Stories Of The Windrush Children, edited by Charlie Brinkhurst-Cuff.