Hybridity is the new black. Like something Riz Ahmed (my fave) said on the Late Show with Stephen Colbert, I too used to feel the need to justify or elaborate my status as being British, a shield against the nagging fear of being “outed” as a phoney caught at the back of my throat every time someone asked “Where are you from?”. But, during this summer, I came to realise that actually – screw that, this is what British looks like and what Ghanaian looks like, simply by virtue of the fact that this is what I look like. The confused accent, dual citizenship, “um’s” and “it’s complicated’s” – all of it.

London is the West Indian who may have never physically visited the island but finds their home at Notting Hill Carnival, the bilingual South Asian who knows their grandparents only by voice through the phone, and well, me. We have stretched the flag wide enough for all of us, despite what some racist prick in parliament or some person from a middle-of-nowhere village nobody had heard of before the referendum think. In this day and age, it is at best delusional to try and ignore the multi-faceted culture behind the Union Jack and that straddling two or more cultures on your back is the story of like… Everyone.

***

Going back to Ghana for me is like thrusting my body off of my bed and out of sleep paralysis – equally as liberating as it is terrifying. Being awake but still physically asleep is very much like how I experience the ennui that comes with being consumed by a particular place for too long. Physically uprooting myself gives me the jolt back to reality that I need to remember that those other places and people that I have compartmentalised in my mind as incongruous memories, in fact, do actually still exist. The smells, the colours, and language around me seep into my consciousness and abruptly rattle my dream-like state of displacement.

I can’t fully explain it the way I would like to, but as a British-Ghanaian black woman living in America, it always feels as though my conversations and existence are at any given time, conforming to a particular part of my identity, as opposed to my experiences wholly. Therefore my understanding too, is fragmented across arbitrary lines and borders. This skewed reality manifests itself as confusion; I often do not feel fully real – parts of me feel visible, while others are afterthoughts. It’s like there is this unspoken obligation to pick a side or stay on one track, and I always end up feeling guilty or incomplete. Almost like I am turning my back on something.

‘How did I get so lost in my own identity?’

Ideally, my politics should encompass the many spaces that I occupy but even my blackness means different things in different places, and navigating this has not always been easy. In Ghana, my African-ness is the default (not to be confused with the most powerful, a subtle but important difference) and is somehow divorced from my blackness despite all the ways in which the two inform each other in historical global systems of power. In Britain, I am read as familiar unknown, despite my having been here since birth, and in America, I am black but foreign. My identity is often at odds with itself – Black, British, Ghanaian – but like that scaringly striking quote by Audre Lorde that is plastered in all my notes, “If I didn’t define myself for myself, I would be crunched into other people’s fantasies for me and eaten alive.” So how did I get so lost in my own identity?

***

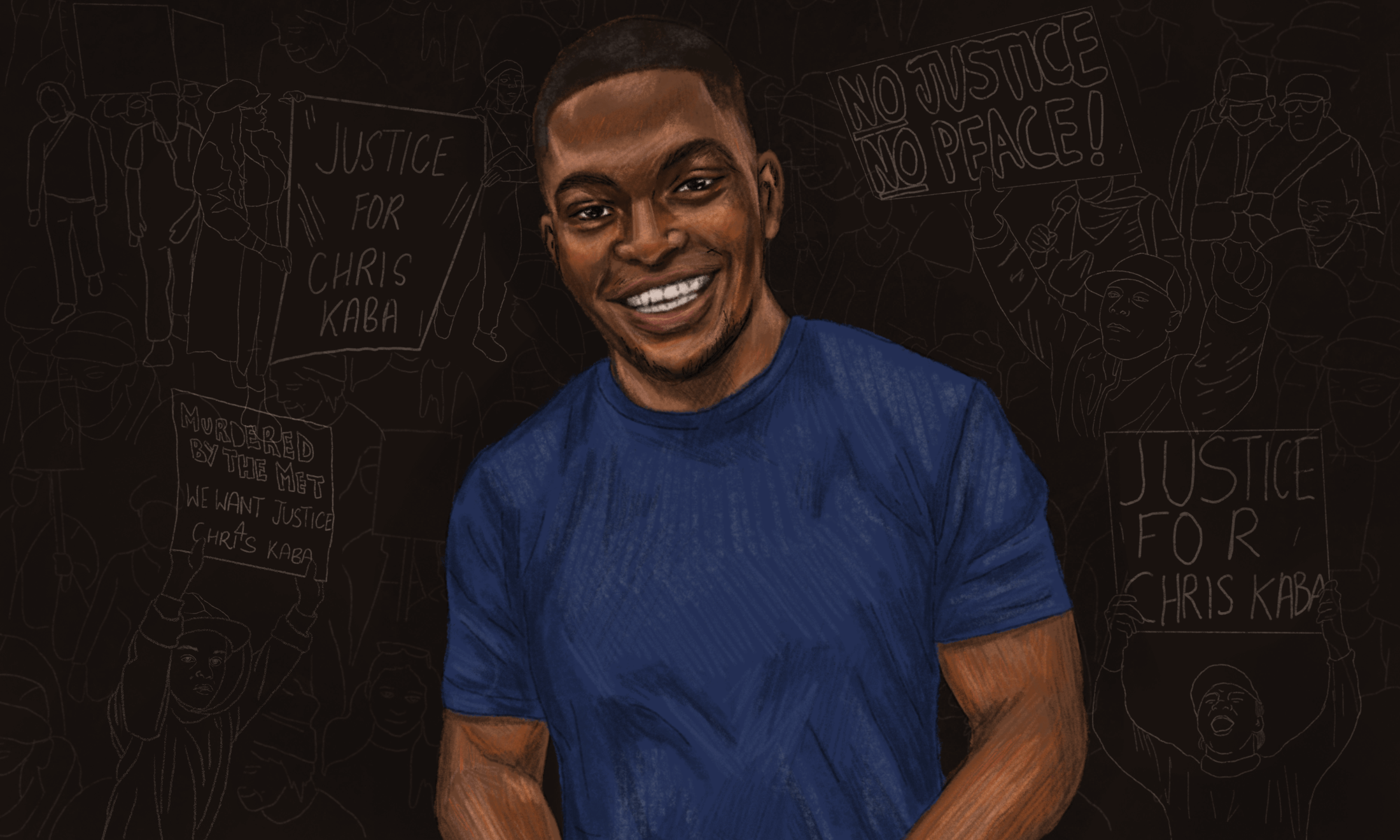

The morning I woke up to the death of Alton Sterling in Baton Rouge, I bounced between checking Twitter for information that would explain the madness and restraining myself from reading comments or replies out of self-care. Sitting on my cousin’s bunk bed in rural Surrey, I was far removed from the epicenter of it all, but felt the shockwaves all the same. The days that followed were no different. If anything, the subsequent UK Black Lives Matters protests that shone light on those that had been taken from us on our own soil as we faced the Atlantic Ocean, exemplified what I already knew: No place I call home is “safe”. These to me, were no longer separate galaxies but rather worlds flowing into each other. The pain that I felt was, no, is valid, and while it usually passes, being black and woman, I am no stranger to gnawing helplessness hiding just under the surface, waiting.

In the moment of my comfort I am forgetting myself, when I can. I’m starting to realise more and more that safety has always been an illusion and a combination of ignorance and privilege – when I am comfortable it is because I am forgetting something, be it poverty, police brutality, white supremacy, neocolonialism, the mess that is this world etc. Why do I have to ignore my personhood and reality to be comfortable? Black happiness should be as a result of our magic, not in spite of it.

‘Black happiness should be as a result of our magic’

Therefore, my growth and and attempts to better decode my existence in this world are intrinsically tied to understanding what this means when you exist in many different ways. I’m not speaking to geographical ambiguity – although that is one way in which this occurs – but rather how to a large extent, we all live textured and multi-dimensional lives and thus navigate through this world in different ways at different times. Like a touch-me-not, I often conform to fit the shape of the environment I find myself in. How am I perceived in America, in Ghana, and in Britain and how do these influence how I present myself? What descriptors do I tag onto my person depending on who is asking- do I say black, British or Ghanaian first and how do I address one without negating the other? It is the same ‘me’ but I am understood differently in each place, and adjust accordingly.

For example, a question as simple as “where are you from?”, depending on what I think you want to know, could reveal different homes: “which passports I hold” home, “where most of my stuff is” home, “where most of my stuff that I actually like is” home or “where my heart currently is” home, or even the exact village and tribe I come from. I’ve never been one for nationalistic essentialism and what with my whole 21st century identity crisis “I fit in nowhere and everywhere” shtick, rooting my sense of self firmly to one place would only make room for heartbreak and possible awkward interrogations to test my authenticity.

Well, then how do I account for “everything”? I don’t quite know for sure. To say “intersectionality” and leave at that, would be to lazily use the word without explanation. To give a more tangible example, projects such as Cecile Emeke’s Strolling are so important in facilitating a much-needed diasporic conversation and fill in the gaps that can’t always be seen. We need to expand our definitions of blackness because it is so varied and beautiful in diverse ways, yet we all see home in one other.

Only, we usually do so without actual engagement. This is how I feel after attending a great panel or having an inspiring discussion and realising that for all the talking and thinking I may do about race, how often do I think about how this informs structural global poverty, cultural imperialism and colorism in Ghana, and Africa at large or the invisibility of PoC experience in a “post-racial” Britain? This is not to compare issues on a scale of bad to worse- that would be flippant and erroneous, only to demonstrate that these are simply branches of the same tree, and that is what I need my politics to entail. It’s just hard when some are more visible than others.

***

Politics starts at home and so, I guess, does understanding the root of your politics. It definitely does encourage me to look at things wholly and try and make connections in what could seem like polar opposites. But, more than anything, I feel like I am getting somewhere when I look inwardly. I can look at my personhood as a physical embodiment of these connections- every scar, every weird twang of my accent and every time I mould one part of myself to make room for a more appropriate one – as the beginning of my analysis. Who am I, what/who changes me and why? More so as a person, how do these inconsistencies exist within me – how am I privileged, marginalised and what does it mean at times to occupy some spaces simultaneously and yet speak for one at a time?

So this is me, speaking to (in)visibility, transnational struggles and forgetting. This is me, attempting to reconcile that indescribable feeling I have when I scroll through my timeline and realise I am paying more attention to tragedies in the U.S because I have gotten tired and become desensitised to the everyday ongoings on my continent – the one I feel when I know the names of those who should never had to die, but did, at the hands of police brutality in the United States before those of the people who call London home too, at the hands of the people who claim to “not see race” but are just as bad and get away with it because of this lopsided silence. This is me, trying to bridge the gap by thinking, speaking and living in multitudes.