‘I was screaming but there was no one around’: the exploitation of domestic workers in the Gulf region

Victoria Basma

17 Jul 2018

Content warning: descriptions of abuse and violence

Having recently moved back to the Middle East, I have become one of many young Middle- Easterners who are choosing to take part in a type of “reverse-migration”. In a year that has seen the rise of right-wing anti-Muslim movements across the world, moving back to the Middle East has been part of a great opportunity to re-centre myself. As part of a conscious effort to rebuild a connection to my culture, I have become part of a community that no longer sees me as the “other”, but rather as one of their own.

Although I have increasingly felt fulfilled by my experience of re-joining a community that I can identify with, I have also become cognisant of the fact that I have become part of a privileged class that enjoys the many social and financial benefits of being part of a Muslim-Arab majority. My search for a community of my own has rather unwittingly led me to become part of a system that consciously works to create boundaries around an “other” for my benefit and those like me.

“My conversations with those back home often revolved around how different the UK and the Gulf region were”

When I first moved to the Middle East, my conversations with those back home often revolved around how different the UK and the Gulf region were; in the Gulf life (for some) is so easy and the “service” (a euphemistic reference to domestic labour) so cheap. The novelty of being able to have a five-hour cleaning service for under £50 has never quite worn off, however the pangs of guilt have certainly languished and have evolved into moral quandaries that I now have to grapple with.

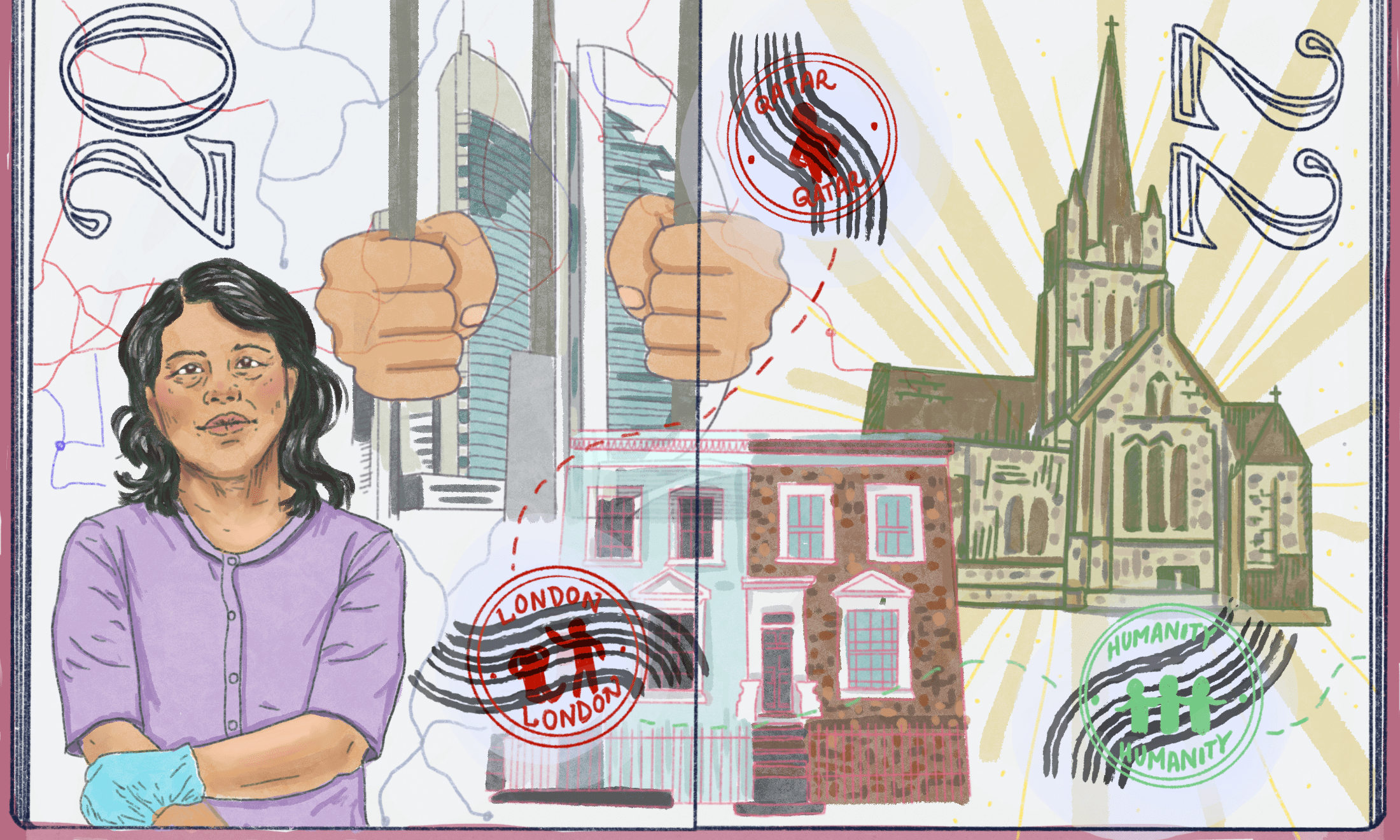

Over the last few years, the experiences of foreign workers in the Middle East have increasingly come into the spotlight. In a 2014 study carried out by Human Rights Watch, many workers reported their experiences under some employers as dehumanising and traumatic. Tahira S., a 28-year-old domestic worker from Indonesia described being abused within weeks of starting work: “she hit me…scraped her fingernails to my neck, slapped my face…sometimes she pulled out tufts of my hair”. Other workers gave accounts of sexual abuse, like Arti L., an Indonesian worker who was routinely raped and molested before she finally escaped: “I fight him, I was screaming but there is no one around…[eventually] I ran away […] I was bleeding badly”.

Despite endless documented cases of abuse, torture, and suicide of domestic workers – particularly within UAE and Gulf regions – there has been little effort to improve conditions.

“In 2016, Joanna Demafelis, a Filipina worker in Kuwait, was brutally beaten by her employers before finally being murdered”

In 2012, 33-year-old Ethiopian domestic worker Alem Dechasa was violently attacked outside of the Ethiopian consulate in Beirut. Whilst she was savagely beaten and dragged back to her employer’s BMW, a group of men silently looked on. After being transferred to a psychiatric hospital for medical care, Alem hung herself. In 2016, Joanna Demafelis, a Filipina worker in Kuwait, was brutally beaten by her employers before finally being murdered and stuffed into a freezer in an abandoned apartment; she was found more than a year later. As recently as April of this year, Agnes Mancilla, a Filipina worker in Saudi Arabia, was hospitalised after being forced to drink bleach by her employers. This was after two years of being physically beaten and burned.

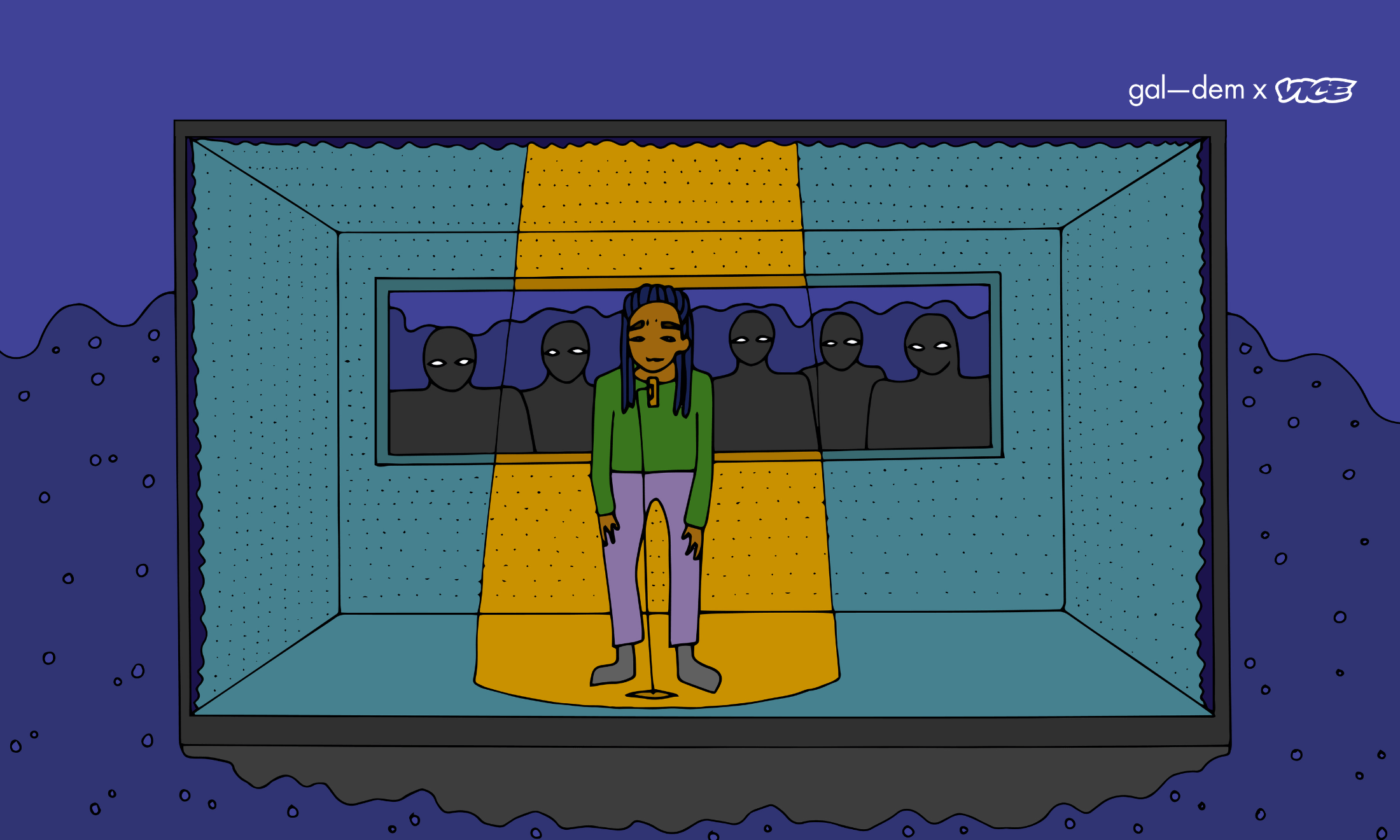

In 2017, Kalayaan, the UK’s leading organisation for domestic workers, published data on the reported levels of abuse. According to their study, 63% of workers reported having no access to regular food and 81% claimed that they were not allowed to leave the home unsupervised. In an interview last year with the Guardian, one domestic worker said that her employer “kept pushing on my mind that you are just a slave for me”. These are only a few examples: the dark truth of the matter is that there are far too many accounts to represent the scale of injustice and abuse.

“my relative privilege means that I have no doubt participated in the distorted power dynamic which sets the context for poor treatment”

The violence and exploitation perpetrated by these women’s employers are far from exceptions, but nor do they provide a complete picture of what it is like to live in this part of the world. Not every employer is abusive or violent; however, there is a spectrum of experiences that every foreign worker has that is part of being perceived and treated as a “second class citizen”. The off-hand and micro-aggressive forms of racism, and the invisibilisation and blatant disregard are part of this spectrum. My relative privilege means that I have no doubt participated in the distorted power dynamic which sets the context for poor treatment and abuse.

When I choose to pay a worker well below my understanding of minimum wage, or visit a home where domestic workers cannot look their employers in the eye, how do I reconcile this with my own feelings and experiences of having been an “other”? In the UK, my experiences were founded on the ideas of what it is to be an immigrant and working class, so how then do I justify becoming part of a system that exploits these communities because of these exact same qualities? It leaves a particularly bad taste in my mouth when people of colour choose to undermine each other. I have become trained to recognise and understand white privilege, its systems of exploitation and language, but it seems that even in its absence, privilege merely shifts; it is still web made up of cultural bias, a legacy of past colonial ideology that remains an absolute of life for foreign workers here.

Over the last few years, there have certainly been efforts to revise policy and legislation relating to the lives of domestic workers in the Middle East. In 2017, both the UAE and Qatar introduced new laws that aimed to protect the fundamental rights of domestic workers, providing stipulations around paid leave, working hours, and daily rest periods. However, whilst this is certainly a step in the right direction, these new government policies still fail to give adequate guidelines around accommodation and food, and reinforces the kafala system which ties domestic workers to their employers, preventing them from changing employers without their consent. This means that domestic workers are still constantly at risk of imprisonment or deportation if found “absconding” from their contracts.

We live in times when the status quo feels like it can and is shifting. However, movements like #MeToo and #TimesUp often continue to operate like platforms reserved for privileged, often white, wealthy women. There is a quieter struggle taking place behind the doors of some of our wealthiest neighbourhoods, and it is time that we make efforts within our communities to shed light on this issue; to hold policy-makers to account to improve the lives of domestic workers globally.