The fact that we live in a racist society is rarely disputed in polite “liberal” company. However, most people balk at the suggestion that they themselves might be racist. In impolite company, explicit racism is allowed to come out and stretch its legs – however, these people might deny that we live in a racist society at all. Racism, by all individual white accounts, appears to no longer exist.

What is racism, then? Is it, as “good” liberals seem to claim, a somehow disembodied notion, not attached to any single individual? Does racism exist at all? Many white people and in fact, many people of colour, have claimed it doesn’t, even if they claim so whilst simultaneously wondering why all black people must make everything about race (subtext: “perhaps they aren’t as reasonable as white people are”)?

If we accept Junot Diaz’s claim that when we say “racism”, we really mean “white supremacy”, then things become slightly easier to organise and define, at least in the West. We should also note white supremacy’s person-of-colour cousin in this definition – let’s call it “light supremacy”.

So, who in the West, is racist, and what makes them that way?

The question seems incredibly complex, but I’m going to go out on a limb and say that it isn’t. A racist person is someone who does or says a racist thing, no matter how tiny, subtle or perfect their track record, Our unconscious behaviours, slip-ups, and one-offs (things we do and say when we momentarily let our guard down) often betray our subconscious thoughts.

I’ll pause here to say that I know I am racist. I have caught myself thinking racist thoughts about virtually every race, including my own. I’ve always maintained (out loud) that the worst kind of person is one that has racist thoughts towards their own race, but the truth is, I haven’t yet rid my own mind of them. I even think racist things about myself. I often find myself in front of a mirror feeling dismayed at how dark I am, thinking that even my thighs would somehow look better if I wasn’t as dark.

I feel and think all these things because I was raised to feel and think them, and I’m not the only one. Teachers display subconscious bias against their black kindergarteners, and an analysis of online dating activity reveals a pro-white bias here as well. Racism is clearly alive and well – if not in people’s conscious thoughts, then in their subconscious ones. However, perhaps our subconscious thoughts don’t make us who we are. Maybe our conscious efforts to see our thoughts for what they are and then counter them with logic and sensitivity are what make us who we are.

We live in an institutionally racist society, which I would argue is populated almost entirely by subconsciously racist people. We can’t all be bad people. To acknowledge our own racism then, might not be to embrace our own “badness”, but to actually get to grips with what racism is. Its definition is still elusive, but our threshold for what constitutes racism might be considerably lower if people are given moral permission to admit that they are racist but are working on it. Otherwise, the publicly accepted definition will remain what white people decide and whether they deem their own thoughts racist or not.

Furthermore, a society in which “nobody is racist” cannot hold anybody responsible for fighting racism. On the other had, in a society where everybody is racist (i.e. a subconscious promoter of white supremacy), everybody is responsible for combatting it. If we acknowledge that much of racism is subtle, difficult to notice, and often unintentional, then we can begin to formulate a viable means of contesting it.

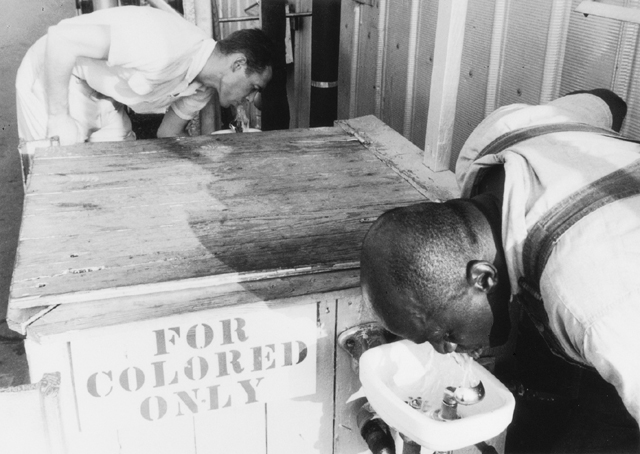

Institutional racism is, after all, just the accumulation of many subconscious ideological choices and instincts – a white employer choosing not to hire a black applicant because of their name, members of influential institutions choosing not to support affirmative action because they are able to turn a blind eye to the residual effects of institutional racism, a white police officer instinctively shooting a black man because in the heat of the moment he truly felt that the man, because of his skin colour, was dangerous.

Being racist is perhaps a fact of life in modern Western society. We should shift the blame, and the responsibility, from what is subconscious to what is conscious. This could change the point of conversation from, for instance, “Is shooting an unarmed black teenager racist?” – which the police officer, along with everyone that identifies with him, must either deny or face the uncomfortable verdict that they are irrevocably Bad People – to, “How can we intensively train police officers to overcome their instinctive prejudice against black teenagers?”.

This also shifts the burden from the victims of racist thought to the beneficiaries of it. Black people, for instance, shouldn’t have to prove that mass incarceration of black people is racist. Instead, white people should have to answer the question of what they propose to do about it.