Image: Wiki Creative Commons

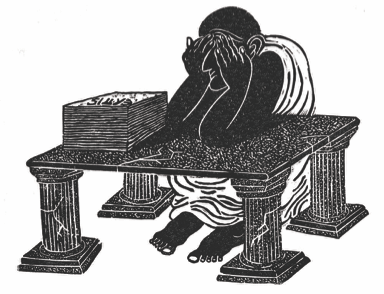

Internalised homophobia destroyed my last relationship. Sometimes going through a break-up teaches you things; you learn to recognise what really matters to you, or come to understand how you really feel about certain situations or how to deal with loss and grief. But what happens when you realise in the throes of heartbreak, that actually, your relationship was destroyed by your own self-hatred and unconscious beliefs, views you didn’t even know you had?

We were each other’s firsts but wasted far too much time worrying. We were worried about being found out for being together, whilst simultaneously remaining furious that we weren’t welcomed into London’s lesbian scene. We worried that we weren’t “gay enough” but also worried about feeling like imposters. Unnecessary PDA on the Victoria line in the name of representation characterised our relationship, and we mistakenly thought our new, womxn-oriented lifestyle would elevate our brand of feminism to new heights (it didn’t). Yet my biggest worry throughout our time together, was that upon finding myself in my new sexual identity, I also lost the only home I ever had.

“Where were we really from if our communities would reject us for being ourselves?”

I grew up in the UAE, living under the watchful eye of an Islamic patriarchy, intolerant of gay relationships and supportive of homophobia. Even today there is no recognition of same-sex relationships, with the consequence of such “consensual sodomy” being up to 14 years imprisonment in some Emirates. Heteronormative gender roles are heavily enforced in mainstream society, so it took me over a decade to begin resisting the cultural context in which I was praised for being an obedient daughter, trained to aspire to be a submissive wife in a heterosexual marriage, and shamed by for attempting to view myself as a sexual being with agency.

I realise now that my culture is partially responsible for eroding my sense of self-worth, constructing a harmful internal narrative where I couldn’t imagine a relationship for a woman to be one without a man by her side. Discovering I was a lesbian felt inconvenient and it took years for me to acknowledge because I didn’t even know it was an option. To embrace this part of myself, I felt I had to immediately and swiftly dispose of others in the same movement, and I had no clue where to begin.

“Where were we really from if our communities would reject us for being ourselves? Were we really who we thought we were if we could so easily slip between the lines of the crude double-lives we had constructed?”

Falling in love with my ex made me feel like two halves of myself were at war with one another. Over and over again I would break, my cultural identity becoming more splintered with each “I love you”. I sensed she was fighting similar feelings, but we couldn’t find the words to talk to about it. She was a lesbian and proud of her South Asian heritage, but much less so of her sexuality. I think she was battling with internalised homophobia, too. – simply the price you paid for the privilege of a community that shared your culture. I understood the pressure she was under and watched her struggle to toe the line between tradition and truth. With no obvious representation in our immediate worlds and no socially constructed script to guide us, we spent our nights frantically searching for answers, rather than enjoying one another. Where were we really from if our communities would reject us for being ourselves? Were we really who we thought we were if we could so easily slip between the lines of the crude double-lives we had constructed? I felt like a hypocrite – would there ever be space for women like us within our communities? How could this ever work long term? I couldn’t help but feel resentful that even our truth, the open acknowledgment of our sexuality and romantic relationship, felt like something only available to the truly privileged. I couldn’t imagine what it would be like to live free from the judgement of others, let alone free from the judgement inside our own heads. I stagnated, having lost myself. Eventually we broke-up.

“We worried that we weren’t “gay enough” but also worried about feeling like imposters.”

Maybe our internalised homophobia had won. I wish we had been better equipped to dismantle the walls constructed in our heads by years of experiencing and absorbing homophobia. Brick by brick, these lessons can be unlearned by all of us as long as we don’t put down our tools out of fear of trying. Although she changed my life, I was too distracted by the raging internal conflict between my feminism and the struggle to accept myself to ever be fully present when I was with her, and that’s something I can’t help but regret.