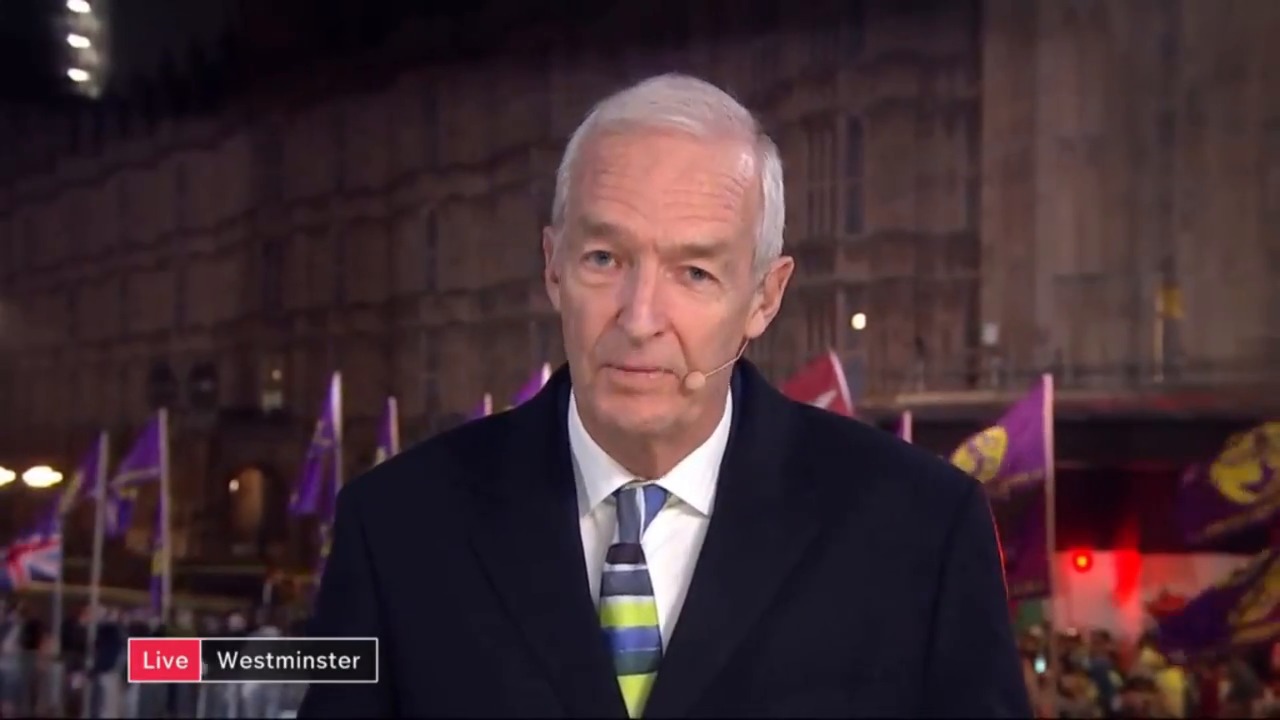

Image via Channel 4 News

When Jon Snow, tired after a week of reporting, looked deep into the camera’s lens at a pro-Brexit march and said, “I have never seen so many white people in one place”, something about the remark spoke to my soul. It seemed like a bold comment for national television, but not one that many people of colour on the left would dispute.

Of course, there was outrage. Some of the criticism of Snow’s comment focused on the idea that it was unnecessary, but others were outraged by the use of the word “white” in and of itself. Either way, Channel 4 churned out an apology within 24 hours.

It’s a strange time that we’re living in, but this is 2019 racial politics. As a person of colour I’m so accustomed to being identified as black, brown, mixed – whatever label white people ascribe to me. Why is it still uncomfortable, still taboo, for white people to be called white? I spoke to some white friends, rather than experts, about how everyday instances of being called “white” made them feel, offering anonymity to create a more honest conversation.

“Growing up, we’re taught that whiteness is the default”

The first issue might be that white people aren’t used to being categorised like people of colour are. “It doesn’t happen very often,” one friend told me, whilst searching for her answer. White academic Robin DiAngelo, who has dedicated her career to whiteness studies, argues along these lines. She thinks that one of the biggest stumbling blocks in terms of confronting racism is not ever referring to whiteness in the first place. She told the Guardian in February: “We have a pattern of whiteness never being named or acknowledged.” Never being associated with a label, then it suddenly coming out of the woodwork every now and again, can naturally be uncomfortable.

And DiAngelo is right – growing up, we’re taught that whiteness is the default. “We’re educated and socialised in a way where labels and categories have traditionally only ever been given to ‘others’,” one friend said. Thus whiteness is something you can deviate from, but not something you can be. It’s what makes us assume the Simpsons are white (yes, there are brown people, but the people shaded in yellow still default to what we know the contrasting “normal” American family to be). It’s also the reason why only the people of colour in fiction get described as being “caramel” or “coffee” or whatever other foodstuff matches up with their skin colour – if there’s no mention of it, we’re usually picturing someone white. It’s a word that goes unsaid, so when it’s said, for many white people, it jars.

There’s also the issue of individuality. More than one person I spoke to also felt that being grouped in with other people made them suddenly feel subject to generalisations and stereotypes. They felt as though they were implicated in other people’s actions.

In the case of Snow’s comment, there was obviously an underlying, contentious assertion about the overlap between Brexit supporters and racists. Beyond that, if you don’t want to be attached to a whole host of behaviours associated with a grouping you’re a part of, this can cause defensiveness. “It’s always slightly tough, having to take responsibility for a whole load of people you only have one thing in common with,” another white friend said. “But guess what: minorities have had to do that forever.”

Most people don’t like to be stereotyped – but when it’s a stereotype based on your structural advantage, there’s something distinctly “not all men” about using it as a defence. When we say “white people”, we don’t mean white people on an individual basis, but something far broader. One friend said that while she felt grounded in structures of marginalisation and how they worked, being reminded that she was a white person was like a repeated wake-up call that she was not exempt.

“When someone calls me white I’m like ‘oh yeah, I’m fully involved in that'”

“When people are called white, they don’t get to define that they’re the Good White People who would never do A Racism,” she said. “And when someone calls me white I’m like oh yeah, I’m fully involved in that. I think this kind of reminder is what people don’t like.” It makes sense. Even if you can conceptualise the struggles of a particular group, that’s often the easy part. The hard part is turning the focus on yourself, and how you participate in it. But that starts with remembering to say it.

Simply discussing the existence of “white people” isn’t racist – although it’s fair to say that ascribing certain behaviours to any race is a generalisation, which often isn’t useful. But there’s still a clear distinction between applying generalisations to groups that are structurally advantaged, and those that are disadvantaged, thanks to the power dynamic.

In perhaps the most obvious conclusion of 2019 so far, it feels important to acknowledge a basic fact: white people are white. As Uncle Snow gazed over crowds of Brexiteers after not only a week’s worth of reporting, but two years of racialised contention, he made what Channel 4 called in their apology an “unscripted observation”. And it was just that, an observation –there were lots of white people indeed. For white people, confronting and sitting with whiteness may be uncomfortable. But avoiding thinking about structural advantage, or naming it at all, only gives it more power.