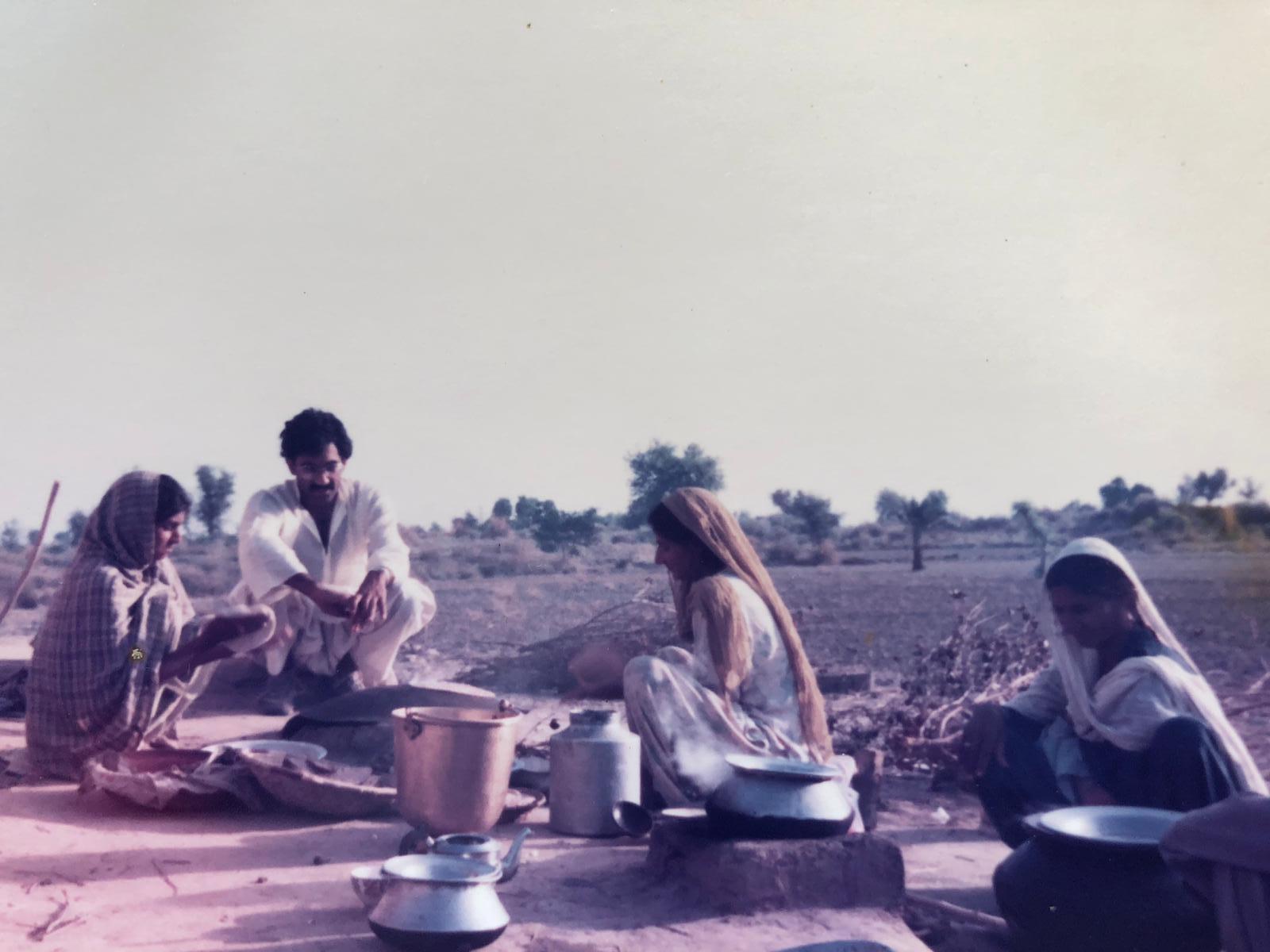

Following critical acclaim and a sold-out run at the Young Vic, The Jungle is moving to the Playhouse Theatre for another run. The Jungle, set in Calais, is a touching exploration of the lives of those living in the self-built communities in the north east of the port between 2015 and its destruction in 2016. We’re taken into the Calais camp and follow the lives of a group of displaced people learning to live together, all whilst trying to get to the “safe” shores of the UK. Soon joined by British volunteers, the group must work together to survive, to travel, and to eventually save the camp. We get to sit in at the Afghan café listening in on the stories of those who lived, helped, and eventually fought for the Jungle. I was lucky enough to catch up with Nahel Tzegai, who plays Helene, an Eritrean woman taking on the role of the matriarch and voice of Eritrea in the camp. We sat down to discuss The Jungle, migration, and diversity in theatre.

“The Jungle, set in Calais, is a touching exploration of the lives of those living in the self-built communities in the north east of the port between 2015 and its destruction in 2016.”

One of the most impressive aspects of the play by far is the set and use of space. Audience members have the choice of viewing The Jungle in two very different settings: the stalls of the Playhouse are transformed into the Afghan café with audience members sat out on benches amongst the actors. For those sitting here, you find yourself right in the the thick of the story. The the circle seating remains traditional and is referred to as the White Cliffs of Dover; from here, audience members can only partially see the café. Nahel likened the unique seating arrangements to Plato’s cave allegory. “You see the shadow…you see a shadow of something that you think is real but you can’t really experience it unless you’re in the mix”. The use of the White Cliffs of Dover as a separated space speaks volumes. Sitting here, you’re only partially viewing the story. Nahal explained, “It’s almost how people in Britain think they know what Calais is all about but they don’t really, they’re on the White Cliffs of Dover just looking from far away.”

By structuring the seating in this way, the experience an audience gets from the “Dover” circle will never really replicate what it’s like to be amongst the chaos, laughter, and community in the Afghan café. For Nahel, working in such a dynamic space added to the experience. “Of course I think about the audience”, Nahel explains. “They’re there, to me they are a part of it. The Café is the main character of the show so the people in the café are really important.” Nahel’s right – sat inside the Afghan café, you do feel a part of the story, and a part of the characters’ tumultuous journeys. “I’m an energy person; the audience right next to me are going through the motions with me and so it’s almost like a sense of community.” It’s this idea of community that really holds the story together.

“The Jungle is in the canon of plays, paving the way for ethnically diverse theatre and proving that it is needed and profitable.”

Nahel’s character, Helene, is critical in the play, representing not only Eritrea, but also women in a typically male dominated narrative. Luckily, and a rarity for Nahel, she was playing someone from her own background – “I’m a limbo kid, I’m from the first generation to be born outside of Eritrea” – so, for her, the portrayal of Helene was personal. “I knew a lot of people who were in the Calais jungle and my mum still fosters two boys who are Eritrean who went through Calais as well.” Doing justice by Helene was imperative.

Helene is strong matriarch, loud and confident, but also a calming presence in the camp. The idea of strength and what that means for black women is difficult and something that Nahel Tzegai struggled with. “My idea of strength is allowing yourself to be vulnerable”, but Nahel has to rectify that this portrayal wasn’t for her. “Me as Nahel I’m thinking…do I want to represent an angry black woman? But I understood and I realised it’s not about me ….I have to represent it for someone who was there and had to come up against these challenges.”

The Jungle is important because it’s in the West End and it has an ethnically diverse cast focusing on the stories of displaced people of colour – this is still such a rarity. Nahal explained: “I never really felt like I had access to the theatre, I felt really odd being there in a room full of middle class white people …[it] doesn’t feel like a space you’re invited to, does it?” Unlike the majority of mainstream theatre, The Jungle, much like the actual camp, is a space for all people from all walks of life.

Something that seemed near impossible for Nahel was playing someone from her own background in the West End. “I’m a black woman but I’m a niche black woman in the sense that I’m East African, I never saw anyone who looked like me.” The Jungle is in the canon of plays, paving the way for ethnically diverse theatre and proving that it is needed and profitable. Having this amazing cast including actors that actually lived in the Calais camp was a true mark of a play that respects authenticity in ethnic diversity. As Nahel put it, “hopefully if we do really well then that sets a trend – it’s the same in film. When black films do well they realise ‘people do watch this! Oh my God, Black Panther made so much money; lets make more!’” Nahel continues, “We need to see ourselves reflected back to us in some way shape or form. We have an urge and desire for that and now it’s happening.”

The Jungle will also be travelling to America, which couldn’t come at a more appropriate time considering the Trump administration’s recent immigration policies. The separation of children due to rigid immigration laws is reflected in The Jungle – “In the play there’s a young child walking around all the time.” The young girl doesn’t speak, but she’s forever present. “These unaccompanied children and how much they need parents and love is devastating; to be seperated is such a horrible thing.”

“Having this amazing cast including actors that actually lived in the Calais camp was a true mark of a play that respects authenticity in ethnic diversity.”

The Jungle is humbling. It perfectly captures the humanity of refugees living in the camp. Nahel put it best: “stories change people’s minds in a way that statistics don’t, so let’s tell these stories.” The Jungle not only makes us feel a part of the story, we also feel a sense of guilt and shame for the mistreatment of these people in the West – it’s a stark wake up call. But The Jungle also promises hope, sitting down as a black woman interviewing an amazing black woman actor in the West End is a true sign of progression in British theatre.

The Jungle is running at The Playhouse until November 3 2018. You can book tickets here.