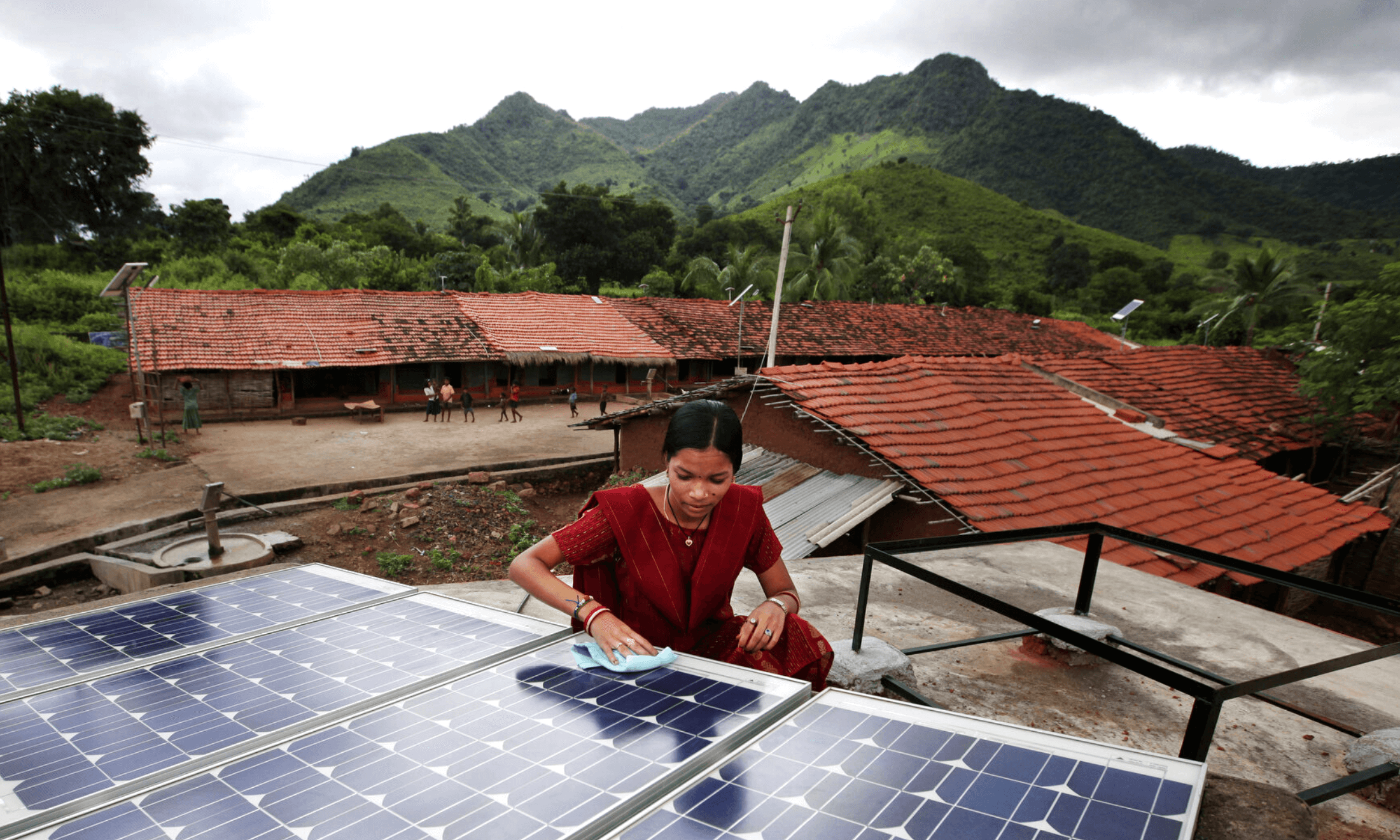

Image by Vinodh Pullot Chandrasekharan/Creative Commons

The pilgrimage to the historic Sabarimala temple, a shrine in Kerala dedicated to the Hindu god Ayyappan, has strict rules. Prior to visiting, devotees are expected to observe 41 days of ritual austerities, which include cold water baths, and forgoing meat, alcohol and sex. Tradition states that any person observant to these rules is admitted, except women and girls within the “menstruating” period of their lives. In September 2018 the Supreme Court ruled to lift this prohibition, but protesters set on upholding tradition have stopped all attempts by the Communist government of Kerala to let female devotees enter the site.

Growing up as a child in India with my devout Hindu grandmother, visiting temples was part of my daily routine. I was very familiar with the process: taking off your shoes, proceeding to admire the deity, making the rounds, and finally awaiting the smear of kumkuma on my forehead. Despite not sharing her uncompromising faith, I always did and continue to admire my grandmother’s dedication to religion. So, when I heard the Supreme Court ruling in September, that all women, regardless of age, could enter the famous Sabarimala temple in our neighbouring state of Kerala, I was quick to tell her the good news that we could finally visit together. I was met with a resolute no. My grandmother, much like 75% of people in Kerala, disagreed with the decision and saw it as an affront to her religious practice.

On New Year’s Day 2019, hundreds of thousands of women, led by the southern Indian state Kerala’s Communist government, formed a “women’s wall” – a human chain stretching over 625km from the northernmost point of the state, down to the state capital of Thiruvananthapuram in the south. This was followed by two female devotees, aided by police officers, entering the shrine. The response was weeks of violent protest between those supporting the right of women to enter the temple and Hindu fundamentalists, which has culminated in violence which has left many injured and at least one dead.

“Supporters of the ban claim to be defending a tradition associated with the temple’s mythology”

Supporters of the ban claim to be defending a tradition associated with the temple’s mythology. Various stories are told but the common thread is that the Hindu god Ayyappan, in his avatar as a prince, defeated a terrifying demoness at the spot of the shrine. The demoness, in turn, fell in love with Lord Ayyappan and asked him to marry her, but he refused, insisting that he would only marry her the day new devotees stopped coming to seek his blessings. This never happened. Instead, Lord Ayyappan stuck to his vow of all worldly desires, and in line with this spirit, women of menstruating age were not permitted to enter the temple for fear that they could “tempt” the deity.

This notion of women spurring the “sexual energy” of the deity or the male devotees, builds on a narrative of women as inherently manipulative temptresses and feeds into the culture of victim-shaming for those survivors of rape and sexual harassment. Rape myths create harmful narratives which suggest that what women were doing and wearing at the time of their assault provoked their attacker. This is certainly poignant for a country which is, like most around the world, plagued by the continued problem of gang rape and sexual harassment of women.

Many argue that is not the role of the Supreme court to make judgements about religious practice, but to the contrary, their job is to uphold the Constitution of India, which was made to represent an ideal India. In recent months, the Supreme court supported by the Constitution, dismantled several regressive colonial-era laws, including repealing a 157-year-old act that criminalised gay sex. In overturning this ban, the court proved its secular credentials and made clear in its judgement that “the right to practice religion is available to both men and women”, invalidating the discriminative myths and legends that pollute an ultimately progressive religion.

“This issue is not just one of gender, but reveals many of the fault lines fracturing Indian society”

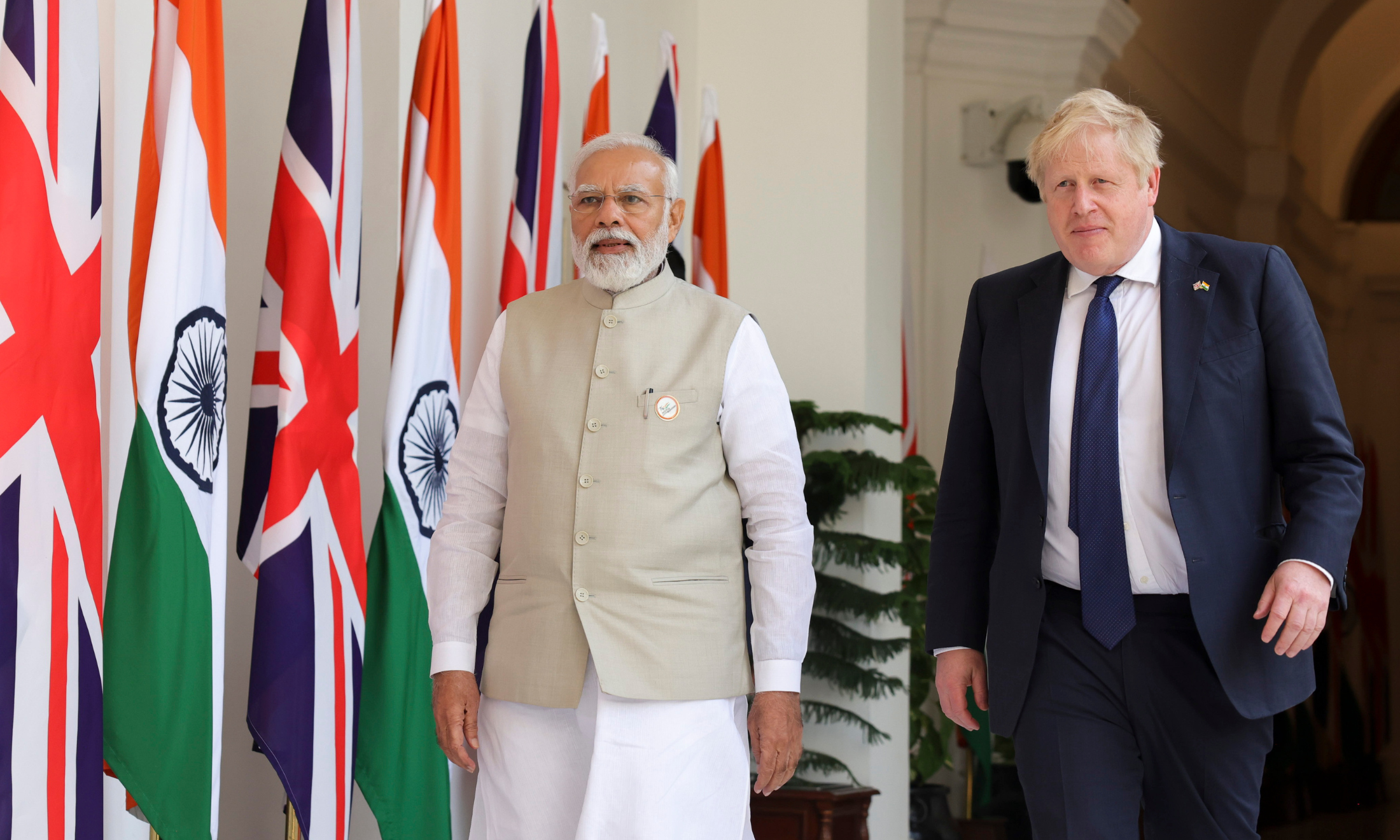

This issue is not just one of gender, but reveals many of the fault lines fracturing Indian society: between faith and politics, the government and the judiciary, and secular liberalism and religious populism. With elections just months away, both India’s biggest parties have chosen to seize the issue of “the right to practice religion” for political ends by denying support for the women’s constitutional right to enter a temple and subsequently bolstering Hindu nationalism. Narendra Modi, the Prime Minister, has said that the ban was a matter of religious belief, not gender equality. At the same time Modi supported the supreme court judgement outlawing triple talaq” – which allowed Muslim men to instantly end their marriages by saying “divorce” three times. This double standard is not only another blight for the Bharatiya Janata Party’s reputation on religious pluralism, but also exposes a ruling party willing to threaten the verdict of an independent judiciary.

For many, this issue comes down to the cornerstone of Hinduism, “bhakti” the sanctity of the unconditional love of the devotee, no matter what caste, gender or age they may be. To lift the ban would represent a precedential change for women in India. After all, every sphere of society, including the religious, should not be immune to change and evolution to align with prevailing standards. Surely, the supreme being, the one that my grandmother is proud to worship, would want Indian society to move towards embracing more tolerant and feminist principles?