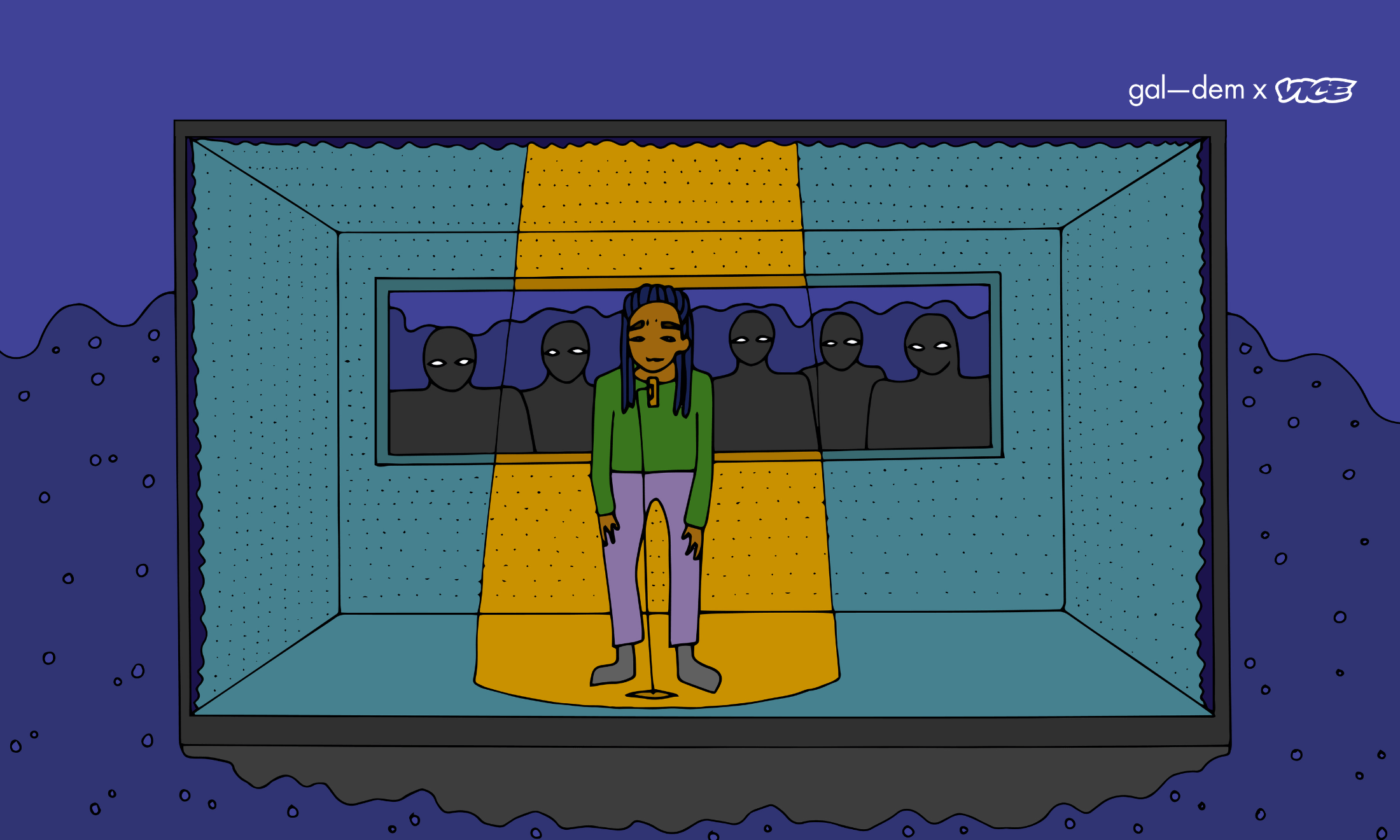

Image by Alice Jones

TW: This article contains graphic descriptions of sexual assault.

This article is taken from gal-dem’s latest print issue on the theme of secrets, available to buy now.

In the wake of the #MeToo movement, women around the world have come together to stand up against gender inequality and sexual harassment. The hashtag “#TimesUp” cropped up all over social media, with victims around the world condemning the treatment they have been forced to endure.

Traditionally, every evening, I discuss the daily news with my mother and sister whilst we have our “cuppa chai”. One thing my mother said regarding the #MeToo scandals was, “I thought only women from our cultures stayed silent. I guess shame is universal.” Her comment really irked me on many levels and for many reasons.

We can all agree that sexual harassment is physical, emotional and mental abuse, but more than that, it is an abuse of power. An act of dominance from the perpetrator and an act of (involuntary) submission from the victim.

Many questions have surfaced in the face of these stories: Why didn’t the victim speak up in the moment? Why has it taken so long to surface? Why didn’t the victim remove themselves from the situation? Why didn’t they defend themselves? Why didn’t they try to stop the situation from going further?

These questions infuriate me. They place the blame on the victim and don’t take the emotional or mental trauma associated with being a victim of abuse into account. My mum really hit the nail on the head when she spoke about shame. The feeling of shame and associated guilt is the pivotal reason why victims do not speak out.

I can relate to this. I know the shame and guilt I felt when I was a victim of abuse. I’ve suffered from sexual abuse countless times, from many different people since I was six years old. This is the one experience I have never been able to talk about. Even whilst I am writing this, I have a pit in my stomach, my heart is racing and my are hands clammy. It’s a story I’ve kept to myself for 16 years.

I was 13 years old when I went to Saudi Arabia to perform pilgrimage with my family. It was our first day in Mecca and we were performing Tawaf, the ritual of going around the Kaabah seven times. The nearer we got to the Kaabah, the more the crowd began to thicken and slow down. Suddenly, I felt someone pushing onto me. At first I thought it was an accident and a result of the vast, throbbing crowd. Then I felt someone grabbing onto me forcefully from behind, and a large hand swiftly entered my trousers, then my underwear, painfully forcing its way into my vagina while the other hand gripped my skinny frame so hard I couldn’t move.

The crowd was so dense, I felt completely trapped, both physically and mentally. In my mind, I felt so conflicted as it was a sacred place of worship and I wanted to remain respectful. I couldn’t summon the courage to scream or shout and instead I went numb and felt my whole body freeze. The hand stayed there and painfully kept thrusting in me with such force. I physically couldn’t move. What may have been a minute felt like hours of anguish. I desperately wanted it to end and to escape. The crowd jerked forward and with the force of the horde he was jolted away; I felt his grip loosen and the reluctant release of his hand. Subconsciously, I took this window of opportunity and crouched on to the floor in a bid to get lost in the crowd.

I felt something hot oozing out of my underwear, down my leg and along my shalwar. I could feel the heat of humiliation washing over me as I thought not only had I broken my wudhu (the ritual of cleaning and washing before prayer) but out of sheer fright I had urinated on holy ground.

I finally found my family and we completed our Umrah. The entire time I could feel the hot shame and guilt consume me. I wanted to get out of my body or swap it for a new one; I felt so dirty in my own skin. Part of me felt like it was a punishment from God for some sin I may have committed. As we prayed in front of the Kaabah, I remember staring up at God and thinking, “why did this happen to me? What did I do to deserve this pain and humiliation?” I was so ashamed and couldn’t help but feel like it was my fault somehow. After all, who gets assaulted in the house of God? The holiest, most revered place on Earth for millions of Muslims all over the world.

I felt so dirty and disgraced that I couldn’t even cry and, to this day, I never have. I was too embarrassed to tell anyone out of fear that someone would judge me, say it was my fault or, worse, tell me I deserved it. It’s the one place on Earth where, as a Muslim, you would hope to feel safe and protected. Yet for me, it was a place where I was violated.

For a long time I was angry at God, but looking back now, I realise my anger was misguided. I’m angry at society and our culture of encouraging women to stay silent and save “honour”. Where we make it okay for women to feel ashamed and guilty for something that isn’t their fault and we force them to carry these burdens silently.

I wish I could say this was the only instance where I was assaulted, but it was not. I graduated from university and started working at a prominent global financial news company in London. My job involved daily meetings with senior executives in finance and prominent owners of hedge funds and investment firms. Their names appear in the Sunday Times Rich List and are regularly splattered across the Financial Times. Advances were made towards me on an almost weekly basis, including unsolicited groping and forcing their hands on my body, including up my skirt and on my bum. I received inappropriate sexual text messages and was even grabbed in the office lifts whilst being “walked out”.

After a while, I finally had enough and built up the courage to tell my senior manager. I narrated the stories to her and as a fellow woman, I thought she would really have my back. Instead, she said, “well you’re tall and pretty – what do you expect?”

I walked away from that meeting feeling like I had when I was 13. Ashamed, guilty, stupid, embarrassed and dirty. I felt that, somehow, it was my fault. That perhaps I’d encouraged the assault. I recounted a story to a good friend of mine who, at the time, was a journalist at The Sun. I told him some of the names of the men who had assaulted me. He laughed and said, “Nosh, they will always get away with it. No point you running this story – you’ll destroy any chance of having a career in finance.” The sad thing about what he said was that it was true.

Looking back all these years, I wish I could have done things differently. I wish I could have screamed during Tawaf and pointed the creep out. I wish every time I was in a private meeting room I could have slapped the culprits and walked out. Like many of the #MeToo women, I too stayed silent. I too felt ashamed, felt guilty, felt embarrassed, and felt like it was a man’s world and I had no place or say in it.

I used to think that the notion of honour and staying silent was a by-product of centuries-old patriarchy in the East. The unspoken understanding that women are subordinate and second-class citizens to their male counterparts is something that is so deeply entrenched in our society. Double standards have become the norm and they go largely unchallenged. I used to think, like my mother said, that it’s just women from our cultures who stay silent or feel ashamed, but as more and more stories pour out of Hollywood, I’ve realised that’s not the truth.

What’s clear is that, regardless of culture, we women have been marginalised. But our time is coming. No longer will we stay quiet. No longer will we be compliant with what a patriarchal society deems appropriate. No longer will we be marginalised or sidelined. Our time is here and I look forward to the day when we no longer have to say #MeToo.