Illustration by Mariel Richards

Exactly a decade ago, I started high school in the suburbs of southern Virginia. The beginning of 9th grade wasn’t particularly extraordinary, but it signified new responsibilities, harder classes, and more studying – much to the satisfaction of my Indian parents.

But aged 14, I was blindsided by a strange phenomenon occurring at school.

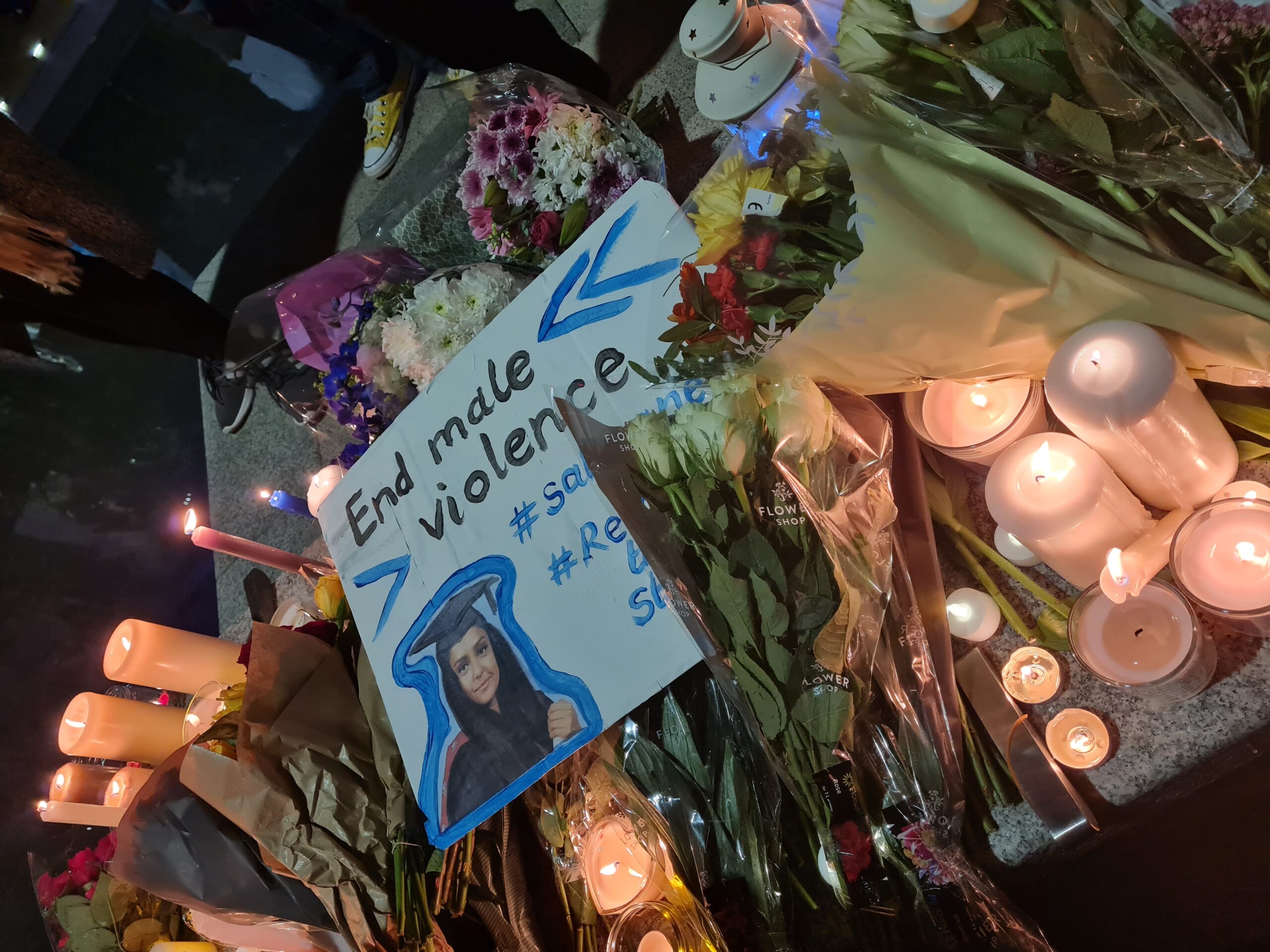

“What the POOJA?” several teenage boys cackled through the hallways.

Let me backtrack. In the spring of 1995, my parents battled over the perfect name for their second daughter. Archana? Sanjana? Monica? All of these names were on the table. Finally, my father picked out a short, yet powerful name: Pooja. Pooja is a form of prayer in Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism. The name is derived from the Sanskrit word “pūjā”, meaning honour or worship. The name is sacred and symbolises devotion.

Aside from the majestic meaning, let’s be real. “Pooja” is also the “Becky” of Indian names. If you’re South Asian, the chances you’ve met a girl named Pooja are very high. This wasn’t the case in the small town I grew up in, however, where only a handful of South Asians resided. As well as the childish allusions to “poo”, those around me met my name with distaste. As soon as I recited my name, I would notice a look of confusion cross people’s faces. Their expression inquired, “Why would your parents name you that?”

“Their expression inquired, ‘Why would your parents name you that?’“

Suddenly, my name became an ad hoc expletive. “What the Pooja is going on?!” my peers laughed in class, or “How the Pooja did this happen?” they would question mockingly. The desecration of my name expanded and rapidly became a huge inside joke amongst the boys of my high school. Instead of trying to understand the cultural significance of my name, they used ignorance as a coping mechanism for unfamiliarity. Some of them didn’t even know me, they just knew of a 5’11”, dark-skinned, frizzy-haired Indian girl who happened to be different from those around her. She was unique, and that was the ultimate fuel to the fire.

As an Indian-American, many of us have faced some form of ridicule growing up in the United States. When people asked me if I was upset by the misuse of my name, I merely shrugged it off. At the time, I had internalised this type of derision and felt general apathy towards the whole situation. At least my name was in their mouths, right? Perhaps this pseudo-popularity was something to be proud of.

In the fall of 2009, our 9th grade class was introduced to one of the most infamous traditions of American high schools: homecoming. A homecoming dance and court were established for the festivities at my school. A representative from our 9th grade class was to be nominated to the homecoming court, and usually this was awarded to a blonde, “popular”, and athletic Caucasian girl. I didn’t fit any of these descriptors, but 2009 proved to be a different year.

By this point, the buzz around my name had garnered extreme popularity. As a result, my classmates decided to nominate me to homecoming court as a joke. When I made the shortlist, I was shocked. When I ultimately won the position, I was speechless. I remember hearing my name announced on the speaker system for the whole school to hear, as a sudden pang of embarrassment struck through my body. In that moment, I prayed for invisibility. I fended off questions from teachers and peers regarding my sudden ascent to the spotlight with feigned indifference. In reality, I was confused. Deep down, although I wouldn’t admit it, I was hurt.

“I had to stand in front of the whole school while the teacher announced my name. I felt so much shame as my fellow classmates laughed at me”

I remember the dismayed stares from “popular” kids at my school who were annoyed that I had somehow wiggled my way into their sacred homecoming court. For them, this was their territory, and I was an outcast. This delineation was made extremely apparent during an assembly, where I had to stand in front of the whole school while the teacher announced my name to the court. I felt so much shame as my fellow classmates laughed at me. After the assembly, I ran to the bathroom where I hid until all the students had left the school. I stared at myself in the mirror as a single tear fell from my eye, wondering what had gotten me here.

For years after, I pretended the whole incident never happened. I moved on. But every now and then, the events of my 9th grade year would creep back up in my memory and I could feel the same heat on my face as I did when I ran to hide.

What pained me most was the subtlety of it all. This wasn’t blatant racism: no one attacked me, no one called me derogatory slurs, and no one outright bullied me. But I was made to feel like an outsider due to my name, one who was erroneously given the opportunity to join a space typically reserved for white-Americans.

Names are such a big part of our identities: before, during, and after life. Prior to our actual birth, the first questions about us are what our name is going to be and in death, we are remembered by this title. Regardless of race, a person’s name holds an intimate significance. Some are named after an elder as a sign of respect, others take their namesake from a famed author or actor.

“This wasn’t blatant racism: no one attacked me, no one called me derogatory slurs. But I was made to feel like an outsider”

As women of colour, we are ascribed names that beautifully reflect our parents’ heritage and background. In western society, however, these names hold a cultural weight that rarely benefits us. This often leads to the erasure or whitewashing of ethnic names. In my case, my name was weaponised against me.

As a woman of colour, these incidents shape you and cause you to wonder. Are we supposed to be superhuman? Are we supposed to pretend this is what comes with being a different colour, a different ethnicity? Is it our burden to ignore the inequities we face and pretend everything is okay? Do we humbly accept our fate?

I will not anymore.

In reality, the society we live in is not set up for women of colour to succeed, especially those who are the daughters of immigrants. We are told to stay in our lane, not to make a scene, and to follow the paths that have already been paved for us by our previous generation. As a South Asian woman, I am speaking up against this racial hegemony. The apathy from my younger days has been replaced by ambition for change. I will continue to advocate for agency.

Ten years ago, I was involuntary propelled into a position that was not created for people like me. I now intentionally enter these spaces with the determination to change the narrative surrounding women of colour. We are not one size fits all. We come in different forms, with different backgrounds, and with different personalities that add perspective, culture, and insight into the ideas and tasks we contribute.

And in case you’re wondering: I love my name.