Since September, the upscale James Cohan gallery in New York’s Chinatown has hosted an exhibition exploring – wait for it – the gentrification of New York’s Chinatown. As part of Berlin-based artist Omer Fast’s exhibition August, the street view of the gallery has assumed a stripped-down, dilapidated façade mirroring that of a closed-down Chinese business, following a questionable tradition of upscale businesses exploiting lower-class aesthetics for profit. A description of Fast’s exhibition observes that in the interior, an “authentic Chinese business begins with an entryway displaying makeshift debris, a damaged awning, and graffiti-defaced walls”, complete with “defunct ATMs taped over with makeshift ‘Out of Order’ signs, overflowing trash bins, and a broken patchwork of a floor” in the interior. The move has sparked condemnation by New York-based Chinese community groups, who have issued a statement speaking out against what they see to be Fast’s reduction of vibrant community life to “poverty porn”, which gives credence to the idea of Chinatown as a “wasteland ripe for investment and exploitation”.

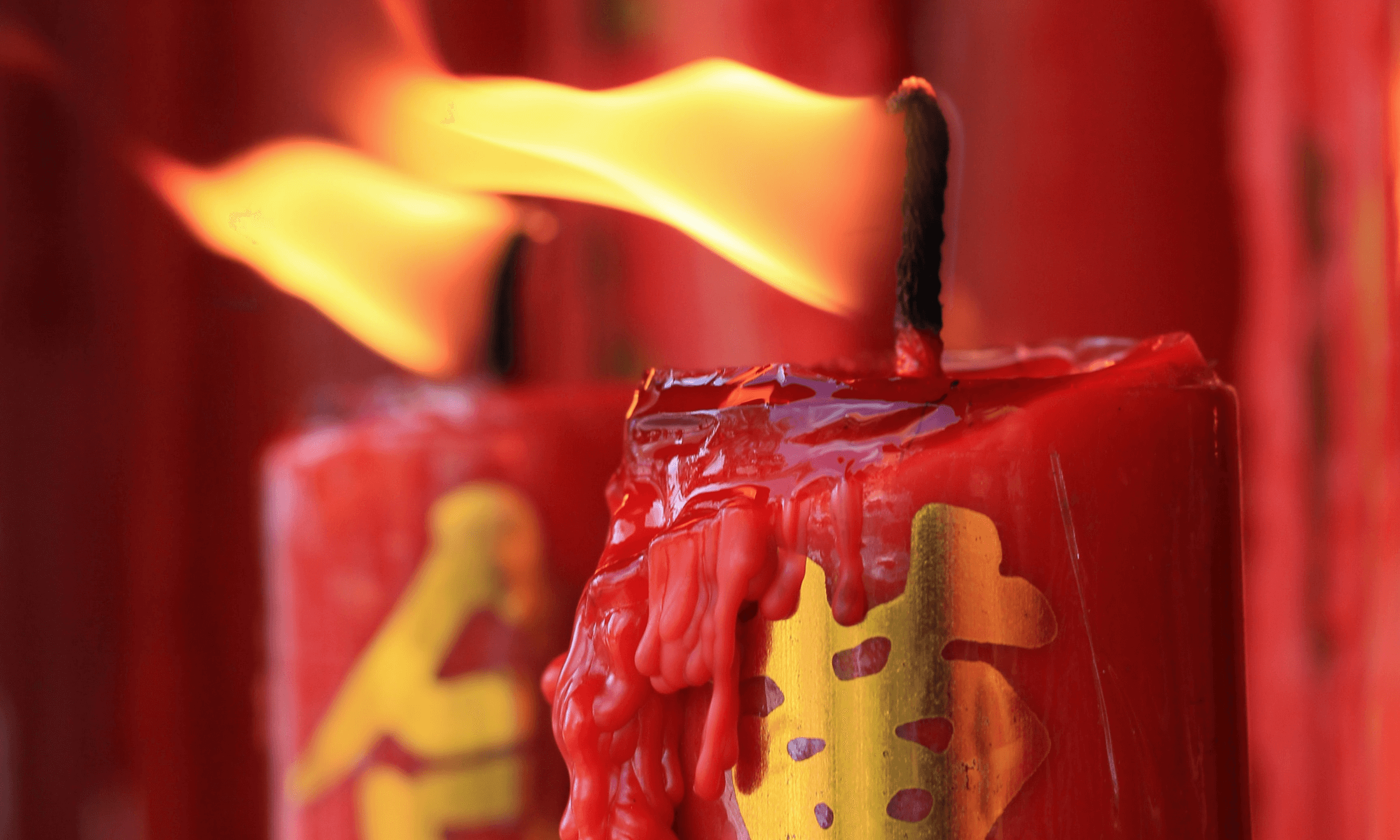

This isn’t the first time that New York art scene has seen a questionable homage to China as a site of cultural and artistic inspiration. The annual Costume Institute exhibition at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2015 explored China: Through the Looking Glass, with the intention of exploring “the impact of Chinese aesthetics on Western fashion [and] how China has fuelled the fashionable imagination for centuries”.

*

I visited the MET’s exhibition in the summer of 2015, and – in spite of myself – had looked forward to it. I had my reservations, of course: a quick look at Western cultural history, after all, calls into question its ability to be a sensitive and thoughtful arbiter of difference. But maybe this exhibition would be different. It did say from the outset that it was not an exploration of “Chineseness” per se, but an overview of how China has been seen “from the West”, thus candidly admitting its own biases. A review of the exhibition by Chinese-American fashion writer Connie Huang observes to some surprise that it was, on the whole “thoughtful, respectful, and fairly thorough”; the exhibition “is not about China, Chinese fashion, or Chinese fashion designers, and the Met makes that point very clear. Rather, it’s about how the West has borrowed from China throughout history”.

While I do not suggest that Huang and my opinions speak for all Chinese purveyors of the exhibition, my experience at the MET largely aligns with hers. Aside from placards that celebrated the positive “creative energy” of this cultural exchange, as if to paint the history of Chinese-Western relations to be a sanitised dynamic between two equally powerful and consenting powers, I found the exhibition to be an educational and sensorially rich exploration into the ways in which the spectre of Orientalism, while bearing little resemblance to actual Chinese life, has shaped the Western cultural imagination.

“I remember thinking in those halls: is this the pinnacle of cultural conversation that art can offer?”

And yet, I remember thinking in those halls: is this the pinnacle of cultural conversation that art can offer? Even while the MET spoke of Orientalism as a product of a vibrant inter-cultural exchange, what I saw was a sterilised, one-sided portrayal on how one culture regarded the legacy of another with very little attempt to take the conversation further. Designs from modern Chinese designers were few and far between. The voice of China, in the exhibition, was largely signified by pre-modern pots, earthenware, paintings, taken up and interpreted by the modernising Western eye. For an exhibition that wanted to celebrate the artistic and cultural legacy offered by China, there was remarkably little effort exerted to imagination any genuine Chinese counterpart.

“Art that unreflexively portrays ‘culture’ through pre-existing tropes that are familiar, staid, and fossilised into tradition, fails to create any new and interesting dialogue about the meaning of culture.”

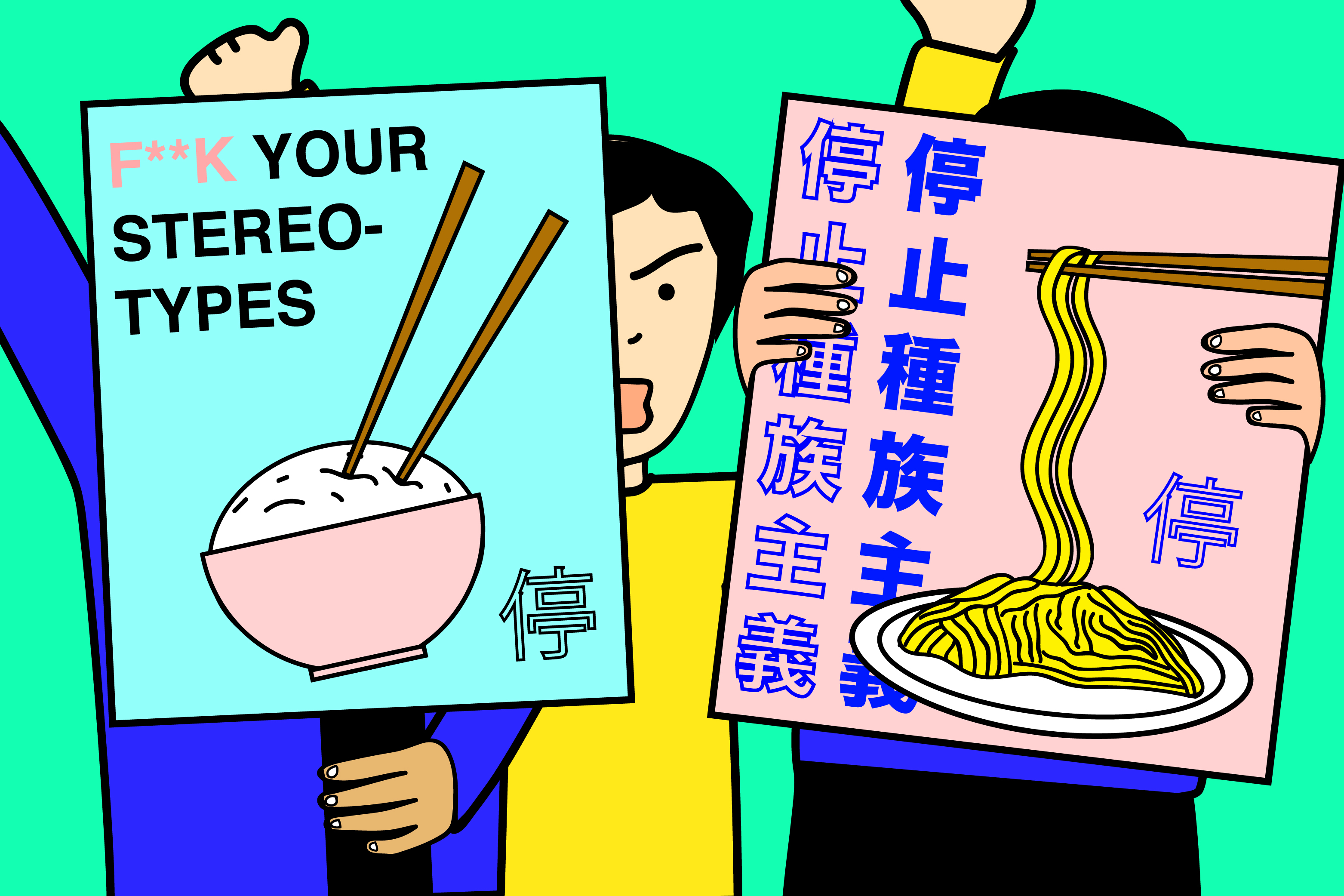

That art should be channelled to bring cultures together and interrogate their boundaries is often an argument marshalled in favour of activities commonly charged with appropriation. Novelist Lionel Shriver of We Need to Talk about Kevin fame famously railed against what she saw to be “identity politics gone wild” at the Brisbane Writers Festival last year, adorned in a symbolic sombrero to assert the right of novelists to “assume many hats” in their writing. Continuing its tradition of grating iconoclasm, the New York Times Opinion section recently published a column titled ‘Three Cheers for Cultural Appropriation’, in which columnist Bari Weiss railed against “an increasingly strident left […] careering us toward a wan existence in which we are all forced to remain in the ethnic and racial lanes assigned to us by accident of our birth”.

Shriver and Weiss are right, but not in the way they may think. Art is valuable in that it allows its maker to assume many hats as possible, and, by doing so, discover hidden power dynamics and truths underlying the human condition. To assume, from the position of privileged New York punditry, the “hat” of a frustrated, working-class, black teenager, long sanctioned and mocked for her dialect or manners of dress, only to see her white counterparts thrive on exploiting these very same signifiers. To assume, as a curator at the MET, the “hat” of an 19th century Chinese official, who struggles with the impossible task of leading a nation that keeps falling closer and closer to the clutches of its English opium-traffickers. To assume the position of a 21-year-old Chinese woman standing at the exhibition’s gates in 2015, wondering why Western engagement with her culture extends only as far as to assert the West’s ultimate status as the true movers of modernity; the Tang-dynasty pots, and tapestries of her forbearers merely become “exotic” miscellany relegated to a pure prehistoric footnote.

“Art is valuable in that it allows its maker to assume many hats as possible, and, by doing so, discover hidden power dynamics and truths underlying the human condition.”

Empathy cannot be a one-sided demand. By this, I mean Shriver and Weiss must recognise a privilege that exists. A productive cultural exchange requires those in power to critically interrogate their position as the primary beneficiaries of a shared history.

*

Taking us back to Omer Fast, perhaps the more pointed charge against his art is not that it’s merely scandalous, but that it is, at its very core, deeply mediocre. If the task of art is to assume as many hats as possible to unseat dominant narratives and introduce new ways of seeing, art that unreflexively portrays ‘culture’ through pre-existing tropes that are familiar, staid, and fossilised into tradition, fails to create any new and interesting dialogue about the meaning of culture. It becomes an exercise on communicating familiar symbols that reproduce the very systems of power it claims to critique. Rather than offering any novel critical commentary on the state of cultural relations, art often delivered from this position becomes merely another case study in how ‘Westernness’, with its privileges, can furnish what is an ultimately boring, conceptually dry depictions of Otherness into some claim to meaningful artistry. At least the MET had the foresight to admit that it explored “Chineseness” from the perspective of a largely white, Western lens; Omer Fast’s work doesn’t even take that first step.