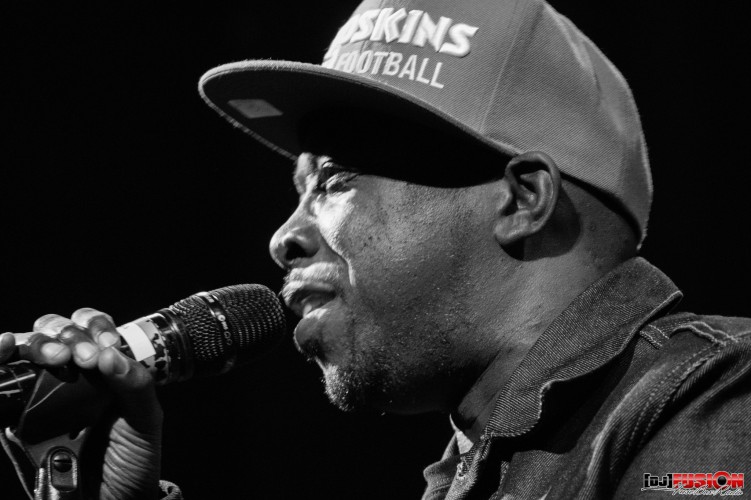

Today the world learned of the death of A Tribe Called Quest’s front man Phife Dwag, at the tender age of 45. After forming the group in 1985 with fellow classmates, Q-Tip, Ali Shaheed Muhammad and Jarobi White, A Tribe Called Quest stormed into the East Coast scene. Revered and loved the world over, his death was an unfortunate reminder of the state of the black man in America.

Like many other African-American men in America, he suffered from diabetes. Section 8 housing, and a severe lack of educational resources and opportunities plagued the black community and consequently contributed to the early death of many black men before him. But A Tribe Called Quest’s arrival in 1990 couldn’t have been timed more perfectly. Pioneering alternative hip-hop in the East Coast, a movement began that would stick a middle finger up to Reagan’s Jim Crow style policies.

As a result, the state of black consciousness was in disrepair. The sentiment of the ‘black is beautiful’ campaigns started in the 60s still hung in the air, ever present but unreachable. The collective Native Tongues was the solution. Their positive Afro-centric lyrics utilised the pain of earlier jazz and reformed it with extensive use of eclectic Afro-futuristic samples. Serving as a connection to African heritage and reaffirming black identity, they brought topical issues to the spotlight.

But despite receiving critical praise and featuring tracks such as ‘Rhythm (Devoted to the Art of Moving Butts)’ and ‘Description of a Fool’, People Instinctive Travel and the Paths of Rhythm failed to break into the mainstream. The message contained within the lyrics of ‘Description of a Fool’ rang true for every black male. The war on drugs, racial attacks and police brutality were crippling the black soul and, with a shift back to colonial mentality, the black woman was also under attack. ‘Who would love a woman / turn round and abuse her’ was a fight back against the state of their fellow sisters and a way for the entire black community to connect for a progressive cause.

Hip-hop at the early 90s was at a junction. The lyrics of Public Enemy and NWA had actualised. But A Tribe Called Quest remained hopeful of a black resurgence. They were unafraid of, and unapologetic about, proclaiming their heritage. Each album asserted and defined their consciousness. Every album released in the 90s from People Instinctive Travel and the Paths of Rhythm to Beats, Rhymes and Life paid homage to their African ancestry. Each cover explored either the urban landscape that African-Americans were confined to, the black body or surreal interpretations of modern life using the colours of African flags.

It wasn’t until the video release of ‘Can I Kick It’ that young black men could express themselves in the same way their white peers had. Black identity and youth expression was no longer confined within the limits white America had set. A Tribe Called Quest’s look was immediately adopted. People were unafraid of mixing traditional kente cloth with Jordans or wearing dashikis or shaving their hair in distinguishable geometric patterns. It was a time of unadulterated expression and a moment of relief.

As we revel in nostalgia by singing to ‘Scenario’, we remember Phife Dawg’s contribution to healing of the black community.