Canva composite of press photos / Creative Commons photos

Is our obsession with queering the likes of Harry Styles costing LGBTQI+ artists of colour?

Where does the framing of artists like Taylor Swift as queer icons leave queer POC in music? Zoya Raza-Sheikh explores how the UK music scene has been complicit in upholding white success as a default standard.

Zoya Raza-Sheikh

27 Feb 2021

Speculating over an artist’s sexuality is nothing new – in fact, it’s pretty common. You may have read about the days where the media fawned over who Freddie Mercury was dating or widely guessed at the blossoming relationship between Whitney Houston and her assistant. Today, the lens has shifted towards high-profile white, supposedly straight, artists that flood charts and queer subcultures – Taylor Swift, Harry Styles and Bad Bunny are emblematic of this.

Since the vengeful, gothic era of Reputation, Swift’s persona has careened from emotive black and white pop to an explosively vibrant canvas of glittering rainbows embedded into a fictitious universe. Detailed with pastel cobblestones and the campiest dance numbers I’ve seen in a while, fans were eager to search for symbolic meanings. Her music videos, ‘Delicate’, ‘ME!’, ‘You Need To Calm Down’, ‘Look What You Made Me Do’, were packed with easter eggs and specific lyricism that gave way to wild romantic suggestions and re-ignited the fire behind every Kaylor/Gaylor conspiracist – aka stans that are convinced Taylor is either secretly closeted or once had a fleeting romance with model Karlie Kloss.

Harry Styles has fallen into a similar rhythm in benefitting from a sexually ambiguous image that piqued mainstream interest after the release of the “bisexual anthem” ‘Medicine’. The lyrics (“The boys and girls are in / I mess around with him / I’m okay with it”) were enough to convince flocks of fans that Styles was confirming the fluidity of his sexuality.

“It’s not about solidarity with queer communities or standing in their own identity – it’s just another part of marketing”

Kindness

At the same time, take someone like Bad Bunny – he describes himself as both white and straight, but has been praised with terms like “queer icon” for dressing ambiguously and drawing attention to LGBTQI+ activist causes. As André Wheeler wrote for the Guardian last year, “It becomes obvious there is more capital to be gained from wearing the queer activism of the moment like a costume than actually living and embodying it. If Bunny really wanted to dispel homophobia within reggaeton music, he would use his large platform to feature the queer and trans artists that are frequently silenced and ignored within the genre.”

This culture of queerbaiting hasn’t gone unnoticed and producer, artist and DJ Adam Bainbridge (Kindness) breaks down how the appropriation of queer aestheticism is an industry-wide issue. “It’s not about solidarity with queer communities or standing in their own identity – it’s just another part of marketing. If Harry Styles is bi that’s great, Harry Styles should just say that,” they say over Zoom. “We can see there is no significant homophobia experienced by white male superstars at this point. It’s not going to affect his career, is not going to affect his fan base – if anything, it’ll probably improve all of that, but it would take away a huge amount of the desired tension within his sort of long-term marketing just to say: ‘I’m bisexual.’”

To be clear, whether it’s theories forced on the One Direction boys or speculation surrounding Luke Hemmings from 5 Seconds of Summer, no artist has to come out. Coming out takes full commitment and can have immediate repercussions that can’t be seen by an outsider looking in. The problem lies in those appropriating queer culture and aestheticism for profit, cultural elevation, and general benefit. Of course, people are allowed to explore their sexuality, but the issue, for me, lies in when it moves from personal change to industry gains.

Harry Styles can be as frivolous as he likes with his clothing choices, but when queerness becomes ingrained in your personal brand to such an extent you’ll take a bisexual role in an upcoming film or become marked as a trailblazer for queer acceptance, you have to understand the indignation. The line between being out and profiting from queer aestheticism is a tight one. We shouldn’t encourage an industry where artists must be out before they’re ready, but neither can we celebrate a culture that allows purposefully ambiguous individuals to profit off of a queer demographic while Black and POC artists who are out and proud are extremely unlikely to find a place in the mainstream.

“Harry Styles gets to play around with gender, and it’s considered progressive and groundbreaking, but trans people don’t get any kind of grace when it comes to moving beyond the gender binary”

Iqra

Iqra, 26, who identifies as bisexual, also agrees that white, cis, hetero artists are given a luxury with gender and sexuality that most queer people of colour aren’t afforded. “It’s this idea that queerness is profitable and it feels like it’s a very unfair playing field,” she explains. “Harry Styles gets to play around with gender, and it’s considered progressive and groundbreaking, but trans people don’t get any kind of grace when it comes to moving beyond the gender binary. If you’re someone who is straight or hasn’t come out as being queer, the ambiguity is not only fine, but it’s profitable because then you can appeal to queer fans without ever having to explicitly come out.”

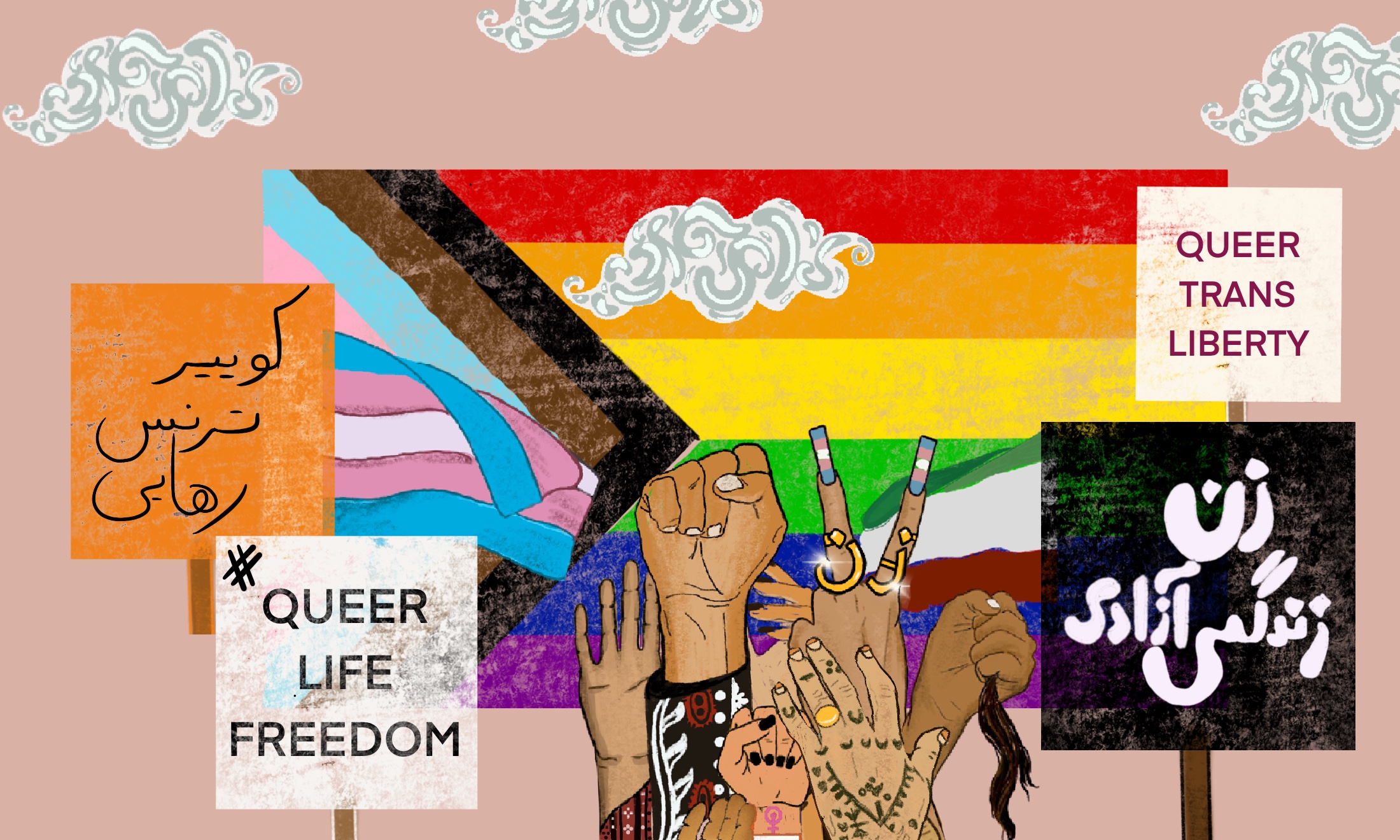

As artists like Harry Styles and Bad Bunny continue to carve out a presence for themselves in the queer community, my frustration in the cultural repercussions has peaked. Intentional or not, the rabid queering of white straight musicians (who are not currently out) undercuts an array of queer musicians that own their sexuality and openly present themselves. The likes of Rina Sawayama, Chika, Shamir, Raveena, Dua Saleh, Omar Apollo and Hayley Kiyoko are painfully unrecognised for their contributions to queer art.

Instead, we see a wave of cis, hetero artists benefitting from queerness being perceived as a quirky tag-on which moulds a very real aspect of personal identity into a marketable “queer brand” gimmick. And still, there’s an unexplained fascination around a white straight man who could possibly be gay. Let’s be real, did the internet really care about Shawn Mendes until there was a chance he had a boyfriend?

“Of course, people are allowed to explore their sexuality, but the issue lies in when it moves from personal change to industry gains”

Unsuprisingly, both Mendes and Styles have weaved their way into the playlists of queer listeners where queer subtext has become a talking point rather than a valid, genuine aspect of identity. This bias and attachment to making white men “spicy” doesn’t end here either. A quick glance between Harry Styles’ and Lil Nas X’s Twitter page speaks volumes. Sure, Styles has been around longer, but the treatment and reception to both are massively diverse. Lil Nas X has had to countlessly defend and clarify his position on his sexuality, while Styles has faced little to no retribution for his murky, sexually fluid image. The whitewashing of the LGBTQI+ community is not uncommon, but the presumption of its normative state being white is.

Even take someone like Katy Perry who, while she is LGBTQI+ identifying, is afforded more grace than her Black and brown counterparts. ‘I Kissed A Girl’ may have been dragged online (and later called out for its questionable lyrics), but Perry continued on with a massive pop star career relatively unscathed. She can ultimately present her sexuality with little to no professional repercussions.

The casual acceptance of white artists being able to delve in and out of queerness without question or account is hard to dismiss.

Timi, who identifies as bisexual, finds the double standard exhausting. “Ariana Grande has done it as well. In ‘Monopoly’ with Victoria Monet, Ariana sings ‘I like women and men’, but hasn’t mentioned her sexuality since,” she says. “These artists dance around it. They’re appealing to our demographic by engaging in these aesthetics, which is really unfair for them to insert themselves into spaces that they actually don’t want to occupy […] it’s allowed because they’re white, cis-gendered, and conventionally attractive. It allows them to throw up all of these identities and move within different spaces with ease, without it ever affecting their career.”

“The casual acceptance of white, supposedly queer artists, being able to delve in and out of queerness without question or account is hard to dismiss”

Adam recalls a Guardian interview where Matt Healy of The 1975 admits, mid-interview, that he flirts with queer aestheticism. “Matt Healy has been clearly Islamophobic, clearly transphobic, has a history of being obnoxious on Twitter, but certain white artists are just untouchable, especially by the UK music press.”

This speaks to the structures that exist in UK music journalism. “What happened to the politicisation and radicality of queer culture that someone can admit to doing these things and not be asked a follow-up question?”, Adam asks. We discuss another piece written by The Guardian, and they reflect on how they felt when their pronouns remained unused in the write-up: “If all of the writers in positions of power in the UK are white and cishet, this kind of bullshit keeps going and there is no criticality.”

Across all industries, including music, we still see a lingering bias towards white representation, whether it be latching onto Harry Styles or the white cis gay male majority eagerly accepting white cis women (Britney Spears, Kylie, Madonna) as gay icons. The suitable place of race in the queer community and queer music industry is one that remains to be answered. Should queer women of colour have to continually appeal to the white male gaze in their audience to hit the queer mainstream? There is an LGBTQI+ hierarchy that’s a reminder of how power and control within communities can be distributed. Although you can’t force a queer icon if the majority of an audience’s taste lies angled towards a white icon, can we be surprised when artists such as Tyler, the Creator or Frank Ocean, who are widely acclaimed, become examples of how only a handful of QPOC artists are adopted into the mainstream?

“We’re ultimately privileging whiteness to be the defining cultural lens through which everything is consumed,” Adam says. They recall watching the concept play out when they were on the Popjustice forum. “I quickly noticed how certain gay culture fetishises white women and upholds them as a kind of monarchy of pop music at the expense of everyone else. It’s got misogynistic undertones towards the idolatry of women within cis, male gay spaces.

“If all of the writers in positions of power in the UK are white and cishet, this kind of bullshit keeps going and there is no criticality”

Kindness

“There’s something about how white gay men can relate to white, straight women that becomes even more toxic when it’s white gay men interacting with Black and brown women. There’s a certain amount of self-identification here,” they explain. “White men identify with other white people, and there’s a certain universality e.g. ‘I could imagine myself as a Britney or Madonna or a Kylie’ […] Unfortunately, the consumption is really reductive in the way that Black and brown women are often used in gay culture.”

White cis gay men, to a large extent, have historically been the face of – and thus controlled the iconography attached to – the LGBTQI+ community in the UK. As they often seek to see themselves in similar white cis-hetero women artists, the inclusion and acceptance of QPOC artists will remain stunted, othered and flattened into “fierce” stereotypes until the queer community, as a whole, becomes more inclusive.

So, while the return of Taylor Swift’s reign might have offered some mid-pandemic relief, the online queering of her work has given way to a cultural issue it’s hard to overlook. folklore and evermore have subconsciously slipped into lesbian cottagecore territory where queer theories and conspiracy theories have surfaced over flipped narratives, an artistic fickleness with penned pronouns, and creative interpretation over winter-heavy outfits.

Don’t get me wrong, I like to indulge in my fair share of literary interpretations, but when audiences start splitting hairs at what qualifies as “queer love” and begin questioning which artists legitimise its meaning, it stems directly back into an active oversight of the queer experience — one which is neither exclusively white, tragic, or as an aesthetic. In speculating over Taylor, Harry Styles and more, the queer mainstream continues to ignore existing, queer POC artists.

So, while I’d like to claim myself as #teamBetty, or a 1975 stan, for now I don’t think I can.