Photography courtesy of Manchester Central Library

“You know, sometimes I wish I was a fella,” says 87-year-old Elouise Edwards laughing. “Look at you three beauties!” Her eyes brighten as I approach her hospital bed in the Manchester Royal Infirmary with my mother and aunt.

She’s plucky but frail, shrinking into the propped up blue mattress as a result of the chemotherapy she’s undergoing to fight cancer, a tough treatment to undergo in your twilight years, but with an impressive history of black activism, much of her life can be characterised by courageous resistance. Elouise is one of the few surviving women who was at the forefront of a push for equality in Manchester for the new Windrush arrivals and their children.

The sheer amount of projects her name has been attached to has led me on a meandering journey to her hospital ward with the permission of her son, Mark Edwards. I’d travelled to my hometown to uncover some hidden black history. It’s rare that the northern city’s name is mentioned in the same breath as blackness given that it is much whiter than London. Almost 84% of Mancunians are white, compared to just under 70%in the capital according to the last census. But still, Manchester is home to almost 30,000 black people.

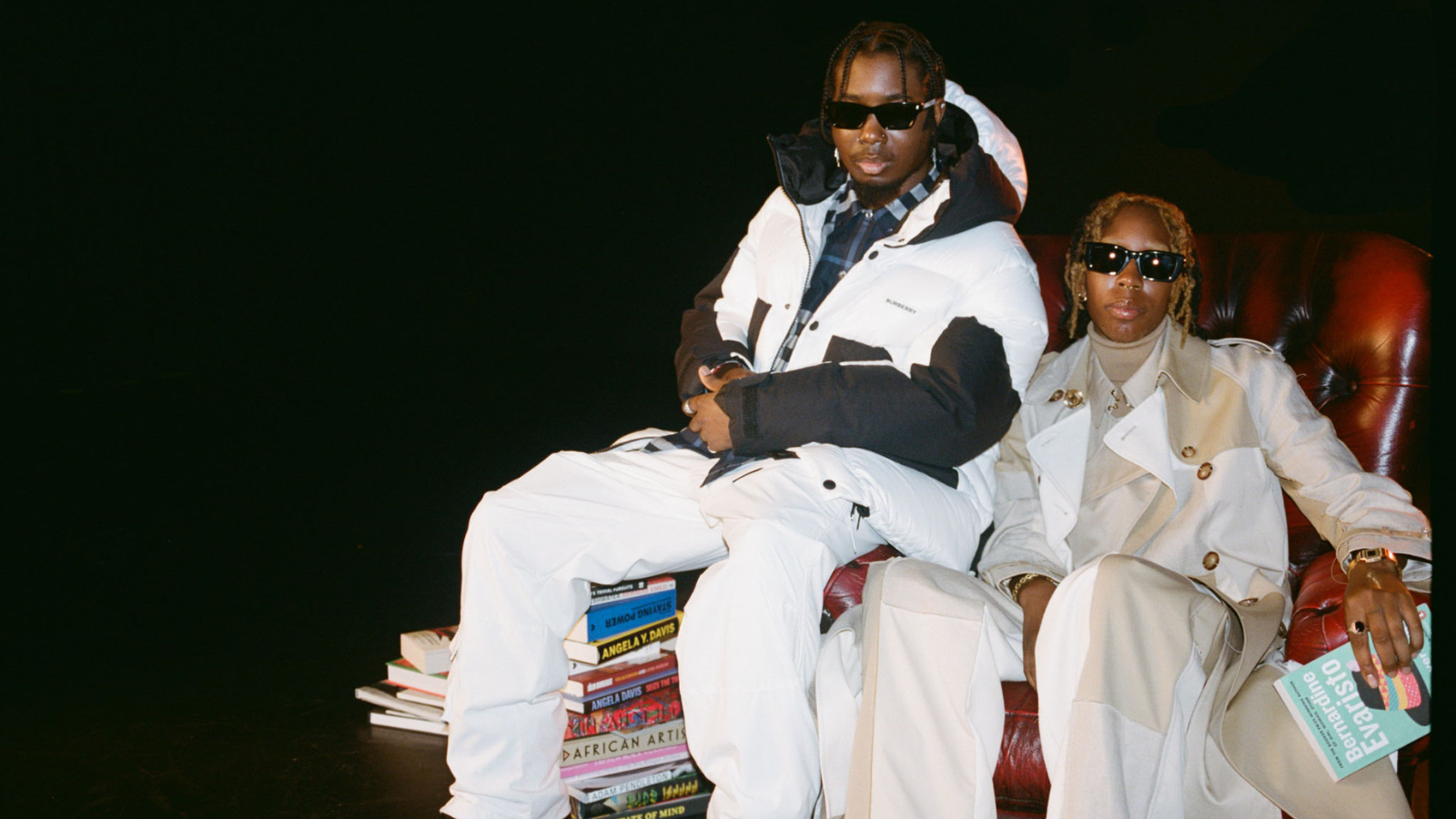

For the younger generation, not much is known about the unique struggles, or notable community leaders that came before us at a time when there was a “colour bar” in full force across employment, housing, and education. My education on race relations in school had focussed almost entirely on American civil rights or slavery. But to fill in the crucial gaps to find out about black women’s roles in Manchester’s black power movement I have to look beyond GCSE textbooks – and even beyond Google.

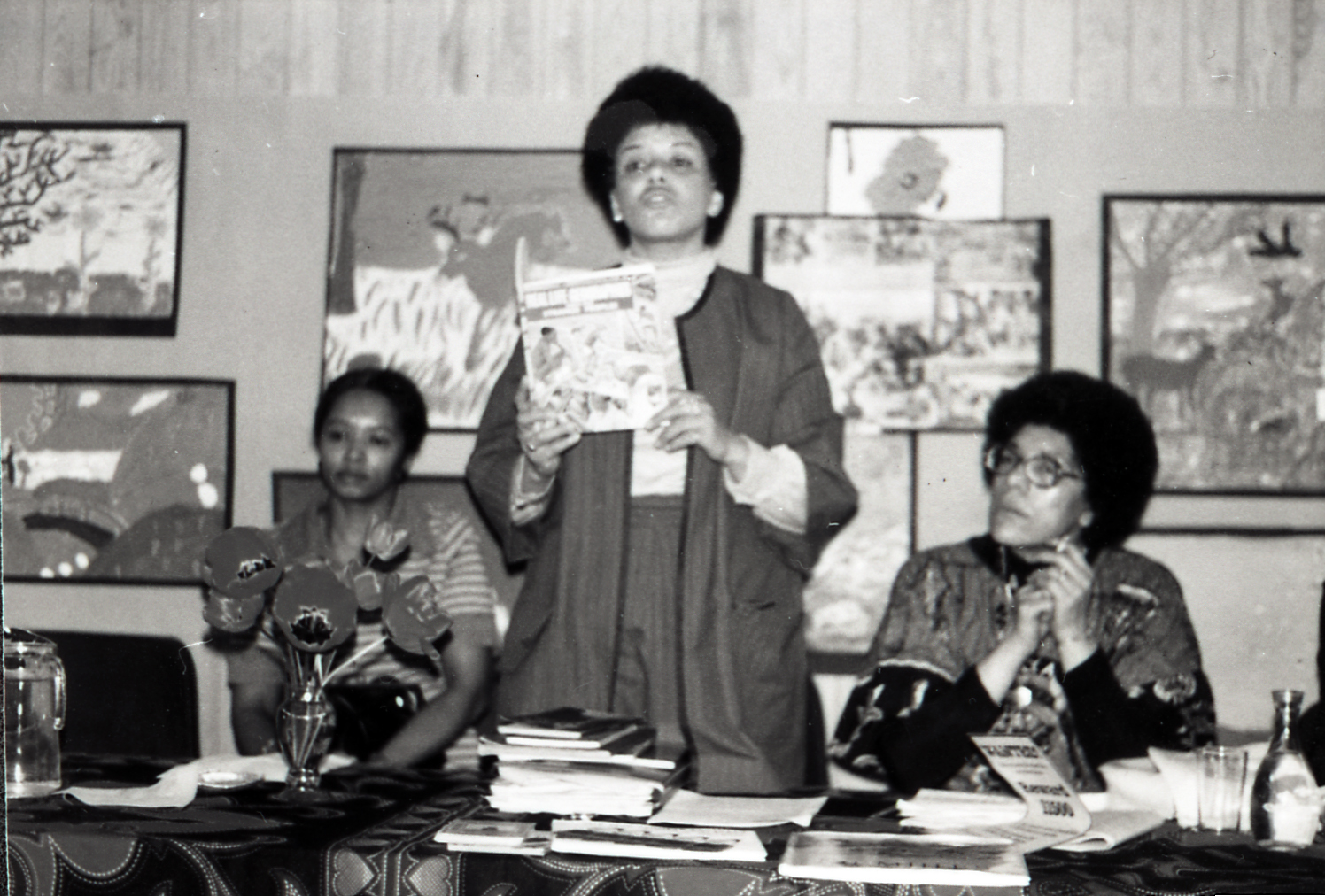

(From left to right) C. Robinson, Dorothy Kuya, and Kath Locke at a women’s conference organised by Black Women’s Mutual Aid at Princess Road Junior School in 1975, courtesy of Manchester Central Library

Instead, I dig through the archives inside the Manchester Central Library, a grand, Grade II listed building made of white stone. I arrive in Manchester to be greeted by the city’s dull, near-constant smattering of drizzle. What I learn in the library is a testament that details which for some might feel almost too regular or boring to note can be the vehicle to gaining a whole new level of understanding for others. Because when I told my older family members what I found, previously forgotten memories started bubbling to the surface.

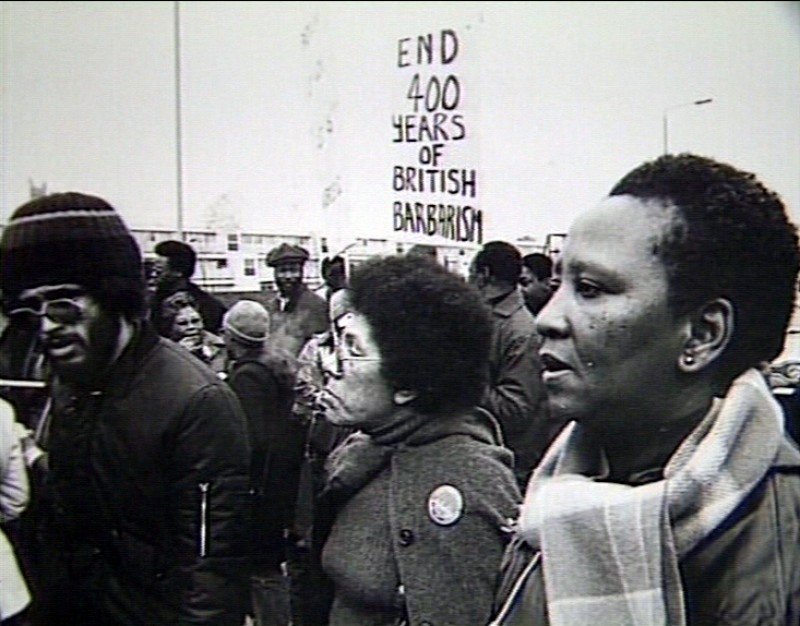

Magnifying glass in hand I peek into a bygone era via some deposited black and white photographs. Passionate black women faces framed by afros, all running grassroots campaigns out of premises in Moss Side and the neighbouring areas.

“We had such a rich history but I only wish we’d had a day off!”

Elouise Edwards

In one photo: there’s Olive Morris, hailing from St Catherine, Jamaica. She was brutally humiliated by police in London and went on to join the Black Panther movement. While she studied up north for university she set up the Manchester Black Women’s Co-operative and the Black Women’s Mutual Aid Group which worked to lobby for better treatment of black children in education. She used squatting as activism and repurposed the spaces as bases for political organising. She did all of this before she died at just 27 of Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma.

Another photo depicts a familiar name: Kath Locke, the namesake of a centre I visited in the summer as a child which provides childcare, mental health support, and even needle exchange. Yet I was completely unaware of her back story, and to find anything about her takes serious digging. In a biographical film made about her by Paul Okojie, she said she was motivated to devote her life to community organising because when looking at black populations across the world, she “saw that we [were] always at the bottom”. As such she’d started the Abasindi Co-operative to support black women in Manchester alongside Elouise.

I leaf through the photos, noting names scrawled in the margins: C. Robinson, Dorothy Kuya, Ada Phillips, Mimi Tsele, Joan Brown, Vivien Morse, Barbara Duncan, the list goes on. When I describe the images to Elouise she smiles. I’d gone through such a lengthy process to find her, and most of these photographs and documents were submitted to the library by Elouise herself and they chronicle the life she has led so that future generations could understand what came before. “It’s so important that you remember that you’re part of a line of people who elevated this country,” she explains.

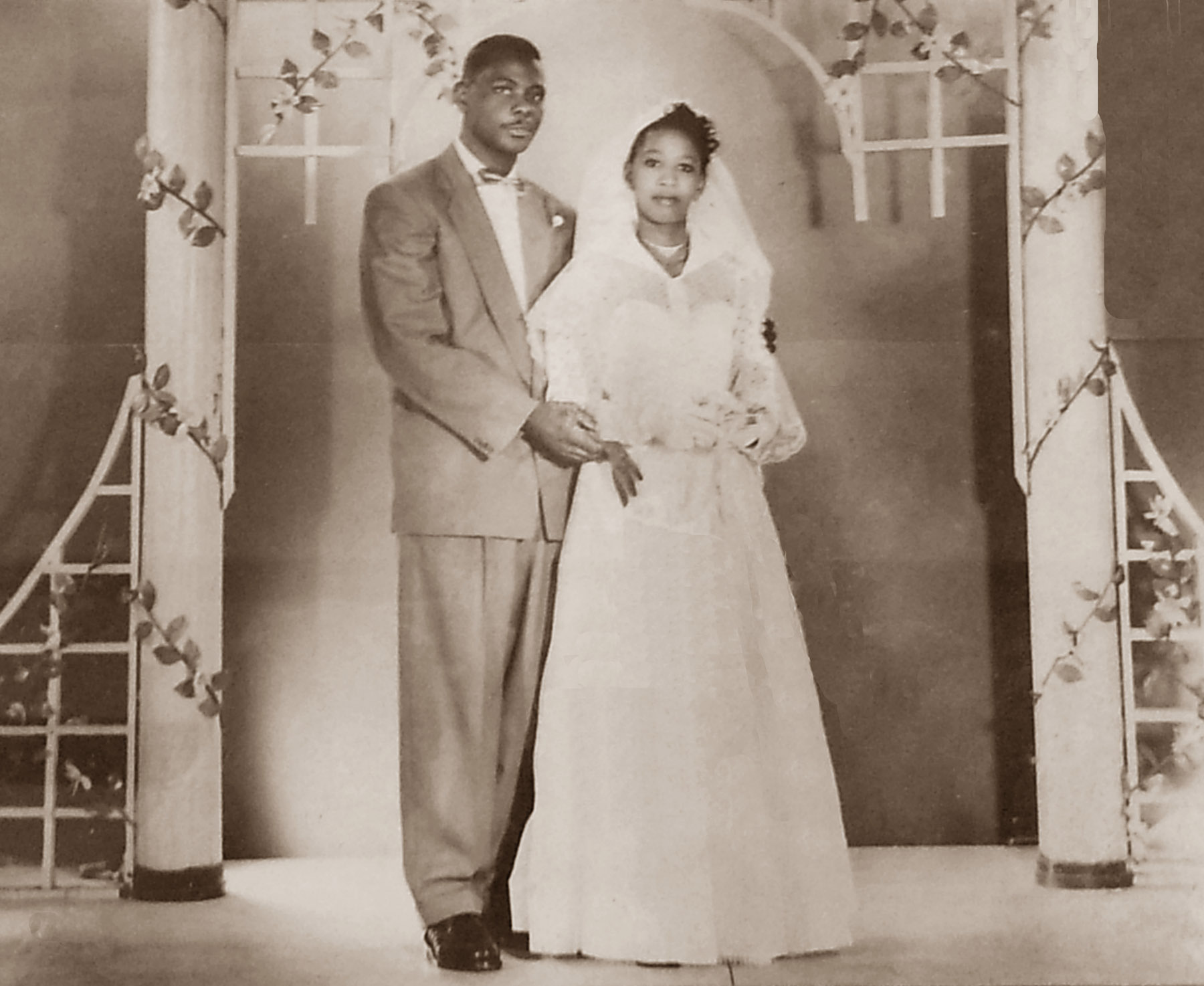

One image in the library shows her juggling (her son Mark tells me that she “loves” juggling and was still able to do very recently before becoming ill). This still was taken on the boat over from Guyana in 1961 when she first came to England to join her husband Beresford. Despite her cheerful exterior Elouise really wasn’t a fan. She’d been well off back home. “Samuel Hubert Chandler, my father, was a gold digger. He dug gold through the whole country. We brought so much wealth to Guyana.”

She admitted in an interview to accompany her submissions to the archive that England fared badly in comparison. “I never wanted to come. Mr. Edwards wanted to, he was a printer and he wanted to study lithography. So he came over first and then I followed but it was never my intention to leave home. I was very, very unhappy when I came here.”

They settled in Moss Side using a partner (paadna/ susu) scheme as it was impossible to get a bank loan or mortgage if you were black. Over the years her house would become a meeting place where black people would come to talk through issues facing the community. Especially after 1964 when she and Beresford co-founded the West Indian Organisations Coordinating Committee (WIOCC) to unite communities from all the islands which was and still is based on Carmoor Road. She says she did so to “improve things” for their children. Three years later her husband sued his trade union when he was fired for missed fees because of an administrative error while other white workers who’d experienced the same thing remained working. He won £7,971. His was a landmark case that showed both of them the power of resistance.

Among her other projects was the Arawak Housing Association which helped the black community in Manchester find good quality homes. Knowing that young people in her community were under tremendous pressure which was impacting their wellbeing, she then kick-started the African Caribbean Mental Health Project and offered solace and care via the Family Advice Centre in Moss Side. On top of all this, she was also the chair of the Nia centre in 1990 which became a cultural hub for afro-centric drama, music, and dance. “We had such a rich history but I only wish we’d had a day off!” she laughs.

Beresford had strong links to Marcus Garvey, who impressed on him the importance of taking pride in our history and traditions. In the 1970s Elouise took on his mantra that “a people without the knowledge of their past history, origin and culture is like a tree without roots”. Many of her projects centred on connecting people with the cultures they had lost. Elouise started Yoruba language classes to encourage Caribbeans to learn what could once have been their mother tongue as she felt it was important to “learn our forebearer’s languages”.

She also started the Roots festival dedicated to racial harmony and would explore a new theme each year. For example, in 1988 she kickstarted the Roots Family History Project, which archived people’s lived experiences in their homelands and how they settled into England. It’s an amazingly detailed resource of minority families committing the local POC community’s lives to paper. Eventually, she donated the findings to the University of Manchester for research purposes along with almost 1,000 photographs, newspaper clippings, black newsletters and more.

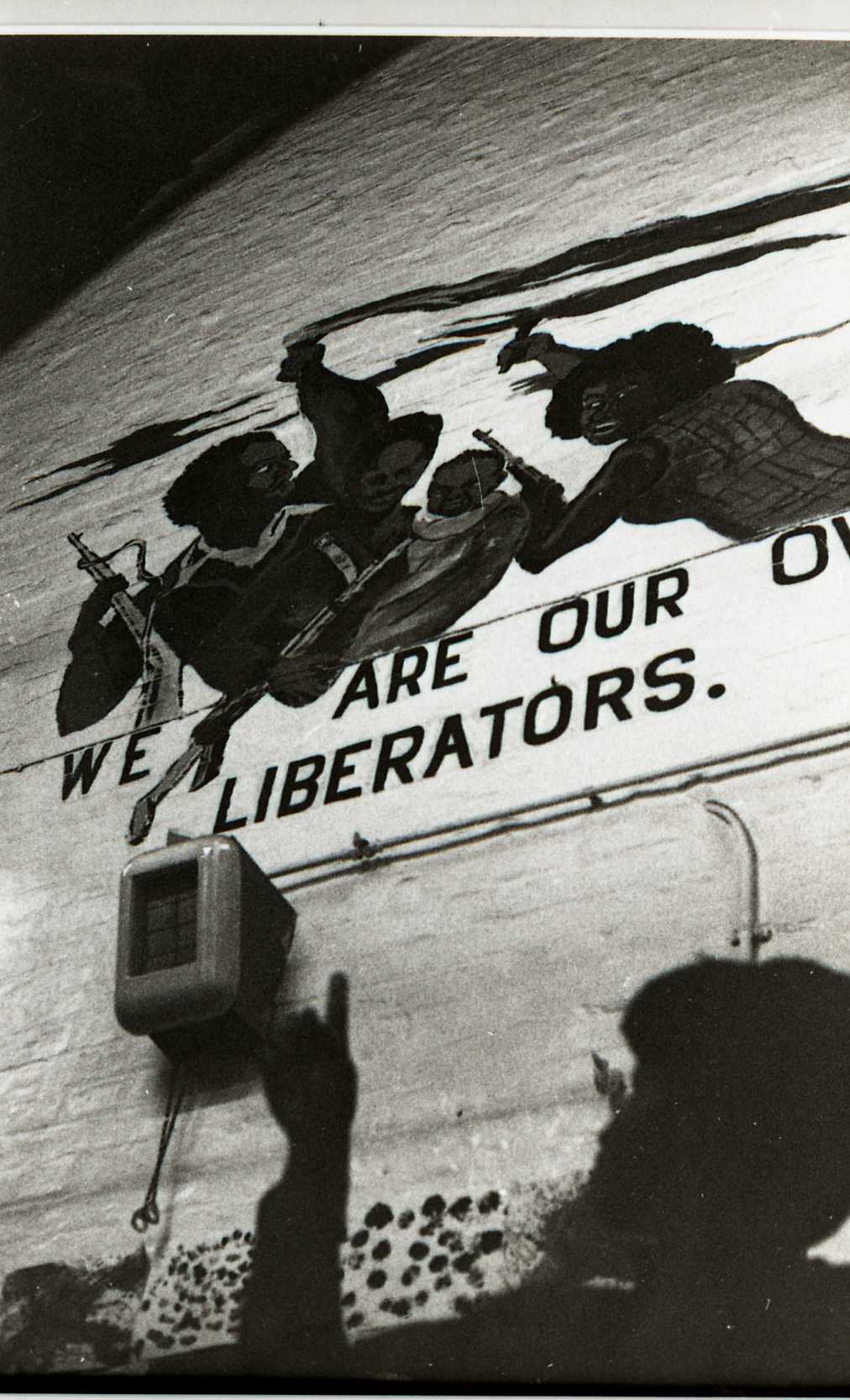

Most heartening was how Elouise and her cohort created spaces for her community to find each other, improve their wellbeing, and celebrate each other. Having wanted to find an example of black feminist action in Manchester what struck me most was the Abasindi centre which Kath and Elouise set up. In 1980, they felt some other women’s spaces had become too dominated by men and the state and that in order to effectively meet their needs black women needed full control. In response, they occupied St Mary’s School for 10 days and nights and repurposed the space.

“It’s so important that you remember that you’re part of a line of people who elevated this country”

Elouise Edwards

Abasindi was volunteer-led and the income they got was from providing affordable services like hair plaiting and selling traditional African clothing, jewellery, and crafts. It also acted as a drop-in space for the elderly, a play centre for children, a place to address health concerns like Sickle Cell, and a supplementary school teaching children English, Maths. Later cam Abasindi Cultural Theatre Workshop (ACULT) to develop the local Afro-Caribbean performing arts in dancing, singing, playwriting and poetry.

During the 1981 riots, as Moss Side burned and boiled over with violence in response to police harassment and black youth unemployment (people with a Moss Side postcode felt discriminated against when applying for jobs), Elouise even opened Abasindi as a makeshift hospital.

In 2011 she told Manchester Evening News: “It was a terrible time. It was so frightening. One young white lad came in, he had been beaten up. He was an apprentice baker just coming home from his job, he didn’t know what was going on. We took him to the hospital because his injuries were too big for us. We could have left him on the street – and he said something that has stuck with me forever. He said, ‘But you were the people they taught us to hate’.”

Given that Moss Side was once home to famous suffragette Emmaline Pankhurst, it is fitting that I discovered it was the epicentre of black feminism in the city. However considering the intersectionality and ferocity of her pursuits, Elouise deserves to be remembered as one of Manchester’s most radical women. For the last five decades, she’s been instrumental in developing community resources in an area of Manchester that has been long maligned. She was awarded an MBE for her amazing contribution in 1994 for services to the community in Manchester.

“We are part of a ruling class, we’re part of a people who came to help this country grow,” she says to me recounting her experience of being honoured by Prince Charles after a lifetime of service. And, even dearer to her heart is the African chieftaincy that ceremoniously renamed her and her husband to Mama Edwards and Nana Bonsu as what endears her is the culture of “respect” among her own people.

“I’m so glad that you’ve come to see me – I’d almost forgotten it,” she says. I hold her hand to thank her for all the work she did that meant that paved the way for my generation to experience Manchester in a whole new light. “Don’t let it go. Be proud of it. These things they will last in your memories for years to come,” she says before gritting her teeth. “Keep it alive.”