This article is part of a series exploring the films that make up Unbound: Visions of the Black Feminine season at the BFI. As part of the season, gal-dem is hosting a day of short films and discussion. Tickets for Daughters of the Dust and the full programme can be found here.

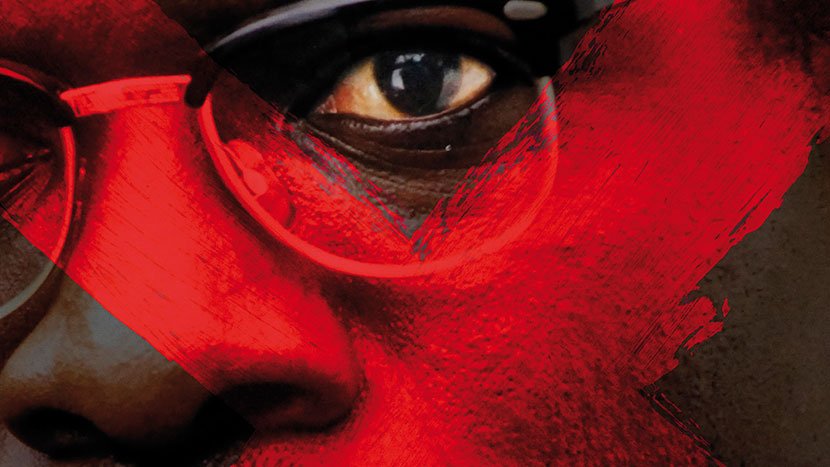

The cinematic re-release of Julie Dash’s 1991 film Daughters of the Dust could not be timelier. The film’s portrayal of three generations of Gullah women (descendants of West African slaves) at the turn of the 20th century is uncomfortable, encouraging and visually stunning. Arthur Jafa’s cinematography is embellished with olive green palm trees toasted by fiery sunsets, the browns of this all-black cast, and a southern gothic aesthetic as re-imagined in Beyoncé’s visual album, Lemonade.

Despite a running time of nearly two hours and a dialogue that is deliberately difficult, we are won by John Barnes’ mystical score and the devout expression of family, and African culture retained through isolation. The story unfolds around the Peazant family’s contemplation of their decision to leave their land and legacy at Ibo Landing for the North-American mainland. Here, Julie Dash explores such themes as feminism, religion, and race; the eerie normalcy of the mistreatment of black women, the affection for our cultures, the reverence of our mothers, or the tug between authenticity and being “civilised”. Many of us, through experience, will identify with the matriarch Nana Peazant’s fear that the North will not be “the land of milk and honey” the others anticipate.

Initially, I was irked by the use of the island and the Gullah’s isolation as cornerstones for this unencumbered blackness motif. A part of the Peazant family is scared shitless that moving to America will erase their culture, some fantasise of this estrangement, one retreats from the north for refuge in the island’s traditions, and the rest decide never to leave, to “keep the old ways”. This all screamed fragility to me. I was defiant that black culture was not that flippant.

Later I realised the real crisis was that I believed that culture was retained by some automatic osmotic process. I was reminded that culture will be prised and preserved, or be spent. In fact the isolation came to impress on me the importance that the notion of the supremacy of Western hegemony be contained. It was like a clear uninterrupted thought. It was like being reluctantly left at some foreign aunt’s house only to eventually return home and question why exactly you do things the way you do here. Why you never put olive oil on your salad.

Egotistically I loved that the film was centred on black women. I loved even more that although there were archetypes there were no stereotypes. I loved most Nana Peazant’s statement, “the older I get the closer I get to the ground”.

I am grateful for “Daughters of the Dust” in the way that I am grateful for “Get Out”, and “Moonlight”. These insist that my self-confidences – loving my afro, eating fufu with my hands (there is no other way), thinking Giggs is or will be a classic in the same vein as Mozart, taking offence when I’m sometimes perceived as less black for being educated – are poetic rather than political or deviant. Above all, the film is a celebration of unencumbered blackness in all its embodiments, from art, to speech, to hair, down to food.