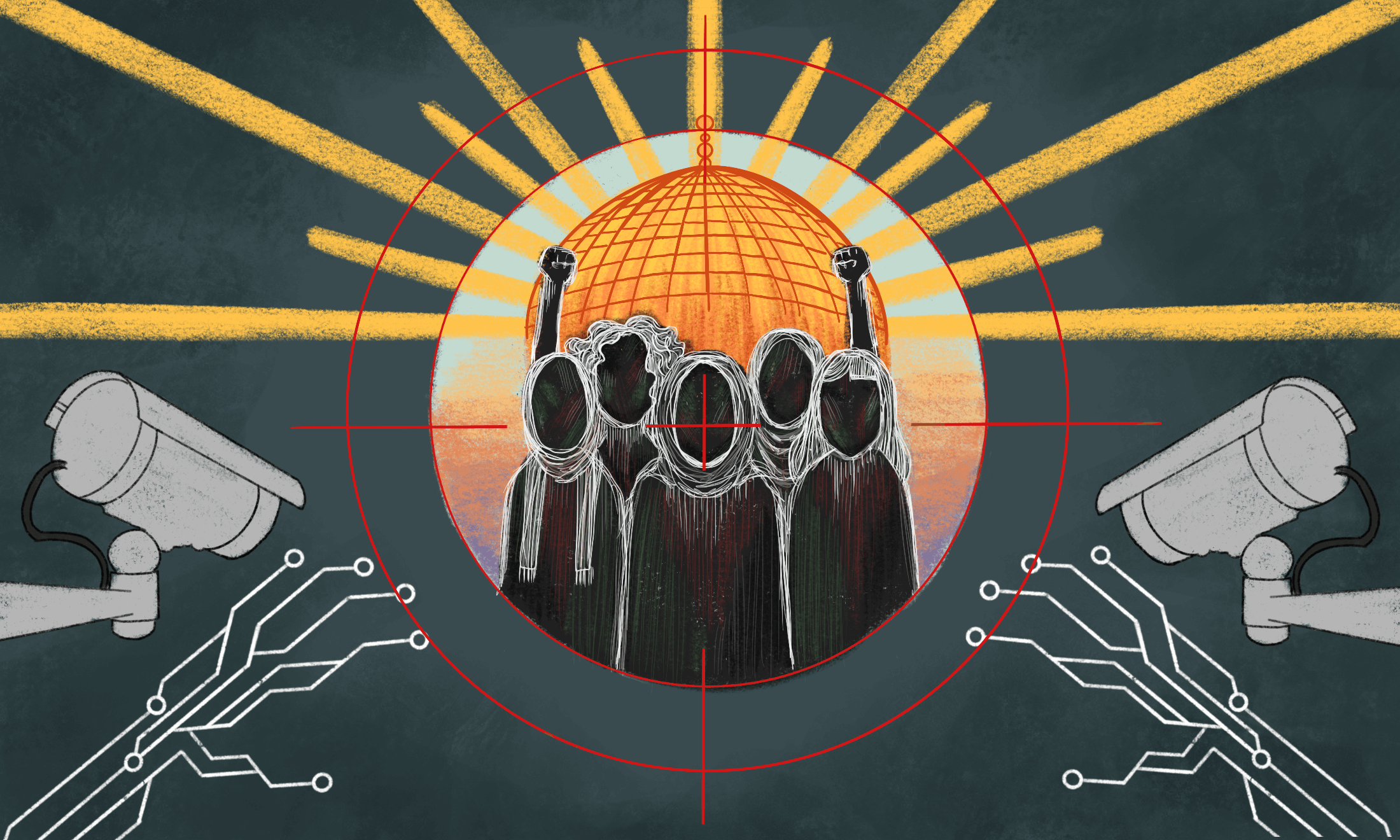

‘The border crossed us’: why Rashida Tlaib and Ilhan Omar are banned from visiting Israel

Sara Mohtaseb

21 Aug 2019

Image via Wikimedia Commons/Kristie Boyd; U.S. House Office of Photography/United States Congress

“What is your brother’s name? What does he do? Is he married? What is your sister’s name? What does she do? Is she married? What is your other brother’s name? What does he do? Is he married? What is your mother’s name? Where was she born? What is your father’s name? Where was he born?”

This stream of questions was launched at me when I was interrogated at the Tel Aviv Ben Gurion Airport a few years ago. Reading about the Israeli government’s decision to ban Democrat Congresswomen Rashida Tlaib and Ilhan Omar from entering the country last week took me back to my own experience.

There is a lot left unspoken when you’re a Palestinian being held and questioned at the Israeli border. For instance, it’s not articulated, but the reason you’re being selected for interrogation is very evident. As soon as you are taken aside to the waiting room – where the majority of those being held are Palestinians or Arabs, or black or brown people – the common thread quickly becomes apparent.

This does also mean that there is a level of camaraderie between those being held for questioning: people share food, swap drinks and make jokes to pass the time. When I was held at the airport, a North African man shared a sandwich with me at 2am – sustenance I was grateful for, as I had been detained for seven hours at that point and hadn’t eaten since before my flight had left London. I was able to repay the favour later by translating for him when he was also denied entry, and joined me at the nearby immigration removal centre.

Crucially, the reason that we are denied entry and banned from entering Israel at all is also unspoken. After I returned to London, once I’d paid a lawyer to ask questions about what had happened to me, I was given an assortment of formal reasons for being denied entry. These reasons included variously: I didn’t have enough money for my stay (I had more than enough); I cried too much for attention, and I wouldn’t hand over my phone so that they could go through my messages and contacts (remember, there are no civil liberties at the border). The words “it’s because you’re Palestinian” were never used.

“Our relationship to Palestine and our heritage is a way for us to hold out for the ability to return to the country”

They didn’t need to be. Israel’s ongoing project of ethnic cleansing – through land grabs, house demolitions, settlement expansions and bombings of Gaza – includes attempts at disrupting the relationships of Palestinians in the diaspora to Palestine. Our relationship to Palestine and our heritage is a way for us to hold out for the ability to return to the country. It is a way of having hope for freedom for Palestine – and to show that Palestinians cannot be erased.

Make no mistake: the British government does know why I and other Palestinian Brits have been denied entry. Information on the Foreign & Commonwealth Office (FCO) website which gives information on travel to Israel explicitly states:

“If you are a British national with a Palestinian name or place of birth but without a Palestinian ID number, you may face problems. A number of British nationals of Palestinian origin or British nationals married to Palestinians have been refused entry to the country.”

When I reached out to the FCO and asked for support, I received a curt response saying that they couldn’t and wouldn’t offer me anything. According to the FCO, what happens at the border of another state is not their business. The UK has a vested interest in this mutual non-interference remaining the case so that they too can detain and deport whoever they like. In short, the UK government won’t defend my rights because it wants to be free to violate the rights of others.

“Ilhan Omar and Rashida Tlaib are joining a club of hundreds of thousands of people who are banned or blocked from entering Israel”

Ilhan Omar and Rashida Tlaib are joining a club of hundreds of thousands of people, if not more, who are banned or blocked from entering Israel. It is unsurprising that the Israeli government and President Trump are happy to work together to ban two high profile US politicians from being able to enter the country. After all, Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu did name a new settlement in the occupied Golan Heights ‘Trump Heights’ as a gesture of gratitude for Trump’s decision to recognise Israeli sovereignty over the Syrian land.

Alongside a packed programme of visits and meetings with different groups and individuals, Tlaib had intended to visit her ageing grandmother who lives in the Palestinian village of Beit Ur al-Fauqa in the West Bank. What is being ignored in all of the media coverage and discussion over the ban, however, is a simple explanation of the fact that in order to travel to the West Bank, whatever route you choose to take it is necessary to travel through Israel-imposed borders. This can be through Tel-Aviv Ben Gurion Airport, or via Jordan where you can cross over the three different bridges: King Hussein/Allenby, Wadi Araba/Yitzhak Rabin, or Sheikh Hussein/Jordan River. Israel has total control.

When people question how I have previously travelled to Palestine, and I tell them that I’ve flown there, they often respond “Oh, I didn’t know it was possible to fly to Palestine!”. This is a frustrating, but understandable response. It isn’t possible to fly to what we now recognise as Palestine – those tiny overcrowded slivers of land known to the rest of the world as the Occupied Palestinian Territories (made up of the West Bank and Gaza). Despite the West Bank being permitted by Israel to have their own elected authorities, it’s still under military occupation by them. Gaza itself has been under siege for over 10 years.

“To visit Palestine we must travel through Israeli ports and be permitted entry by the very state that cleansed and displaced our families from their homes”

For those of us who hold relationships with Palestine that extend beyond the creation of the state of Israel in 1948 (my father was born and displaced from a city that now sits within Israeli borders), and for those who have loved ones there – it’s both difficult and misleading to say that we are flying to Israel. We are not going to have a holiday in Israel. We are not going to go clubbing in Tel Aviv. We aren’t going to “Israel” – even if we are able and planning to visit cities and towns that now exist within the borders of Israel. We are visiting Palestine, our Palestine. To do this, we must travel through Israeli ports and be permitted entry by the very state that cleansed and displaced our families from their homes.

The situation for Palestine and Palestinians all around the world is unique. For many, it has been archetypal of so much injustice. However, it sits within a global border and imperialist regime that not only allows the situation to remain as it is but also helped to create it in the first place.

The British Empire and its dissolution created geopolitical strife across the world. Palestine and the creation of the state of Israel in 1948 on top of an already-inhabited land is one example of that. The borders carved out in South Asia only months earlier during Partition led to decades of violent conflict, displacement and death. The announcement by India earlier this month of the revocation of Kashmir’s “special status” that gave the region and its residents some autonomy is the most recent example of this – and for years the situation in Kashmir has been likened to Palestine. Similarly, Chagossians still await the ability to be able to return to their homes in the Chagos Islands – taken by the British in 1967. Britain evicted the entire population of the Islands before inviting the US to build a military base there. Despite a recent International Court of Justice ruling that the continuing British control (and US use) of the Chagos Islands is unlawful, Britain is not backing down – and today even deports Chagossians in the UK to Mauritius.

The global border regime relies on the world wide acceptance of the decisions and practices carried out. Whilst being detained in an immigration detention centre in Israel, I was held alongside others who originated from Arabic-speaking countries, as well as people from the Ivory Coast seeking asylum and from Eastern Europe looking for work. Back in Britain, I know that thousands of people are also held in immigration detention centres indefinitely, sometimes stopped and denied entry for an assortment of reasons such as “acting suspiciously” or because officials at the border believe that they would overstay their visas. The UK government seems committed to violating the rights of others on British soil, so they wouldn’t defend mine in another country.

This is why the Palestinian struggle is an anti-colonial struggle: an ongoing pursuit of the liberation of Palestine from a settler-colony and the right to self-determination for Palestinians. I also believe that our struggle is one of resistance against violent borders, and for freedom of movement. These are not two separate struggles but are intrinsically linked, best expressed through the Mexican slogan: “We didn’t cross the border, the border crossed us.”