In October 2017, archaeologists gathered around a patch of grass in Moss Side, Manchester, not knowing what treasures they’d discover. Their hope wasn’t to find prehistoric secrets, but to unearth the epicentre of nightlife for people of colour (PoC) from 40 years prior.

People often zoom past the mundane mound which lies a stone’s throw away from the area’s beer brewery in their cars everyday, unwittingly overlooking a place where the likes of Bob Marley, Muhammed Ali, and Chaka Khan once kicked back and smoked “the good herb”. While unearthing The Reno, it has been described simultaneously as a “den of iniquity” and a haven for Mancunians of colour. Among the artefact haul was a bag of red Lebanese hash from the 70s, a pair of green flares, rubber from the momentous turntable, as well as a nostalgic record bag from the Spin Inn, a historic record shop that stood above the club, where the club’s influential DJ Persian used to source all of his American imports. Unlike most digs, the people holding the shovels were intimately connected with the space.

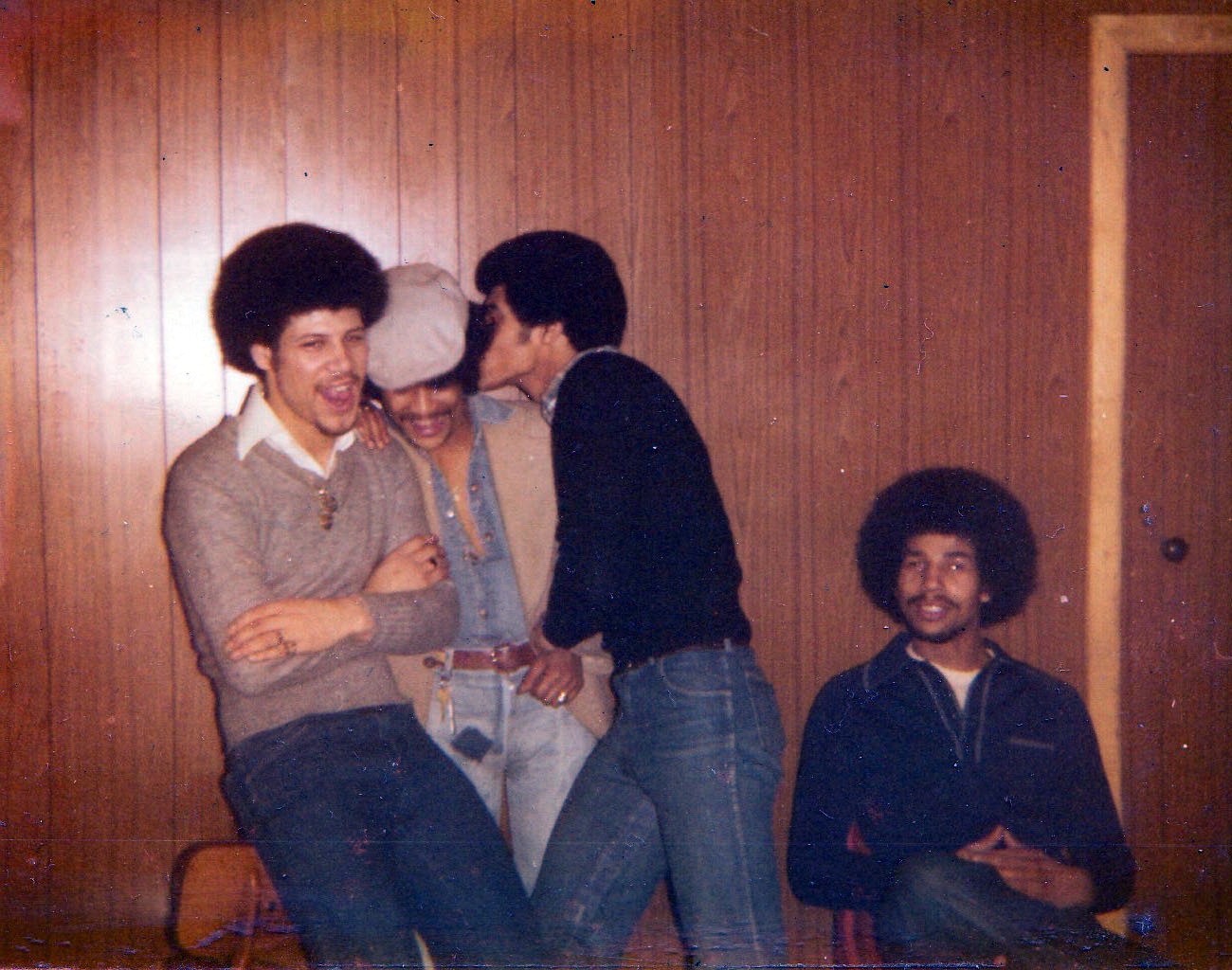

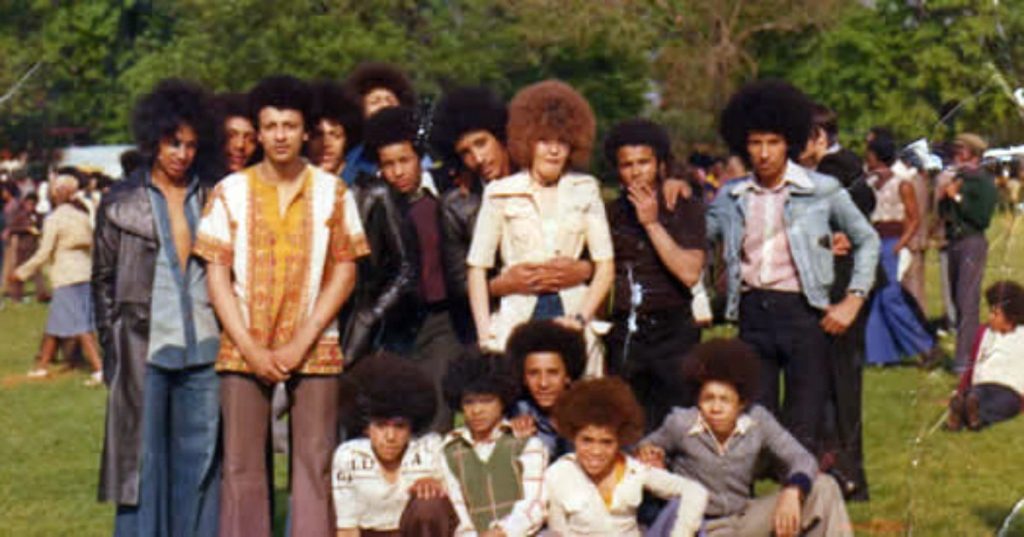

Last year, playwright Linda Brogan decided to excavate the club, which opened its doors to customers from 1962 to around 1986, to reconnect with her old stomping ground. “Half-caste is a word that nobody likes, but I was just half-caste and it was nothing big to me,” Linda explains in her gravelly Manc accent. The word has fallen out of fashion and favour, but even though they admit its political incorrectness, the label allowed them to forge a community. She recalls how her and her best friend Suzie – who is also mixed race – first entered The Reno together hand-in-hand. “It was a bit like the Italian in the film Goodfellas, if you were like us you were ‘made’ in the Reno. It’s how a lot of us were conceived [in the time] of ‘No Blacks. No Irish. No Dogs’,” she says.

“They were rejected by white clubs and black clubs and were left in the middle. The Reno became their place where they could forget about their problems and kill the night”

The speakeasy was a mix of grit and glamour; as Linda’s friend Mark Smith explains, the dancefloor was like a scene from One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. “To me the Reno stunk, it was a structural deathtrap. The toilet was like a bathtub full of piss,” he says. “I felt sorry at times, for strangers who were being stalked unaware they were going to get robbed. Apart from money it was a form of protecting the Reno from strangers who thought they could come down and take the piss.” Despite all this, Mark says its where he earned his “street PHD” and had the best nights out of his life.

Linda’s passion for The Reno stems from difficult encounters with people who deny her the right to be both black and white. The Reno, in her words, was “wall to wall half-caste,” and it was the one place they felt they didn’t have to compromise either side of their identity. “Suddenly, since I’ve kind of been in the arts, I’m black. The one place I could be mixed race, biracial, dual heritage, or whatever you want to say, was The Reno. So going back there was kind of claiming back my own identity.” She continues: “It’s crazy! My mum is white, and you’re brought up mostly by your mum, aren’t you? I don’t know how to do chicken, rice and peas but I can do a mean cabbage and ribs because my mum is Irish.” A fervent frown creases her face as she shakes her head. “Why should I get rid of part of me? That’s insane!”

The dig took 19 days and was assisted by ex-punters and professionals who partied next to its remains at the end of the dig. Having spent a couple of weeks trying to understand the lasting allure of The Reno, and why it meant so much to people, I was met with joyful screams, laughter, and tears as they recalled their heyday. The club was famously “addictive”. “I went down once and didn’t leave for 16 years. If you wanna be a superstar, inside The Reno is where you’d be a superstar,” Linda explains. “But you’re not a politician or whatever, you’re a criminal and you’re the best criminal you can be. So, women are open prostitutes and they’re beautiful, we’re not like: ‘Oh she’s a sad bitch’. We’re like: ’Oh my god that person’s like a ‘super one’, and her clients are ‘super ones’.” The dig was about “not being ashamed”.

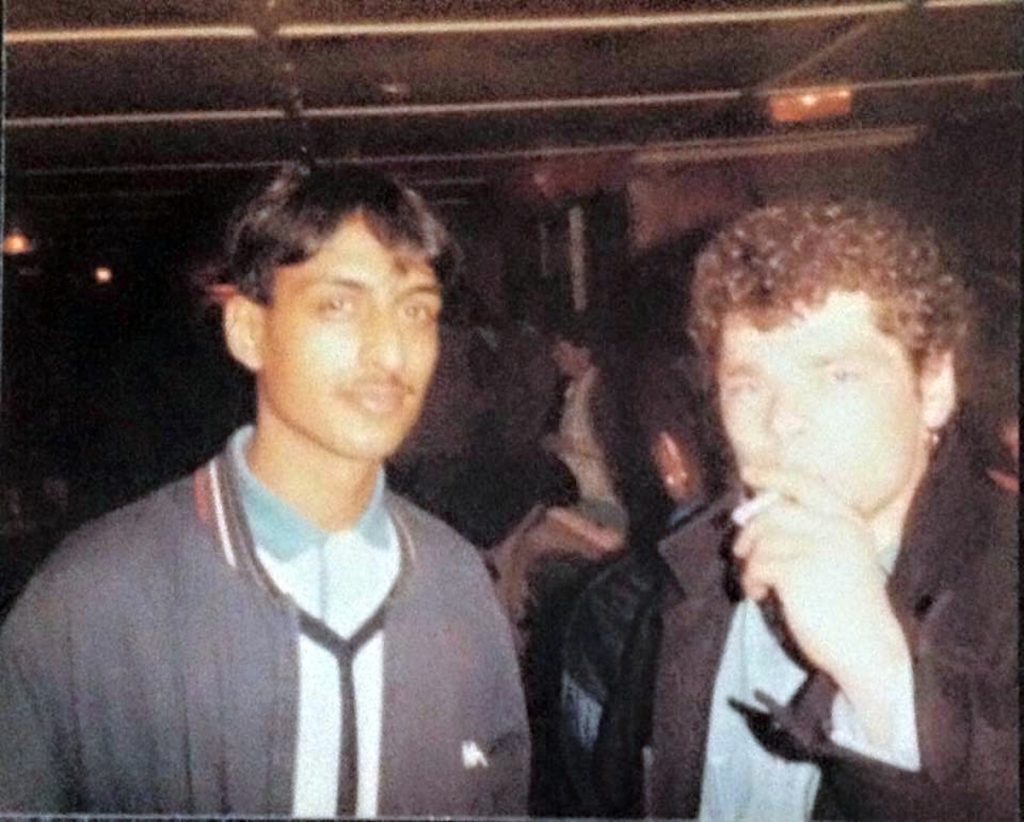

To those who went, it was just music, marijuana, and “magic”. You just had to be a bit of a “character”, or be a bit of a “psycho”, as one of the white-skinned regulars known as Triggy tells me. The clubs and bars in town were awash with blatant institutional racism, and boys with “fros” were regularly turned away because their hair was a “fire hazard”, or without any reason at all. In this world, a mere 20 years after the end of the Second World War, racism was outrageously in your face by today’s standards. And, PoC learned to expect it. Rather than trying their luck in the white clubs, places like The Reno erupted in Manchester’s black neighbourhoods like Moss Side and Hulme, where people could listen to the tight-lipped DJ spin American funk and soul imports that you couldn’t hear anywhere else in the earlier days of the Northern Soul club movement. And it had scant regard for the fire hazards uptown used as an excuse, Suzie recalls. One of the first things she noticed was the smell of weed. Once you opened the door “it was just like a haze that hung nicely in the air, it was always a secondary high for anybody who didn’t smoke”.

DJ Persian, who played The Reno seven nights a week for a time, had a vision of creating a “speakeasy atmosphere”. We meet at the Radio Diamond studio in Moss Side where he now plays a three shows a week. Back in the day, his vision was to entice people with nothing but the music, his eyes light up every time he speaks about his Reno track list. Persian famously didn’t speak to anyone, with some people thinking he couldn’t. “People didn’t come to listen to my chatter. They came for the music and the music is what I delivered – I expressed myself in the music,” he explains in his softly spoken Jamaican accent. He agrees on its importance to dual heritage punters, reminiscing on the unique hardships faced by mixed race Mancs of the time who were shunned by both worlds. “A lot of mixed race youngsters, from mainly African backgrounds, didn’t have a nice existence growing up. They ended up in care,” he says. When they became teenagers they entered the world of nightlife to find the colour lines drawn at club doors too. “They were rejected by white clubs and black clubs and were left in the middle. The Reno became their place where they could forget about their problems and kill the night.”

There were, however, regulars of varying ethnicities. Linda tells tales of a “super cool” Sikh man who used to play the bongos. There were other “characters” like the mixed-race Frank Pereira, often referred to as the club’s “king” due to his captivating moves on the dance floor. 56-year-old Barbara Bell speaks excitedly as she recounts with 85-year-old fellow Reno veteran Coca Clarke as we sit in Coca’s well kept living room. A teenage Barbara flicked through the Spin Inn’s record collection when “Kevin who worked there said ‘If you want to hear that kind of music, you’ve got to get down The Reno’, so all us little kids, I looked about 10 back then, we were trying to get into The Reno to hear these tunes”.

‘Guilty’ by Barbara Streisand, ‘Goodbye My Love’ by The Drifters, and MJ’s ‘We’ve Got A Good Thing Going’ were all spoken about as DJ Persian’s classic end-of-night tracks, but the list of Reno tunes is never-ending, with everyone favouring their individual classics. This was at a time when, for poor people, the only source of music was the radio. Nowadays, you can find anything online, but The Reno turntables were the Spotify playlist of its day.

Until the birth of BBC Radio 1 in 1967, the radio wouldn’t play the American imports or black music young people wanted to hear, which resulted in people relying on offshore stations like Radio Caroline or Radio Luxembourg to hear them. Pleasure seekers relied on DJ Persian, DJ Dennis, or Hewan Clarke (who also spun tracks at The Hacienda) and their record collections to hear the newest music. Triggy cheekily tells me of the tricks he used to play to try and distract them with a nicely rolled spliff while he jotted down the name of the record by peeking at the record sleeve that was playing down with his bookie pen. Having rare records set you apart from other DJs back then.

“Mr Manchester”, Tony Wilson of Factory Records, had his stag do at The Reno. While Mohammed Ali came down to relax, Chaka Khan was “on the front buying a draw”. Barbara knowingly remembers and explains those in-the-know called The Reno “the front”. Numerous musicians and actors touring would end up at The Reno when they were looking for good weed and good vibes after show. The Coronation Street crew would find themselves in the funk and soul basement, as well as the king of reggae, Bob Marley.

There was a real sense of escapism in The Reno, that people could put on a persona and be the superstar that they always dreamed of being, regardless of what happened outside those doors. And, they could do it until 6am if the owners had “come to an agreement with the police”, as Suzie puts it. It was one of the only places in the city open so late.The club’s king and queen, Frank and Chips, earned their unofficial titles because of their infectious attitudes, sass, dance moves and slick get-up. “No matter what the weather, Chips would wear a gobsmacking floor length white fur coat”, Linda remembers. At the mention of Frank, Triggy breaks down into immediate tears following Frank’s death last year, reaching for a tissue. “Oh Frank Pereira, now he was the man, he was really the man” he says over and over until he composes himself.

The eldest of the routine Reno goers, Coca Clarke, excitedly recounted the moment she got a phone call from Bob Marley, asking to speak to her late daughter Maxine Hooker whom he met down at The Reno. “Bob Marley didn’t have bodyguards, he just had his posse. In the summer of ‘76 he took my daughter out. It was a Sunday morning, the phone goes, and he said ‘scuse me ma’am’. He talked like an American. ‘Is Maxine there?’ I said, ‘No, she’s just gone to the shop.’ He said, ‘Well can you tell her Bob called’”, she recounts imitating his accent. “I said, ‘Bob who?’ Which is when he said ‘Bob Marley,’ I said, ‘THE Bob Marley?!’ He said, ‘Yes ma’am,’” Coco relays. He promised to call back in 15 minutes and then arranged to take her out. “She said he was a nice person but he wanted her to chase him, and my girls were very strong like me and don’t run after men,” she adds.

“It was a bit like the Italian in the film Goodfellas, if you were like us you were made in the Reno. It’s how a lot of us were conceived [in the time] of ‘No Blacks. No Irish. No Dogs’”

Despite the magic and community, The Reno was a scene most parents didn’t want their children going to, and it was branded “seedy” by many. It was an unapologetic place that said yes to anyone from any background, so it entertained people who wanted “easy money” as Triggy puts it – criminals in the eyes of the law. Drug dealers, students, lawyers, artists, musicians, and actors, too. There was a Monday to Thursday crowd made up of locals who would likely pick your pocket if you weren’t a friend of a friend, while Persian explains the weekend brought people from as far as New York who specifically travelled to experience the front.

In the late 80s, the club found itself at the centre of gang violence and drug addictions, and the council knocked the whole building down. In the decades that followed, it faded into obscurity. The Hacienda has a lasting legacy in nationwide club culture and has been canonised despite being a hotbed for hard drugs. The city’s underbelly of drug dealing gangs and criminal firms were like magpies to a jewel, violently trying to gain control of the territory. Yet the reputation of The Reno as seedy meant its history had been largely buried until now. It’s fortunate then that someone like Linda is working to correct the history books by reminding us of the significance of Moss Side’s clubs on the city’s nightlife.

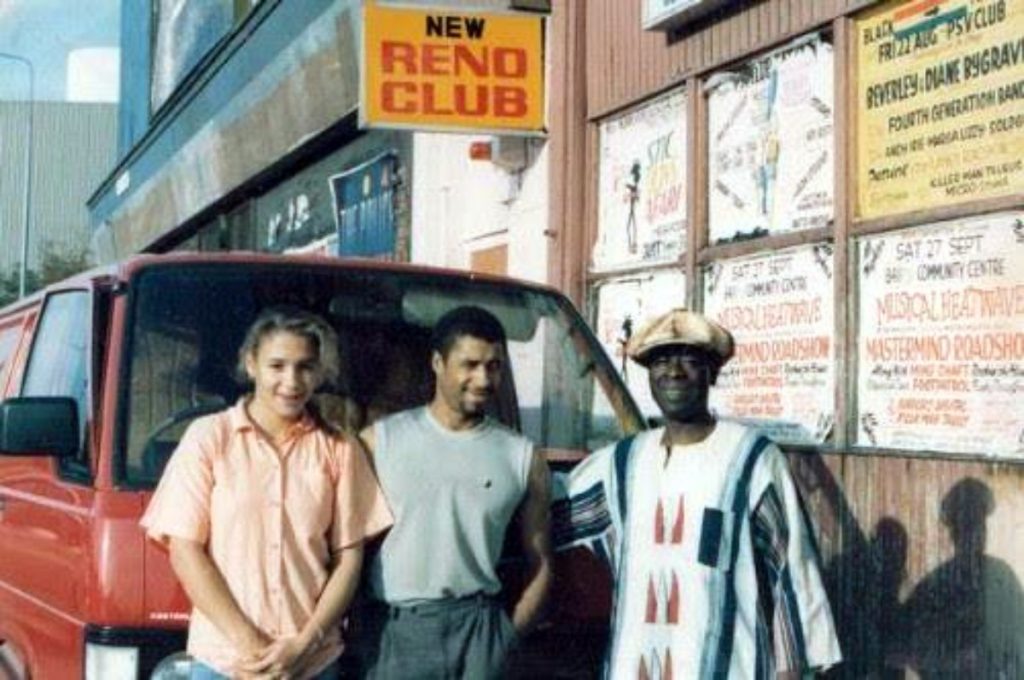

A former Reno regular (right) and Linda (left) take a break during the dig

Soon the artefacts from the dig along with memoirs will be on display at Whitworth Art Gallery for public display and on 23 November the old regulars got a sneak peek. “We colonised the gallery. Our teen photos projected huge walked up the stairs. Our memoirs, huge, obliterated their art. We danced to Reno DJs in their main hall. As our excavation footage covered our their exterior walls.” After finding herself internally accepting racism by constantly having to centre or appease white narratives in her career as a playwright, Linda says The Reno gave her a chance to tell her own story using the “real voices” of the veterans. “I often feel like screaming and crying about the fact that we have to package our experiences in a way so as not to make white people feel racist. This journey is to undo that,” she shouts. “I love them swearing and I love that they’re criminals, I love that it is our real story.”

It’s inherently a good thing that clubs aren’t born out of forced segregation and that society has progressed an incredible amount in the last 40 years. As the club’s regulars returned to the site for the excavation last year, Linda says it “resurrected the community” as they “hugged like it was decades and talked like it was yesterday”. Long live the memory of The Reno and let its die hard fans be testament to how clubs can unite entire communities when they’re allowed to thrive. “There’s nowhere like it and there never will be again”, Triggy says, throwing his arms in the air.

The Reno exhibit will be on display at The Whitworth Gallery until March 2020, find out more here.

From gal-dem’s third print issue on the topic of home.