Salooni was born from four Ugandan girlfriends sitting on the floor talking about hair. Although we all grew up in various countries, Zambia, Kenya, Uganda and the UK; each of us cooed in agreement as we learned that when it came to hair, many of our experiences are shared. Aida Mbowa, writer and theatre director with a clean-shaven head, made us laugh by asking us to consider the plight of the lone braid on the floor of a predominantly white high school, and the black girl who walks past it, eyes averted. Gloria Wavamunno, designer and director of Kampala Fashion Week, her elegant grey cornrows elevated by an undercut, talked about understanding the power we give hair when a vindictive family member cut off her long, soft curls as a child. Darlyne Komukama, our photographer, spoke of being called Rasta in Malawi and Zanzibar, and the different reactions she receives to her long dreadlocks. I (Kampire Bahana, writer, arts organiser) returned to the memory of my mother telling my sister and I to oil each others’ hair “You’ll be grateful for each other when you’re older” she said. Many decades later, we are.

Salooni by Darlyne Komukama

Out of that conversation came Salooni, an art installation that has visited four cities in three African countries. It is our contribution to a conversation black women have been having, now more frequently online with the natural-hair-movement, but also one that our mothers, grandmothers and great-grandmothers had with one another and continue to have with us. The styles, strategies and practices of hair care passed down across time and migrations.Today, this gives black girls not only a history of our hair, but a science of survival in a white supremacist world, as well as a glimpse of our potential futures.

Salooni by Darlyne Komukama

We try to reflect all of these timelines in our ongoing photo project in a number of ways.For example, we conjure up a space which pays homage to an 18th century Madagascan princess, and we salute contemporary Congolese fashion with one hairstyle (Oeufs-oeufs, they call it). Black hair has survived the interruptions of slavery and colonialism. In the twists and plaits of our styles we can find messages and lessons from our ancestry projected into the present and sent into the future for our children to untangle.

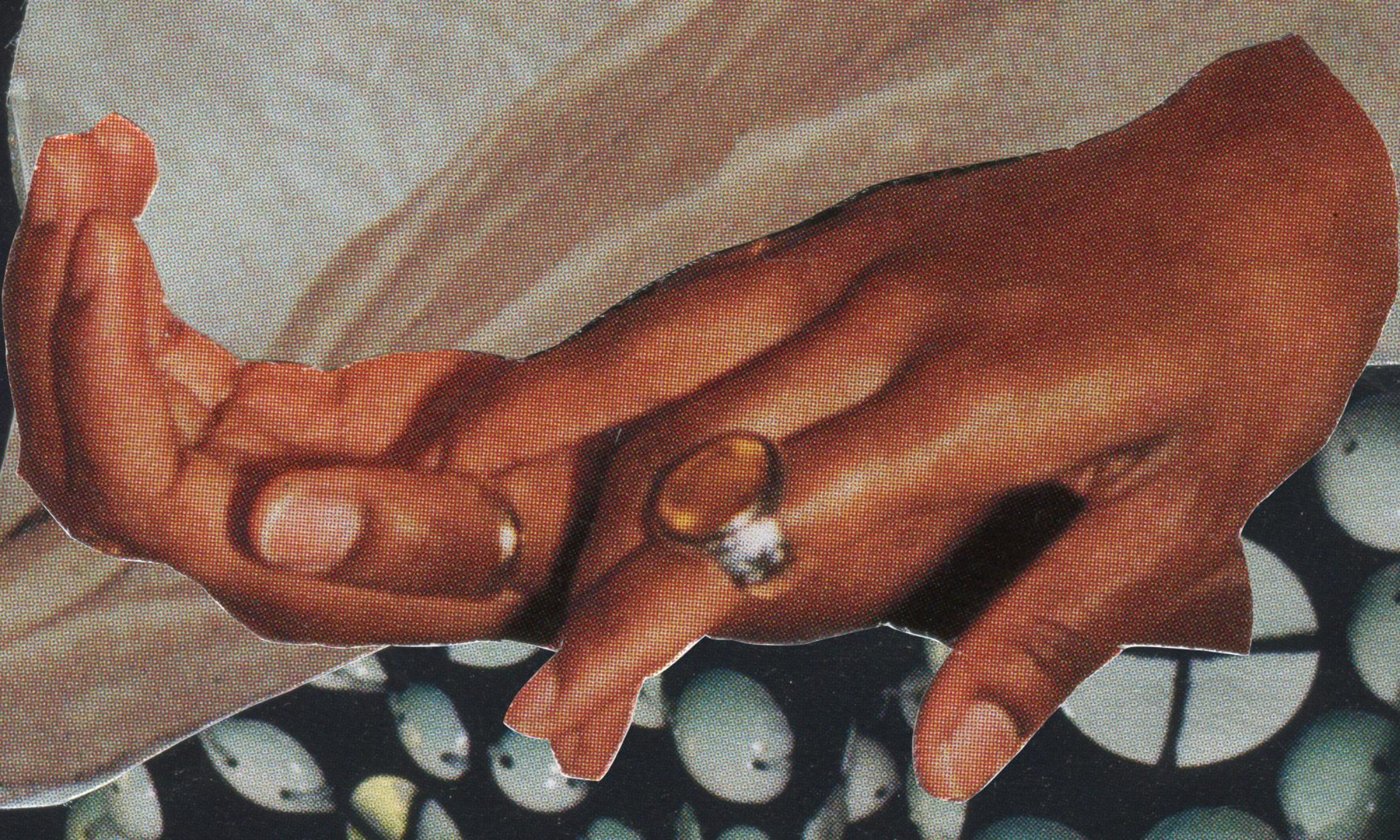

Much of our collective hair history has been painful. In confrontation with western hegemony our hair has been labeled repulsive and a symbol of our inherent moral failings. So we have pressed, straightened and hid it; scalding ourselves in the process, wounds blistering over like chemical burns, coils falling out in scary clumps. Our history is aunties who will not stop telling our toddlers their hair is good, bad, kinky, sisal or kaweke. It is walking into the salon, relaxed or natural, only to be berated and walking out having paid exorbitantly for a coif you now only hate. It is needing to wear weaves for interviews and jobs at white firms, whilst being told by black men how you must not love yourself enough.

Salooni is first a space, in which black women can have these tough conversations. It aims to help find and create communities of care. In it we dream of a future where black hair is free to be its purest expression. A future where our hair is no longer a site of trauma and the history and politics represented therein. Instead, Salooni aims to give back the respect our hair deserves. At La Ba Street Art festival we recreated a typical Kampala salon, and gave out free styles and head massages. On the walls of the Salooni we projected film and pictures past and present of majestic black women, they rang out with the confessions and knowing laughter of girls chatting hair. And the girls had a lot to say; of the intimacy of sitting in the heat of another woman’s thighs as she caresses your head, of the man in every black salon across the globe, who stops in to try to sell you DVDs and plastic trinkets, of the mixture of optimism and despondence that led them to the “big chop”.

Salooni is also the joy and beauty black people find in adornment, that we have always taken from our crowns. At Chale Wote Street Art festival the Jamestown community that hosts the festival really came out for Salooni, helping us setup and break down the installation, and giving each other love and great looks in our chairs. So many little girls with not an inch of hair on their head, sat down to get their heads spritzed with aloe, rubbed with shea butter, and maybe sprayed with glitter. We felt deeply privileged to have been a space for our hosts to be adorned among the artists and fashionistas, the incredible visual feast that Chale Wote is every year.

Salooni is a container for these conversations. We honestly did not expect the response that we have gotten so far. The photo project, which seemed a little abstract when we were attempting it, has been embraced wholeheartedly online by those who see the continuity of black hair styling documents where written history has failed. The installation audience has come to our Saloonis’ not just for the free hair styles, but prepared to discuss the difficult questions around hair, and willing to share intimate gestures with strangers.

While the natural-hair-movement online has been a godsend for black girls all over the world, it is one that has so far been the diaspora talking and the continent taking notes. In Salooni we also make ourselves heard. In 2017 Salooni will be in London and Kigali, a vessel for the aspirations and memories of Rwandan and black British women detangling their shared and varying experiences.

Salooni was created by Darlyne Komukama, Kampire Bahana, Gloria Wavamunno and Aida Mbowa. Find our more on their Tumblr and Instagram.