Hanging out the door of a train chugging through Kerala, a blur of vivid green rushes past me. Paddyfields and small farming villages, fishermen chucking their lines out onto vast expanses of the Pamba river, plumes of smoke emerging above industrial towns. The brilliant green zips past, everything, everywhere. It was exhilarating. There are few other moments in my life I can remember feeling so fiercely alive. Hanging out the door of a day-train from Thiruvalla to Kozhikode, I grasped on for dear life, watching faces come into view just as quickly as they vanished.

The Indian Railway System is iconic, one of the oldest railways in Asia, and one with the most scenic views. The rickety locomotives, still stuck in their colonial-era heyday chug along with people spilling out the doors, windows and rooftops. A true “authentic” experience. In a world where travelling beyond comfort zones is becoming more common, Instagram feeds are flooded with matchbox shops, gritty roads, kooky forms of transport and “authentic” markets. The view hanging out the side of an Indian train would have been perfect for this particular niche.

These exciting adventures taken now and again for me, are also well-known death traps across the subcontinent. In 2016, 657 people died falling off of trains, whether it be a slip of the wrist, overcrowding or simply being shoved out unceremoniously by the almost-too-heavy-to-open door. The Indian Railway is also the world’s largest toilet. With an overwhelming 3980 tonnes of faecal matter ejected onto the tracks every single day – that’s almost eight tonnes per track per day – from the squat toilets on board. Bet that doesn’t make it to the Instagram caption.

“To be able to say they have seen ‘the real world’ is to have a badge that can be worn with great pride…”

Having been born in Kerala and brought up in the UK, I’ve been privileged enough to be both the insider and outside when in India. I have been guilty myself of yearning to experience the “real” India on each return – wanting to hang out of train doors – only to realise that what I wanted was something far from what I know well. Something “authentic” or “real’ so I could hold my head up high and say I know what true India is like. But I was kidding myself. Authenticity was code for poor infrastructure, poor sanitation, little safety and minimal access to communication.

As people go abroad to find themselves in South East Asia or South America, I hear them talking about their search for an authentic experience. To be able to say they have seen “the real world” is to have a badge that can be worn with great pride, whether that be in the form of elephant harem pants or an Om tattoo. Often those who go in search of this real world with “real” experiences are just those in search of the less Westernised, poorer, deprived areas.

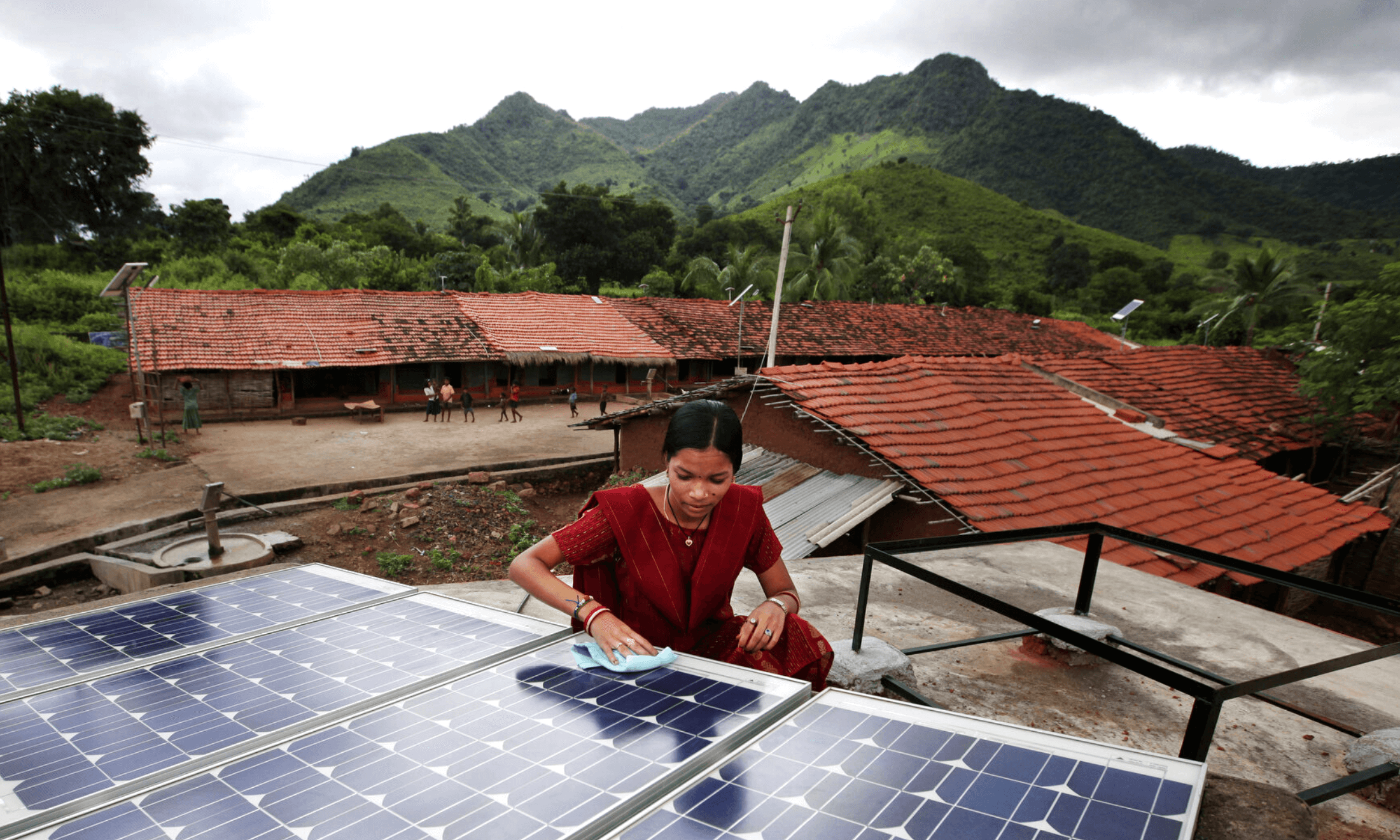

This can leave some countries of the global south in a bizarre limbo as they develop better infrastructure, sanitation measures and access to communication and safety – none of which the soul-searching tourists want to see more of. Take Lebanon, a country filled with many clichés, it is home to the glitzy, glamorous Beirut with its high-rises and French-chain stores, as well as being a gem for its culinary delights. But there is also a sprinkling of buildings covered in bullet holes alongside bombed out and deserted hotels, stark reminders of the civil war. Lebanon is both glamour and strife, rich and poor, easy and hard.

“To hear people describe how ‘whimsical’ it is to plan life around the daily power cuts is the peak of privilege”

To hear people describe how “whimsical” it is to plan life around the daily power cuts is the peak of privilege. Having a fortified obstacle course for a pavement on your way to work is not amusing. Nor is having to buy water regularly because the government-supplied water is undrinkable. This experience of slowness and chaos is something which many people cite when they vouch for the authenticity of a place. They aren’t happy with the high-rise buildings, shiny transport or well-presented seaside walkways. Unless they see the grittier side of life, they feel they’ve been fed a lie. By the same logic tourists visiting the UK haven’t seen the real Great Britain until they’ve been to the most deprived areas.

To go in search of this imagined “authentic” is to pretend as though the areas prospering and modernising don’t exist, that they aren’t a part of what constitutes the real world. Authenticity is allowing countries of the global south to be as nuanced and complex as those in the global north. Authenticity is accepting that modernisation does not make a place any less real – that cultures are in a continuous state of flux, constantly evolving, adapting and acculturating. Authenticity is what emerges from the ongoing tension between demands for a better quality of life and the preservation of a local evolving culture.