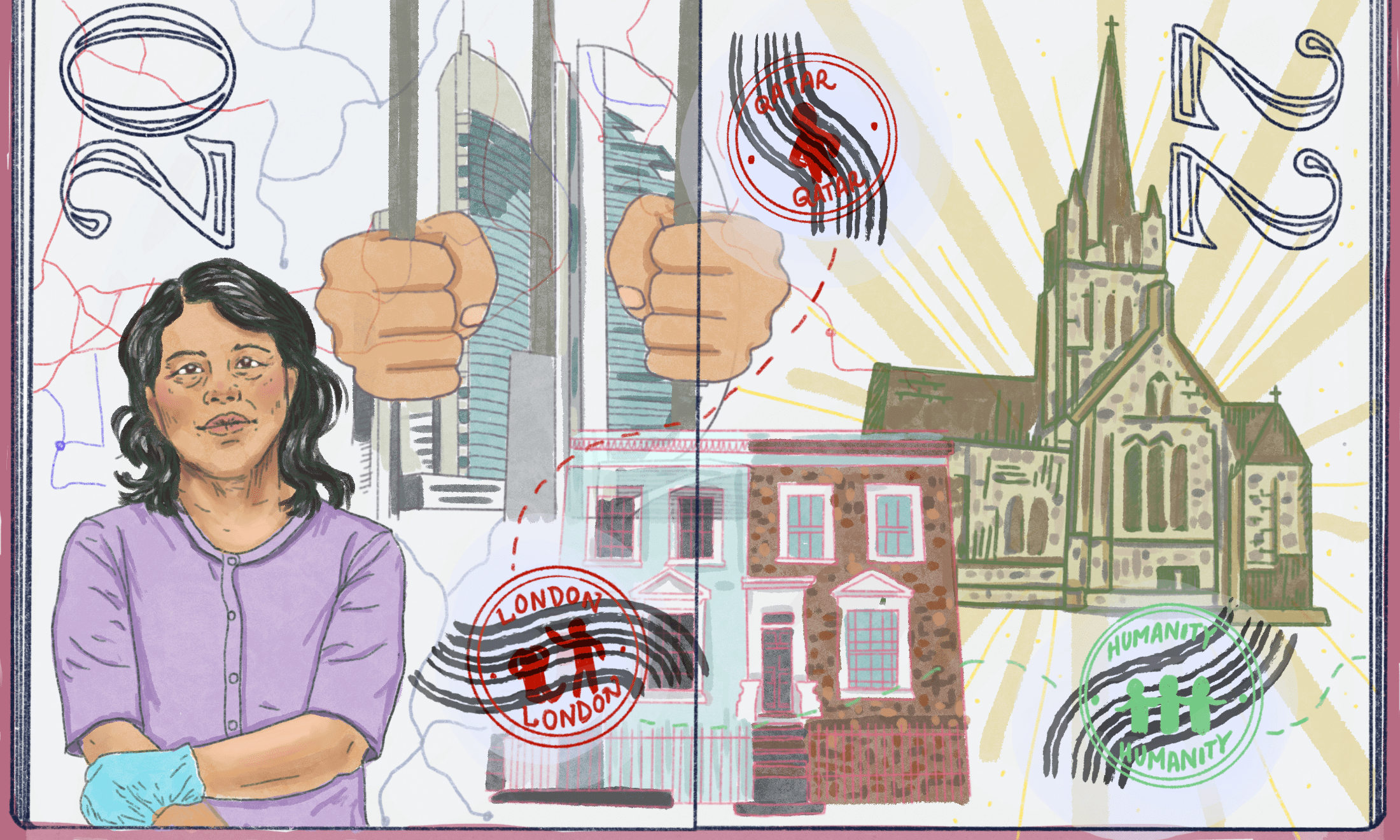

Illustration by Serina Kitazono

Data protection is a hot topic: after the Cambridge Analytica data scandal, an estimated one in 20 Facebook users in Britain deleted their accounts. In the context of the “hostile environment” in the UK, where data is shared between the Home Office and other public bodies, including police forces and schools for immigration enforcement purposes, new data policies and legislation sound like a step in the right direction. However, according to Lara ten Caten, a lawyer at human rights group Liberty, far from implementing benign laws, the government is building a massive secretive migrant database: “an ID system in all but name”.

A 2018 Home Office inspection report explains that the “Status Checking Project”, part of a plan for “deepening the compliant environment”, will provide immigration status checks in real-time. The database is being developed alongside the worrying introduction of an exemption to the General Data Protection Regulation 2018 (GDPR), which permits a loophole in data protection rules for the purposes of “effective immigration control“. This means that people who want to know about any data held on them by the Home Office could be blocked from accessing it. This chilling new law was challenged last month in UK courts through a judicial review brought by Open Rights Group (ORG), a digital campaigning organisation, and the3million, a campaign group for EU citizens in the UK.

“The government has created a discriminatory, two tier data protection regime”

Rosa Curling, a solicitor at Leigh Day, the firm bringing the judicial review on behalf of the two organisations, explained that the government has created a “discriminatory, two tier data protection regime”. Their judicial review argued that the definition of “effective immigration enforcement” was too vague and that denying people’s access to their own data would make appealing decisions and submitting new immigration applications more difficult.

Lara shared her concerns that the blocking of data access “strips people of the very rights the [Data Protection] Act is meant to protect”. Lara finds this particularly alarming because the Home Office, as evidenced by the destruction of vital documents during the Windrush Scandal, is “notoriously bad with data” and could be making “life-changing decisions” on people’s residency rights on the basis of incorrect records. A number of civil rights groups and migrants’ rights campaigning and advocacy organisations, including the Joint Council for Welfare of Immigrants (JCWI) and Race Equality Foundation, joined Liberty and Leigh Day in condemning the loophole, which is set to disproportionately impact communities of colour. Satbir Singh, Chief Executive at the JCWI remarked, “Why should migrants be denied the right to have their information processed lawfully, fairly and transparently?”

“Since the start of the year, 60% of data access requests have been rejected due to the new loophole”

The practical implications of the new database and data protection loophole are cause for grave concern. A report published by the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration earlier this year stated that the Home Office is conducting “poor and inconsistent record-keeping”. If individuals are blocked from accessing incorrect data held about them, they will be less able to effectively bring new applications or appeals against ill-informed Home Office decisions. These implications aren’t hypothetical: it has been reported that since the start of the year, 60% of data access requests have been rejected due to the new loophole. The majority of Home Office decisions to reject migrants and asylum seekers applications to live in the UK are actually overturned when they are appealed, meaning that applicants are arbitrarily having their lives interrupted and thrown into chaos. If people cannot access their data in these cases, unfair rejections cannot be challenged.

Taken in the context of the government’s efforts to intensify the “hostile environment” for migrants, the new measures seem like sinister and opportunistic moves to entrench anti-migrant laws that former Prime Minister Theresa May brought in during her stint as Home Secretary. The Immigration Act 2016 ushered in new policies and processes such as fees for accessing healthcare, which have the impact of preventing migrant communities from accessing vital public services. The Windrush scandal, which was brought to the public’s attention in 2018, shed light on how these laws affect peoples’ daily lives, stopping them from renting property or keeping their bank accounts open. The measures have the effect of perpetuating a state of fear and constant insecurity for migrant communities.

“New data laws are being used as a tool to make it difficult for migrants to live and work in the UK”

These new data laws are being used as a tool to make it difficult for migrants to live and work in the UK and secure their status. As Jabeer Butt of the Race Equality Foundation put it, “good data, shared appropriately, is key to effective public services and tackling health inequalities”. The prospect that data is instead secretly being collated and stored for “status checking” feels like a slippery slope towards a Big Brother state. By implementing the immigration exemption in data protection law, Jabeer says that the government has undermined trust in public services by “turning more public sector workers into immigration officers”.

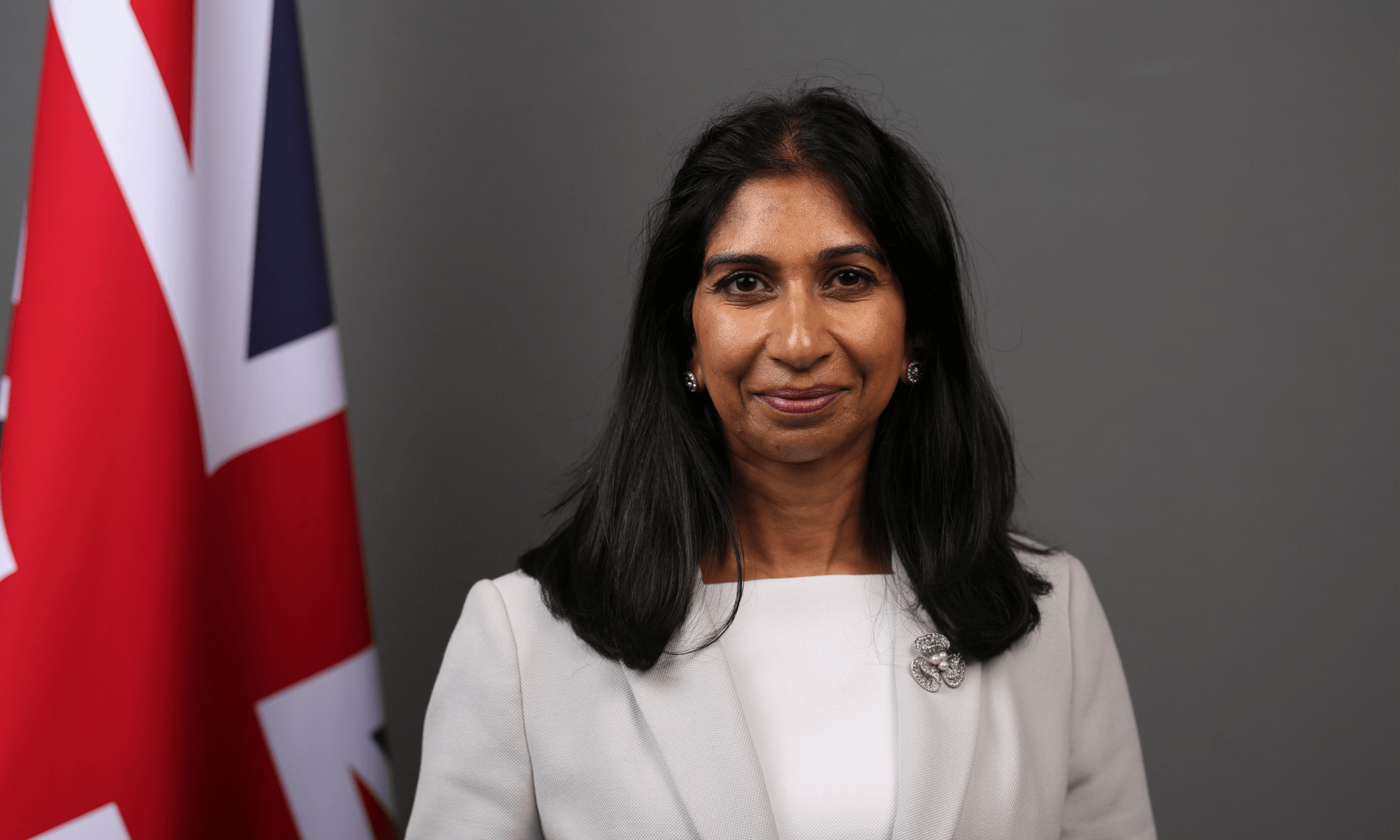

The potential for creep of powers and governmental overreach is especially prescient now with the appointment of Priti Patel in her new role as Home Secretary. Priti, herself a child of migrants to the UK, has an iron-fisted approach to both immigration and law and order: she has voted for the continued detention of pregnant women in immigration prisons and against permitting Syrian children to seek refuge in the UK. Priti has also historically supported the reintroduction of the death penalty. There seems little to suggest that she will approach the regulation of data with the rights and needs of migrant communities in mind.

When the EU and the UK government introduced GDPR, it had clearly recognised an imperative to protect the individual in a rapidly changing technological landscape. However, the government has failed to meet this objective, instead of seeking to exploit marginalised communities, by using data as a tool for immigration enforcement. The new data laws fail to extend the same protections to everyone, and instead should be understood as yet another plank in the sinister and damaging hostile environment for migrant communities.