Porai Picanerai, one of the Ayoreo-Totobiegosode leaders from the village of Chaidí. 2019 / Photography by X. Clarke

Straddling the borders of Paraguay, Bolivia and Argentina, the so-called “Green Hell” is a wild hostile landscape of relentless heat, towering cacti and wind gusts that shower everything in fine white sticky dust. Otherwise known as “the Gran Chaco”, it’s one of the globe’s only dry forests, and an extraordinary ecosystem of sun-bleached objects, unlikely characters and eerie golden sunsets. It also boasts one of the highest rates of deforestation in the world, driven by a seemingly relentless global demand for land for beef and soya production.

Standing on the frontline of this expanding agricultural frontier, the indigenous Ayoreo-Totobiegosode, a small subgroup of the Ayoreo people, has been fighting to protect their territory and uncontacted relatives from a rapacious deforestation which is eating through their ancestral lands. Earlier this year, they invited me to their communities in the flatlands of the Paraguayan Chaco to learn about their struggles and lives.

Porai Picanerai, one of their leaders, told me why international solidarity is so vital. “I want the authorities to be ashamed,” he said. “We’ve been fighting for our land for so long now. This is our land, and the land of our grandparents. Outsiders always cause so many problems for us. We are getting old and tired, we’ve been fighting this for so many years now.”

For decades the Ayoreo-Totobiegosode have been battling relentless waves of dispossession, manipulation and oppression at the hands of fundamentalist missionaries, Mennonite settlers, Brazilian cattle-ranchers, and other outsiders. Their story lays bare the palpable violence of a colonialist and assimilationist project that never ended. A veritable hell. It is also a testament to the staggering endurance of indigenous resistance and spirit.

There are thought to be over 100 “uncontacted indigenous peoples” around the world today, the majority in the Amazon. For most of their history, the Ayoreo-Totobiegosode were “uncontacted” and lived in the forest: they hunted wild pigs and turtles, collected sweet honey, drank water squeezed from plant roots and generally ate food that made them feel good and full and healthy. They had no peaceful interactions with dominant, non-indigenous societies. Although a useful shorthand, the term “uncontacted” is in some ways a misnomer for many of these peoples. As with many other indigenous peoples, the Ayoreo-Totobiegosode’s recent experience has been marked by a constant friction with and resistance to outsiders.

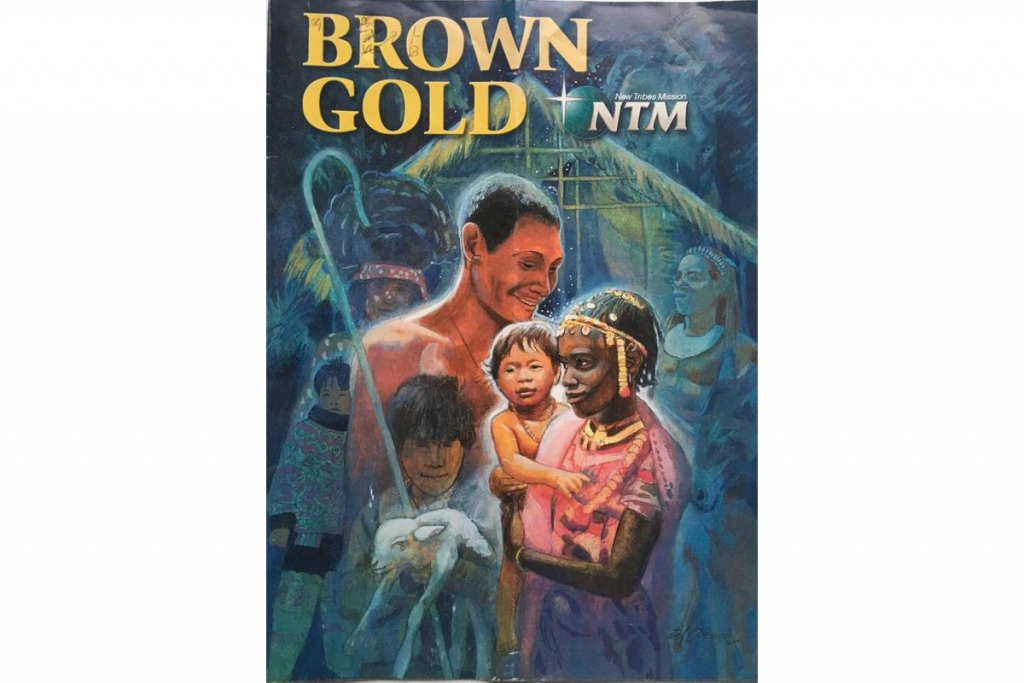

The Ayoreo-Totobiegosode’s remoteness was a precious commodity for the Christian evangelists of the Florida-based New Tribes Mission (now Ethnos360). During the second half of the 20th century, they set up camp in this corner of the “Green Hell”, and with their ideological thirst for “brown souls” invented for the Ayoreo-Totobiegosode a new brand of hell. Determined to reach the most remote or “unreachables tribes” at any cost, they organised cacerías – manhunts – to track them down. Their project, a “conquest for God”, involved violent confrontations in which several Ayoreo died. Those who survived were forcibly sedentarised – brought out of the forest against their will, forced to give up their nomadic way of life. In a process described by many as an ethnocide, they were forced to live and work in mission camps, wear Western clothes, cut their hair and renounce their belief systems.

The New Tribes Mission magazine, Brown Gold, is a historical object which unwittingly betrays the logic behind this (perhaps the first) process of commodification of Totobiegosode lives, bodies and souls. Because the soul of a savage was more precious, more rare and covetable than gold itself.

Chagabi, a Totobiegosode activist and leader who sadly died only a few months after I met him, lived through this as a child. He told me: “The missionaries wanted all the Ayoreo to live in this society, so they could live what the missionaries considered to be a ‘good life’. They believed living in the forest was hard for us, not listening to the word of God and the bible. And they thought that by forcing us out of the forest, we could be saved. This was not what we wanted. After that, many Ayoreo-Totobiegosode died of diseases, respiratory problems, tuberculosis.” I was also told that many Ayoreo died of sadness.

Missionaries seeking to forcibly convert uncontacted indigenous people are still living in the Paraguayan Chaco – and all over the world. Just last year, one such American missionary – John Allen Chau – was killed by the uncontacted Sentinelese people he was seeking out.

Forced contact and religious conversion was only one in a long line of attempts at domination they have lived through. The next one, maybe a more familiar one, made the Ayoreo-Totobiegosode collateral damage in a project to privatise their commons, steal their resources, their land and forests in order to plug them into a global system of production for which they would serve as cheap labour.

The bulldozers moved in. The government answered land demands from agro-industry, handing over land titles to beef companies and in practice encouraging them to occupy and deforest the Ayoreo-Totobiegosode’s territory. They ignored the presence of those who lived in the forest uncontacted, routinely destroying their homes, forcing them to live on the run, fighting off “the beasts with metal skins”.

The stories of a group of Ayoreo-Totobiegosode who were forced to leave the forest by this invasion in 2004 give us a window into the everyday violence of contact. The threat it posed was overwhelming. As written in Lucas Bessire’s book, Behold the Black Caiman: “For [Ayoreo] Totobiegosode, bulldozers became both vehicle and sign for the end of time. They called them eapajocacade, a word that likens them to “attackers of the world”.

The Totobiegosode who have so far survived forced contact and the beasts with metal skins now live in two small communities, and have secured land titles for both – significant, though small, victories. Many continue to die from the health consequences of forced contact. They spend much of the day avoiding the heat in the dappled shade of canopies of thinning fabrics, old towels haphazardly tied in the spaces between trees. Faded, torn; everything ends up the colour of pale amber here. We share endless sips of terere, a bitter and highly addictive tea as they tell me the fight isn’t over.

They are still fighting for the right to self-determination, fighting to protect their lands and their relatives who live in the forest. The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, the continent’s human rights body, has asked the Paraguayan government to protect the uncontacted Ayoreo-Totobiegosode and permanently protect their land, something it has consistently failed to do.

So the Ayoreo-Totobiegosode have set up their own land protection post, taking turns to intercept the invaders who come to chop down their forest and their palo santos. The lands they protect are a green island of forest in a sea of deforestation – a pocket of hope in a pale green grid of barren ranches stretching as far as the eye can see.

Ripped against their will from their life “in the forest”, routinely excluded from the market economy and marginalised from mainstream Paraguayan society, the Ayoreo-Totobiegosode seem stuck between worlds. There is a disheartening continuity and overlaying of the various colonial projects that have shaped their communities and restrict their possibilities for the future.

But at the same time, I see an unbelievable resilience and desire to carve out spaces for hope. Erui, an Ayoreo-Totobiegosode leader tells me how far they’ve come and what he wants for his people: “I want the young people to continue the struggle we started. I don’t want this struggle to be abandoned.”

Survival International has been working alongside the Ayoreo-Totobiegosode for decades. It is the only organisation working globally to defend the right of uncontacted indigenous peoples to determine their own futures and be protected from forced contact