Illustration by Parys Gardner

In 2016, age 22, I decided to go travelling around South America. Like most long-haul trips, there were a couple of vaccinations recommended for me before I took to the skies. They included yellow fever, hepatitis and tetanus. Even with a slight fear of needles, I took a long-overdue trip to my local GP. Before giving me any jabs, she asked what vaccinations I’d had previously and to be honest, I didn’t know the answer. So after inspecting my records, my GP was pretty shocked that I hadn’t got some key jabs at all.

Vaccinations (and the lack thereof) have been a much-debated topic in recent years. An outbreak of measles in London has affected more than 300 people in the past six months (there has been a separate outbreak in the US) and new studies are indicating that the HPV vaccination, started 10 years ago, has dramatically decreased cervical disease. So, whilst I lay back on my GPs bench aged 25, I couldn’t help thinking about the fact that I hadn’t got my HPV vaccination all those years ago. According to the NHS, children in the UK should be having at least 10 to 11 vaccinations. I, for

The more I thought about it the more I realised I have a lot of black friends and family who don’t go to the GP or hospitals for every sneeze or tickly throat, opting for a lemon and ginger tea or natural remedies over a string of antibiotics. I also know lots of people who haven’t been vaccinated as children or choose not to vaccinate their children now, but I wasn’t sure why.

Choosing not to vaccinate children isn’t specific to black people, but there is evidence that black people in the UK and America are less likely to get vaccinations. A study from 2015 found that vaccination coverage was significantly lower among black people, Hispanics, and Asian people compared with non-Hispanic white people. In the UK, a study at Napier University was conducted in 2016 after international research indicated lower HPV vaccination uptake rates among black, Asian and minority ethnic communities. It concluded that vaccination rates will only rise if there is a greater partnership between health services and BAME youth, parents and community leaders.

“I realised I have a lot of black friends and family who don’t go to the GP or hospitals for every sneeze or tickly throat, opting for a lemon and ginger tea or natural remedies”

There appears to be a marked difference between black people who choose not to vaccinate and white “anti-vaxxers”. Dr Carol Lynn Curchoe, an American reproductive biologist, argues that vaccine denial is “one of the worst types of white privilege” because middle class white women are generally more affluent and therefore enjoy more access to healthcare than black women. They can choose not to have a vaccine and know with some certainty that they will be able to deal with the consequences of an illness.

What I have discovered is that there are a plethora of reasons why many black people choose not to vaccinate. Some are wary because they don’t know enough about them; because of the side effects caused by the vaccinations or because of personal negative experiences.

The MMR scare of the 1990s and noughties hasn’t

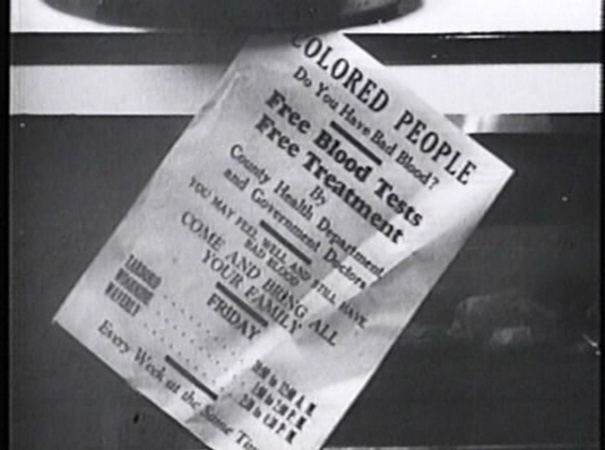

Lots of people in the black community have some level of distrust when it comes to the medical profession and rightly so. The mistreatment of black people in medical science is nothing new. What happened in the Tuskegee syphilis trials in America is a perfect example of how black bodies were exploited in unethical clinical studies. In the autumn of 1932, fliers began appearing from the county health department and government in Macon Alabama, asking black men to get free testings for “bad blood”. The black men who signed up actually became part of a study analysing the effects of untreated syphilis. The unethical trials lasted up until 1972 and some of the men were left to die and go blind without any treatment.

Another example of this is James Marion Sims, known as the “father of gynaecology”, who invented the vaginal speculum which is still used today. He conducted his painful research on enslaved black women – with no anaesthetic.

More recently, there have been many anecdotal and documented horror stories of black people being mistreated in hospitals and not having their pain taken seriously. Annabel Sowemimo, a sexual and reproductive health doctor and gal-dem contributor, says there is a widespread belief among medical professionals that certain ethnicities feel less pain. It’s a topic that has been widely and globally reported on and informs a mistrust in the healthcare profession. Even in the 19th century in the US, there were reports of black pain not being taken seriously.

Dr Annabel explains that underlying scepticism and not knowing if the health system has black people’s best interests at heart is a relatable fear. “Yes health professionals want to help you, but are they collecting information for a trial study? Where is that information going? A lot of black communities have overlapping issues like immigration,” she says. “We saw very recently that the NHS was sharing information with the Home Office. I think things like that make people more wary.”

Reactions to vaccines seem to be something else that worries parents. The NHS does in fact state that vaccinations can have side effects, including a high temperature, headaches, and fatigue and in some cases an immediate reaction, anaphylactic shock, which can be lethal. Having said that, the NHS believes the benefits outweigh the side effects: “To have a balanced view, potential side effects have to be weighed against the expected benefits of vaccination in preventing the serious complications of

Having had a severe reaction to

“When she was pregnant with me they did not tell her my assigned sex on account of her blackness, wrongfully assuming that knowing that information would lead her to want an abortion”

“When she was pregnant with me they did not tell her my assigned sex on account of her blackness, wrongfully assuming that knowing that information would lead her to want an abortion or that I could come to harm being assigned female as a developing foetus,” Saskia says. “

Billie Laila, a jewellery designer and mother did, in fact, opt in for vaccinating her child. “I vaccinated my daughter until she had a life-changing reaction to the MMR at 12 months. Now I am educated on vaccines, I will never poison my daughter or myself again,” she says. “My daughter is nearly three and every day is a struggle for her. I already teach her about the dangers of vaccines and pharmaceuticals in general. She knows that natural remedies and homoeopathy are a safer and beneficial way of treating the body.”

I can’t lie, a part of me went into this a little annoyed I didn’t have all my vaccines and rolling my eyes at the sceptics, thinking it was extremely naive at best and dangerous at worst. But I’m an adult who has the choice of going and getting the vaccinations I see fit. Whilst I understand why some black parents are sceptical, I personally believe in having vaccinations – if it’s the choice between my child getting a temperature or getting measles, I know which one I’d prefer.

Having said that, I do agree in holistic healing for some health benefits and understand where medical intervention is needed in others. Either way, I can’t deny the historical suffering of black people at the hands of the medical profession. Moving forward, the medical industry has to take black parents’ concerns and fears seriously to build up a level of trust.