“Why do you put your hair in extensions, it’s so nice when you have it out!” says my white friend, grooming my fro with her eyes. “Yeah it’s so cool!” says another. I always noticed the twinge of watered-down jealousy, no, the fascination in her tone of voice that made me feel like an animal in a petting zoo.

Looking back now, I hated the way I would reply to such exclamations: “Yeah I know, it’s just too much to handle, like [laughs], you don’t even know, I have to like, plait it every night so I can actually drag a brush through it the next day [laughs again].”

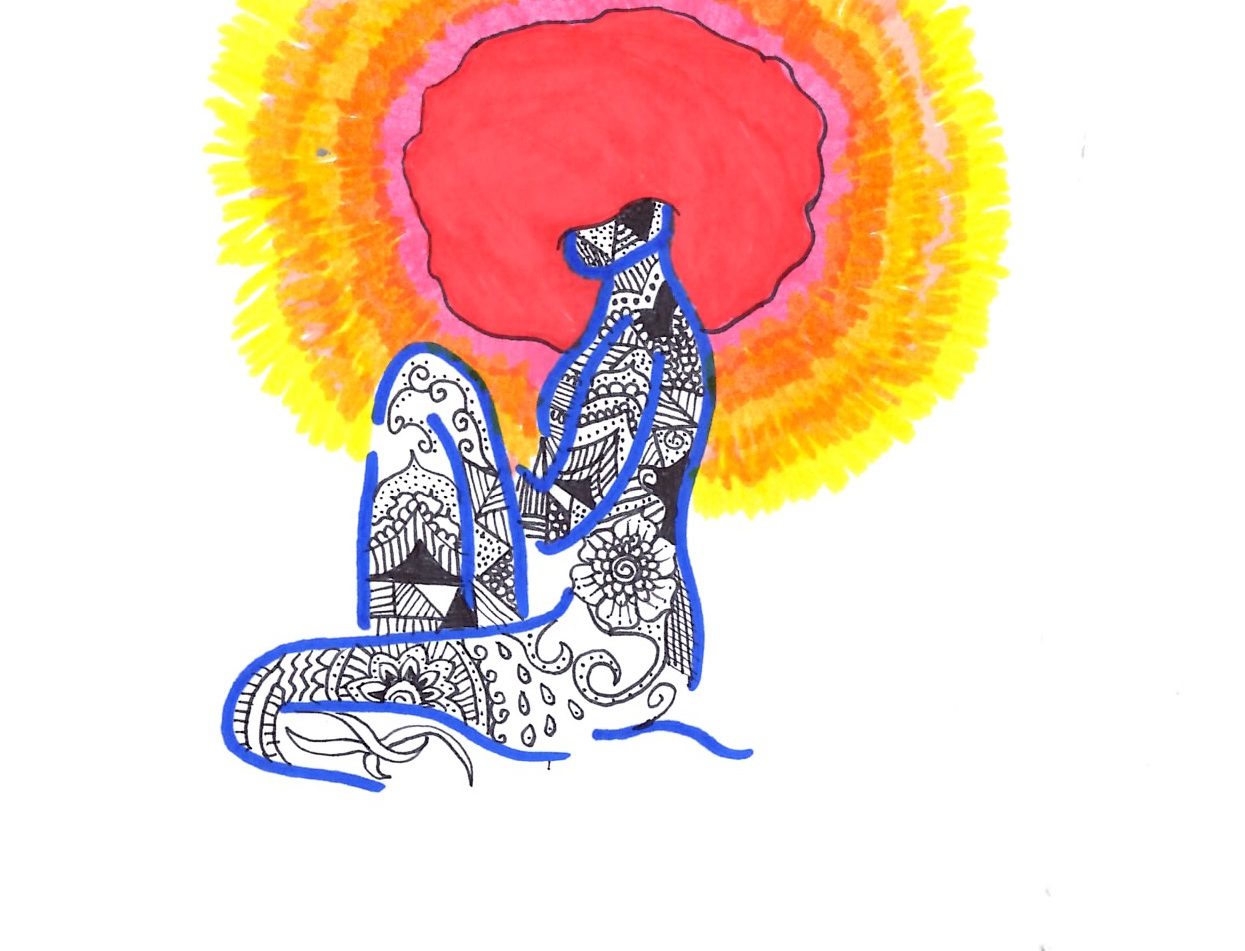

I used to talk about my afro as if it was external to myself, not something that grew from the roots of my scalp. Was it really “too much to handle” or was I just viewing it as a concept that I was too afraid to acknowledge was real? By describing it as “hard to deal with” and using all of these negative adjectives, I was personifying my hair as some kind of monster; something angry, loud and wild that lived in the roots of my hair, ready to growl and control my thoughts whenever it was let loose. It wasn’t something delicate, sexy or fashionable like the straight, flowery-smelling hair on the white women in the adverts. It was a political statement that, growing up, I felt I had to tame.

Washing my hair was always this long-ass process that I would describe to my friends during secondary school as a joke. The stories of my hair routines blurted out of me as if they were a source of entertainment, to humour my white girl friends who could only imagine the extensiveness of unloosing the braids, brushing out the hair, shampooing, conditioning, combing out, washing out, blow-drying and then…

“Why was it that it was only behind closed doors that I allowed myself these precious snippets of time to indulge in this secretive self-love?”

And then this part; the limbo stage. The “should I put in the hair now, or tomorrow? What am I going to do with this? Can’t leave it out obviously. It has to be covered up, to protect it” stage. It was an important time where I felt I had to confront my afro and acknowledge its existence, trying to avoid the slither of shame I knew I would feel when I was half-way done with my pack of braids, afro gone, afro concealed.

Despite the important decisions I had to make during that stage, at home I would shake it about, looking in every mirror I passed, eyes travelling up and around to admire the crown that was my hair. My parents and other family members would make comments about how lovely it was. My dad actually took a picture of it once, calling me “afro girl”. It felt good. I felt good.

Why was it that it was only behind closed doors that I allowed myself these precious snippets of time to indulge in this secretive self-love? It wouldn’t last forever; eventually I would have to go out and face the “big white world”. But here, in the safe-haven of a home where I was surrounded by other afros – covered by wigs or braids, shaved or locked, but afros nonetheless – I could love my own. I wasn’t embarrassed, I didn’t feel like a loud and incongruent being with a thunderous mane on my head; I was a beautiful, simple, ordinary black girl relishing the hair I was born with.

I’m lucky I can say this. I appreciate the family and home that I grew up in, that it wasn’t a hateful environment that would have stunted my growth and my escape out of the effects of institutional racism. I was afloat – even if I didn’t realise – in a sea of proud blackness, of experiences that paved the way for my own experiences.

“It’s something that all black girls have to go through. We are all guilty of abusive thoughts; being in battle with our hair, our shades, our bodies…”

Still now, at the age of 17, afro out occasionally, I think about my fro, sometimes resenting the thought having to twist it before I sleep, having to brush it out before I leave the house and all of the other trivial-but-on-the-spectrum-of-time-consuming things. But I always try my best to associate it with soft, positive images that make me love what grows on my head, and be proud of it.

It’s something that all black girls have to go through. We are all guilty of abusive thoughts; being in battle with our hair, our shades, our bodies, all in light of the White Gaze. It’s a weight that we carry with us throughout our lives and learn, sometimes with difficulty, to distance ourselves away from. It remains a part of us, even if it is just through painful memories and anecdotes.

One thing I am determined to do is change the way I talk about my afro. I have a five-year-old cousin, and I’m already planning the ways in which I’m going to make sure she sure as hell loves the blossoming bed of flowers growing on her head. I’m no longer going to season my words with subtle elements of self-loathing and feed it to white people, as it will only elevate them more. I realised that the more I joked about my hair, the more people were unable to respect it.

Whenever I do my hair, I massage certain sections of it, I sweet-talk it, I caress it. I do this to slowly heal the wounds that grew in there with every ounce of negativity that was applied to it.