‘When do I put my scarf on?’ – the forgotten magic and mystery of childhood sleepovers

Sleepovers are more than just childhood fun – for young women of colour they're a site for bonding, experimentation and the exploration of identity.

Micha Frazer-Carroll

07 Jan 2020

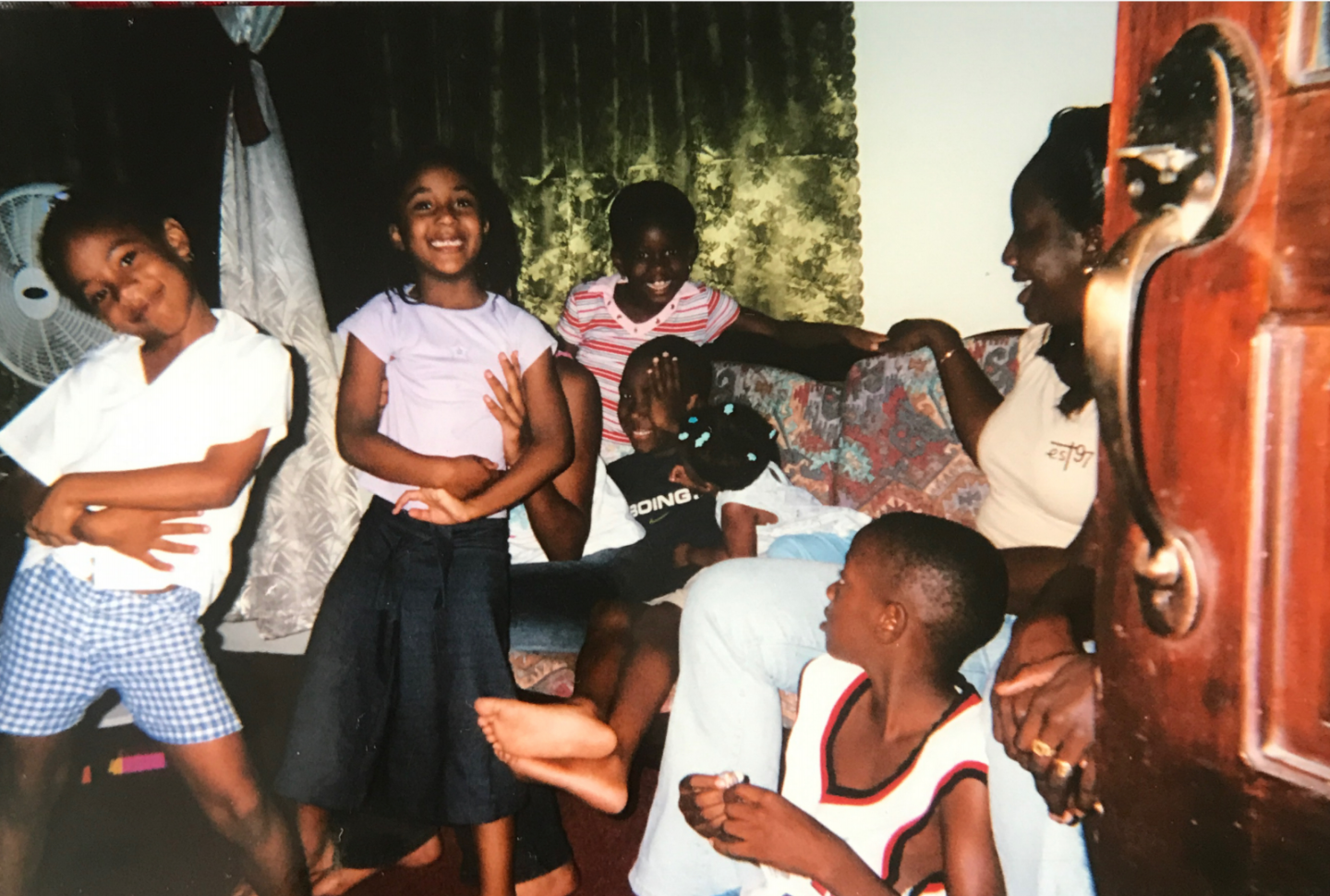

Photography courtesy of Micha Frazer Carroll

Tonight is the night. The anticipation has been mounting for weeks, but now the time has come, I’m not sure I can hack it. Lying in my best friend’s bedroom in my ruby-red pyjamas with the teddy bears on them, tears begin to roll down my cheeks, soaking into the silk pillow. I swallow my pride and say it.

“I…I want to go hooome!”

This is how my first sleepover went – or so I’m told by my mum, who had to come and collect a crying, snotty six-year-old at 10pm.

It was a poor induction into the world of sleepovers, but staying the night eventually became a staple in my child and teen friendships. Although we sometimes think about sleepovers as one of the more ordinary parts of adolescence, in many ways they are weighted with significance. Spending the night at someone else’s house is a milestone that happens when the lights are out – being brought closer together through giggles and whispers.

For many, they also brought racial, cultural and gendered dynamics to the fore – in a way we might not have seen in the light of day. Some of us weren’t allowed to go to sleepovers at all, and others who were had to navigate things like culturally specific bedtime routines, chats about boys and protective parents who wanted to know everything about the hosts. Sleepovers are often the first places we socialise away from our parents, which means discussions around sexuality come into the equation too. What was so special about staying at someone else’s house for the night? And what did sleepovers teach us about race, gender and growing up?

A site for bonding

Perhaps most obviously, sleepovers are a site for friendship-building and fun. In the early years, the fun that my friends and I had at slumber parties was regimented and centred on bonding; I remember countless sleepovers where we would create ridiculously detailed itineraries of what we thought we were supposed to get up to, which was probably modelled off of that slumber party scene from Grease, where the Pink Ladies prance around in fluffy slippers and rollers, smoke cigarettes and drink while Frenchy pierces Sandy’s ears. It was paradoxically both carefree, but also deliberate and self-conscious – we wanted to emulate a very specific type of frivolity, the kind we’d seen teenagers basking in on TV, without necessarily understanding why it was fun yet. I remember a friend and I once desperately straining to keep our bloodshot eyes open until midnight, because we had to tick “midnight snack” off our to-do list.

Dr Victoria Khromova, a child psychiatrist and parent coach, agrees that this kind of planned fun can be a big step in solidifying friendships. “Peer bonds are important in adolescence, and while the day-to-day of school is quite a structured environment, evenings and night-times can be quite unstructured. You have to tune in to each other to work out how you want to spend that time. This often takes relationships to a different level.”

Victoria adds: “Night-time is usually the time we need to feel the most safe – we have to be in a place that we trust in order to be able to sleep. Often kids will be able to function during daytime, but being away from parents at night-time is a much bigger step.”

“We were about eight, and the host’s bedroom was full of china dolls and we were all freaking each other out that they had haunted spirits”

Lucy Pasha-Robinson

The night does have a mysterious power over us as kids – I know I was still a little bit scared of the dark into my teenage years. But in the right conditions, this often made the thrill of a slumber party all the more exhilarating. Lucy Pasha-Robinson, who is 29, says her fondest childhood sleepover memory is connected to experiencing this sort of fear.

“We were about eight, and the host’s bedroom was full of china dolls and we were all freaking each other out that they had haunted spirits that would make them wake up in the night,” she says. “So by the time we went to sleep we were all whipped into a frenzy in that giddy, excited mood you manage to conjure as a child.

“After drifting off, in the middle of the night, we were awoken by one of the girls sleeping in the middle of the room. She was sitting bolt upright, eyes shut, and speaking in what we thought were ‘tongues’. It was also the golden age of Harry Potter, so we may have been influenced by The Chamber of Secrets… Cue lots of screaming, crying, and some angry parents.”

A space to practise growing up

I was allowed to go on sleepovers, but not without an intense list of ground rules, which included an interrogative vetting procedure fit for MI6. My mum would need to know a number of things: what is the household like? Are there any brothers or dads? Will I be supervised? Then she’d call up the parents – so embarrassing. By the time I got to my friend’s house, it felt like a huge victory, despite the fact that I’d then have to text my mum with regular updates about where I was, who I was with, and what I was doing. It was an elaborate dance, but what we were really doing was negotiating the process of me becoming a separate and autonomous person to my parents.

Sleepovers facilitated a novel kind of identity exploration – unsupervised, we could engage in entirely new activities, personas and ideas, however tentatively we dipped our toes. I remember nights where we’d huddle round on blow-up mattresses and sofa cushions and practise kissing (although I always sat out), rigorously curate our “top five” lists of fittest boys, and in later years, grill the only person in the room who’d had sex on exactly what it felt like. Once a friend and I bought condoms and rushed them home like a secret stowaway, ripping them open to inspect during the sleepover that followed.

Sometimes that experimentation was also aesthetic – painting nails, braiding hair, or piercing things. Simran Maini, a 31-year-old sleepover veteran, had an older sister who served as a gateway into the world of glam, which was easier to explore away from the heavy, watchful gaze of parents. “She’d let me take her make up bag and me and my friends would put make up on each other and wear her clothes. I remember she had this pair of knee-high boots that were absolutely massive on me… We did a photoshoot – there are these awful photos where I’ve got my hair down with a really visible kink in it because it’s just been taken out of the ponytail and loads of lipstick on.

“My dad was the one who went to get them developed – I wonder what he was thinking when he gave them back to me.”

Being far from home

As well as an opportunity to experiment, for many of us, sleepovers also served as an immersive step into the world of whiteness. As a kid, I remember being equal parts baffled and intrigued as to how other families operated – even the smallest differences, like wearing shoes indoors, or sleeping in late without being told to get on with doing housework.

Not long after my harrowing first sleepover experience, I remember being at a friend’s house and watching her scream “I hate you!” at her mum. Is this how some people live?

Different modes of communication felt alien to Simran too. “I come from a Punjabi family where everyone is super loud. The way my parents talk to each other would sound like they were shouting to my English friends, when actually they were just having a normal conversation,” she says. “The first time I went to my best friend’s house, it was very formal and polite – and she had a pony.”

“The way my parents talk to each other would sound like they were shouting to my English friends, when actually they were just having a normal conversation”

Simran Maini

Lucy, who is mixed race, says that the closeness brought about by sleepovers made her more aware of racialisation and her body. “Sleepovers were spaces in which my mixedness was made apparent to me. Noticing that my friends had pink hands, pale nipples and fine, silky textured hair. Realising that most of my friends had parents who were both white.”

There are also culturally relative parts of bedtime routines that felt odd and awkward when suddenly inserted into a sleepover setting – sometimes the most intimate and private parts of our home lives. “I had a very hard time figuring out… at what point in the night do I put my scarf on?” says Manna Zel, who is 21. I also relate to this – a white ex of mine once remarked that using my tights as a headscarf was “hilarious” the first time he saw me do it before climbing into bed. But to me, it felt like the most mundane thing.

For Manna, the issue made her feel vulnerable, and also presented a conflict: “There were times that I wouldn’t put on my scarf or my bonnet because I thought I would look stupid. Then I’d wake up in the morning and my hair would be messed up and I’d be upset at myself.” This resulted in Manna later waiting until the lights were off to secretly pop her scarf on, even into her college years.

‘But what’s wrong with our house?’

But perhaps the biggest cultural difference brought to light during sleepovers was the issue of attendance in itself – many kids of colour weren’t allowed to go.

Sharan Dhaliwal, a 35-year-old writer from London, knew that struggle throughout her adolescent years. “My mum generally didn’t trust any other families – everyone was a potential murderer or something,” Sharan says. “She was always saying things like, ‘But what’s wrong with our house?’” One day, without telling her mum, Sharan sneakily went along to a friend’s house after dark. “I eventually left, but when I checked my phone I had millions of missed calls and messages. When I got home, Mum was in tears and had called the police. She actually said ‘I thought you were dead!’ I was like, ‘It’s 8pm.’ The police stood there, laughing.”

While Sharan giggles as she recounts her mum’s response to an innocent 8pm walkabout, for others, being held back from sleepovers had complex repercussions. Zara, who is 30, says that being excluded from the events as a teenager deeply affected her.

“When I got home, Mum was in tears and had called the police. She actually said ‘I thought you were dead!’ I was like, ‘It’s 8pm.’ The police stood there, laughing”

Sharan Dhaliwal

“Whenever I would be out late with my friends, I would grapple with the turmoil of knowing what was waiting for me at home. My phone would be blowing up by the end of the night,” she says.

“Not staying away from home hugely affected my ability to do so in later relationships… I became so accustomed to being in my personal space that now I find it really challenging and exhausting to adapt. This resulted in exes taking issue with my inability to stay over last minute or for long periods of time, and stunted intimacy in those relationships.”

A rude awakening

Despite some of us never being allowed to go on sleepovers as adolescents, Simran remembers them with a gleeful twinkle in her eye. She has kept the tradition alive with her four best friends. The group mostly host them when one of their husbands is out of the country – “It’s like the whole ‘free yard’ thing,” she laughs.

“We’ll get in our pyjamas, get out the prosecco, go through old videos and photos, and complain about our husbands.

“Especially as you grow older and life takes over, people get so busy – and we’re a married bunch now – so it means a lot. I think it’s something we’ll continue to do no matter what.” But Simran’s group is the exception to the rule. For many of us, the practice of sleepovers fizzled out as adulthood loomed, or at best, eventually changed beyond recognition.

A tweet by @lusxt that popped off in 2018 read: “sleepovers when ur small: omg stop laughing and go to sleep you guys!!! sleepovers now: I don’t think I’m capable of love”. This definitely resonates with me; nights that used to be full of getting hyper on Haribo and playing never-have-I-ever have now been replaced by rubbing off your eyeliner, lying in the dark after a long day or a night out and talking about work and relationships. The sad reality is that the secret, mythologised fun of the sleepover does – for most of us – come to an end.

“These days it’s more of a convenience thing,” says Donna Salek, 22. Maybe some of the mysterious magic falls away when you gain the independence of living alone – and also when staying up all night is more of a familiar concept. Donna adds: “After all, uni is just like a big sleepover anyway. But when we were younger, sleepovers were almost like a tiny vacation – that feeling of freedom.”

And I know exactly what she means – that buzz of pure excitement that came with an old-school sleepover at someone’s parents’ house; a combination of closeness, mischief and the prospect of unending quality time. “It’s about knowing that for once, finally it’s not going to get cut short – the fun’s going to continue until the next morning,” she says.

Even for those of us who continue the ritual, I wonder whether it’s possible to fully recreate that childlike feeling. It’s like a little dusting of magic lined those early hours; joy folding out in front of us, in time that had always gone untouched.

Taken from gal-dem’s print issue UN/REST, on sale now