“A lot of people don’t know what Islam really is”, I was once told, at a table for my university’s Islamic Society. “It’s a blessing to teach them”.

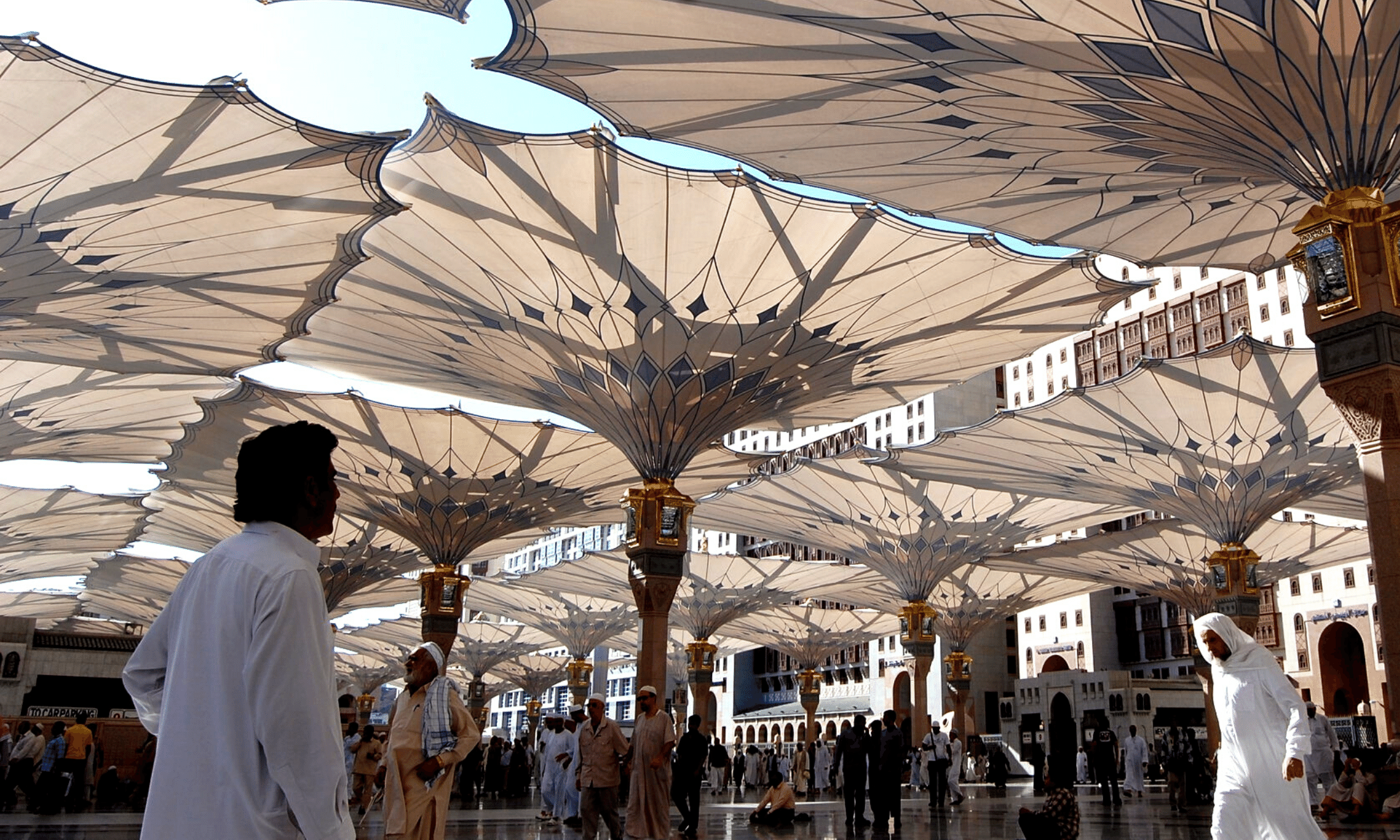

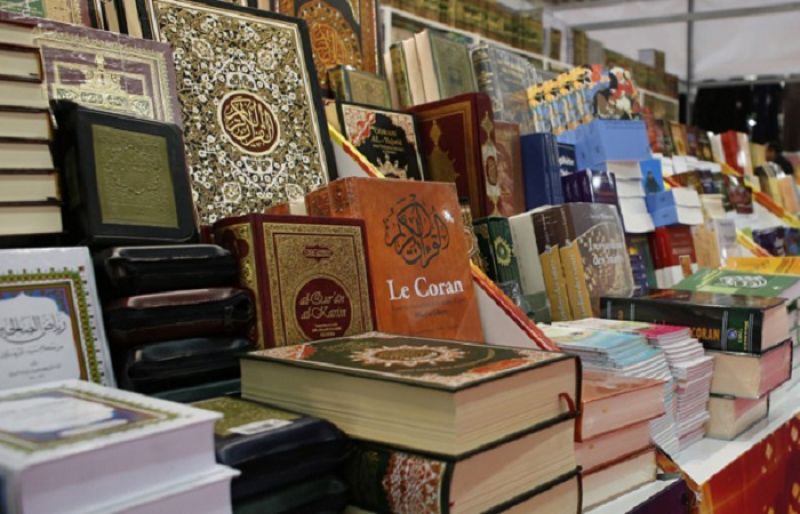

While this particular crowd was Sunni Muslim, there would be other times when the school’s large Shi’a Muslim groups would also be “tabling”. People would be treated to a collection of material explaining the basic tenets of Islam, and why it’s different from what they’ve heard before. Obviously, as an overarching goal, this should be supported. Muslims should be given space to discuss Islam themselves, as an alternative to how it is framed by The Sun, The Daily Express, and The Daily Mail, as well as by increasingly savage politicians.

The problem is that these seemingly harmless events, including Islam Awareness Weeks taking place at campuses across the country, often have highly questionable politics themselves. When an Islamic Society member tells a non-Muslim “what Islam really is”, they are also defining it for themselves, and making an argument to the Muslims around them. Often, this means elevating their own standing as “positive representatives of Islam”, with a narrow idea of what that means, and to the exclusion of Muslims who may not understand themselves that way.

This behaviour reflects a larger political demand linked to the War on Terror, which is that Muslims must differentiate themselves from the “Bad Muslims” in revolutionary jihadist groups like the Taliban, Boko Haram, and Islamic State. Increasingly, the only way for racialised Muslims to do that, especially if they are not heterosexual males, is to brand themselves as one of two types of “Good Muslims”: either Pious Muslims, like the people tabling, or Anti-Muslims, that both challenge and mirror them.

“When an Islamic Society member tells a non-Muslim ‘what Islam really is’, they are also defining it for themselves, and making an argument to the Muslims around them”

When a Muslim “explains” Islam to a non-Muslim, they’re making themselves a representative of the faith, and arguing that their views are the most legitimate ones. Let’s say an Islam Awareness Week poster says, “Muslims believe that Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) is the last prophet sent by God”, in front of a Pious Muslim who shows it to the audience. While it may seem like a basic fact about Islam, it’s only that simple for Sunni Muslims that have a specific relationship to the religion. Ahmaddiya Muslims, for instance, have a completely different understanding of prophethood, in which Muhammad is only described as the final “law bearing prophet”. A Pious Muslim may also say that Muslims are not allowed to eat pork, drink alcohol, or have sex before marriage, when in reality, Muslims frequently do all of these things without issue.

Effectively, this process erases the huge number of ways that Muslims interact with Islam, that is if they want to interact with it at all. Good Muslims, that practice Islam “properly” are said to be like the Pious Muslim, who quietly elevate their own social standing. As a result, these Pious Muslims become the ones who get to claim that they are “True Muslims,” while taking prominent leadership roles in campus life, whether in Student Unions, political action groups (especially ones that deal with Palestine, Syria, and increasingly Yemen), or the Islamic Societies themselves. Muslims that have different understandings of their identities end up getting treated like members of the Taliban, in that they are treated as religious deviants who are “not real Muslims”. While Pious Muslims tend to be men, increasingly, many are also women, who take care to promote themselves as modern, independent, and trendy Islamic Feminists, that nonetheless have a specific relationship to Islam.

Pious Muslims also respond to widespread political scrutiny, as a result of the dual challenge of terrorism and Islamophobia, by sticking to “non-radical” liberal politics. This means that if politics take place at all, it will be engaging with institutions like prominent civil society organisations, and the major political parties in parliament, rather than leftist and grassroots alternatives. Often, their exclusionary sense of Muslim community is partnered with conservative views on the economy, that can be described as Islamic Neoliberalism. Pious Muslims often lean towards using an Islamic economic vocabulary to support laissez-faire capitalism, interpreting concepts like zakat to mean “charity” rather than “wealth redistribution”. Eventually, these political positions allow them to expand their personal power even further by making them seem like an engaged liberal Muslim citizen and an ideal partner for institutions, which see them as useful “go-betweens”.

Of course, it’s important to remember that Pious Muslims are not the only kind of Good Muslims that have emerged lately. While organisations like the Muslim Council of Britain have grown in power and influence, they are paralleled by Anti-Muslims who will claim to be coming from within the religion. Effectively, their Islamophobia is far more effective, because of an idea that Muslims can’t be racist and Islamophobic to each other. Organisations like the Council of Ex-Muslims will cast Islam as a threat to “reason, universal rights and values, and secularism”, using language that is difficult to challenge because of the legitimacy that they gain with their Muslim identities.

“…this process erases the huge number of ways that Muslims interact with Islam, that is if they want to interact with it at all”

Anti-Muslims have frequently exploited LGBTQ politics to make their point, though importantly, it is also common for Pious Muslims who are LGBTQ to make constant references to their practicing of Islam to seem more legitimate. Anti-Muslims tend to focus their criticisms on the most conservative Pious Muslims, who in addition to terrorist groups, are said to be the “True Muslims,” with everyone else being ignored. This feed into the imposed representative status of Pious Muslims, and also, it means the Anti-Muslims can position themselves as counter-representatives.

Indeed, just as Pious Muslim clerics will meet with Pope Francis at the Vatican, Anti-Muslims will call themselves “Atheist Muslims” and condemn revolutionary jihadism on the same platform as obvious racists like Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris. Ultimately, Pious Muslims and Anti-Muslims are both seeking to represent Islam in a politically safe manner, usually for their own benefit. Either way, Muslims are constantly forced to explain themselves, in relation to Islam. But they can only do that in a limited number of ways. Either you’re politely religious like the Imam, politely anti-religious like the self-hating Atheist Muslims, or you’re suspected of wanting to join Al-Qaeda.

For many Muslims, on a personal level, this discussion totally overstates the importance of Islam in people’s lives. Indeed, Muslims who want to relate to people in other ways, like class and feminist politics, or literary and music interests, start to feel lonely and as though they’re doing something wrong. However, these alternate ways of forming communities are essential, in order to challenge assumptions about how Muslims are supposed to behave. It’s not that Islam is good, or bad. It’s not that one interpretation of Islam is more correct than another one. It’s that the broad diversity of people’s ways of looking at the world, and lived experiences, fly against panicked attempts to box everyone in. Muslims can be, and are, almost anything you can imagine.