When Facebook events for women’s marches started popping up on my news feed, I felt an uneasiness. Despite the protests being described as inclusive, I already knew which women they would inevitably be centred on. And what I couldn’t shake was that 53 percent of these women in America had voted in a deplorable demagogue – a man who is merely a symptom of the far more pervasive evil of white supremacy – a small detail that many white feminists seem to wilfully overlook. As succinctly put in a Twitter thread by journalist Christiana A Mbakwe, “the elephant in the room is that there’d be no #womensmarch if all women voted for Hillary Clinton like black women did.”

94% of black women showed solidarity towards HRC. They did their bit. Other women let them down. #womensmarch

— Christiana A Mbakwe (@Christiana1987) January 21, 2017

And therein lies the problem for many people of colour: how does a black woman reconcile getting behind a women’s protest when 94 percent of black women went down to the polling stations and cast their lot with Clinton only to be thrown under the bus by a majority of white voters who could not see beyond their own interests to think, for one second, of the fear that a Trump presidency might invoke in people of colour, queer and LGBTQIA+ people, trans people and immigrants? What do you do when you’re expected to swallow your bitter disappointment and stand shoulder to shoulder with many feminists who only seem to stand up and make noise when they have a vested interest in the matter at hand? Like Mbakwe says, where were all these women when we lost Sandra Bland?

Some of the fundamental problems with the Washington march date back to months before it took place. Brittany T. Oliver, a women’s rights activist from Baltimore, voiced frustration with the Women’s March on Washington co-opting messaging from two prominent events of civil disobedience in black history: One Million Women, led by black women in response to feminists ignoring the experiences of people of colour in 1997, and the well-known March on Washington in 1963. Oliver states “politically co-opting efforts with “ALL WOMEN” and “ALL VOICES” is merely an attempt to erase the specific needs of people of African descent.”

Similar sentiments were echoed by those involved with the march at state administrator level, with former Louisiana state admin Candice Huber stating that many had issues with the chosen name of March on Washington and when women of colour called spoke up, “the national organisers refused to listen… In response, they were blocked from the secret FB group and their own event pages and their comments deleted.” These weeks of conflict even led to some organisers stepping down as a result.

The London solidarity march was also no stranger to controversy as they were called out for tweeting the UKIP, the radical right and “unashamedly unicultural” political group, and inviting them to “stand with us for #equalityforall”. To be able to overlook the racially coded language used by this party during conversations on immigration, nationalism and Britishness is a luxury not afforded to people of colour and to invite them march for equality is utterly laughable.

Though they issued messages of inclusivity and diversity, the Women’s March on Washington, and its solidarity marches, were already setting a tone of apparent ignorance towards complex issues and concerns posed by other marginalised groups. Originally organised by white women, as stated on the march organisers’ website, there were valid concerns with regards to intersectionality. As members of marginalised communities know all too well, feminism without intersectionality centres white straight cis able-bodied women and as a result, the “one size fits all” values become performative at best – some of which could be witnessed on Saturday.

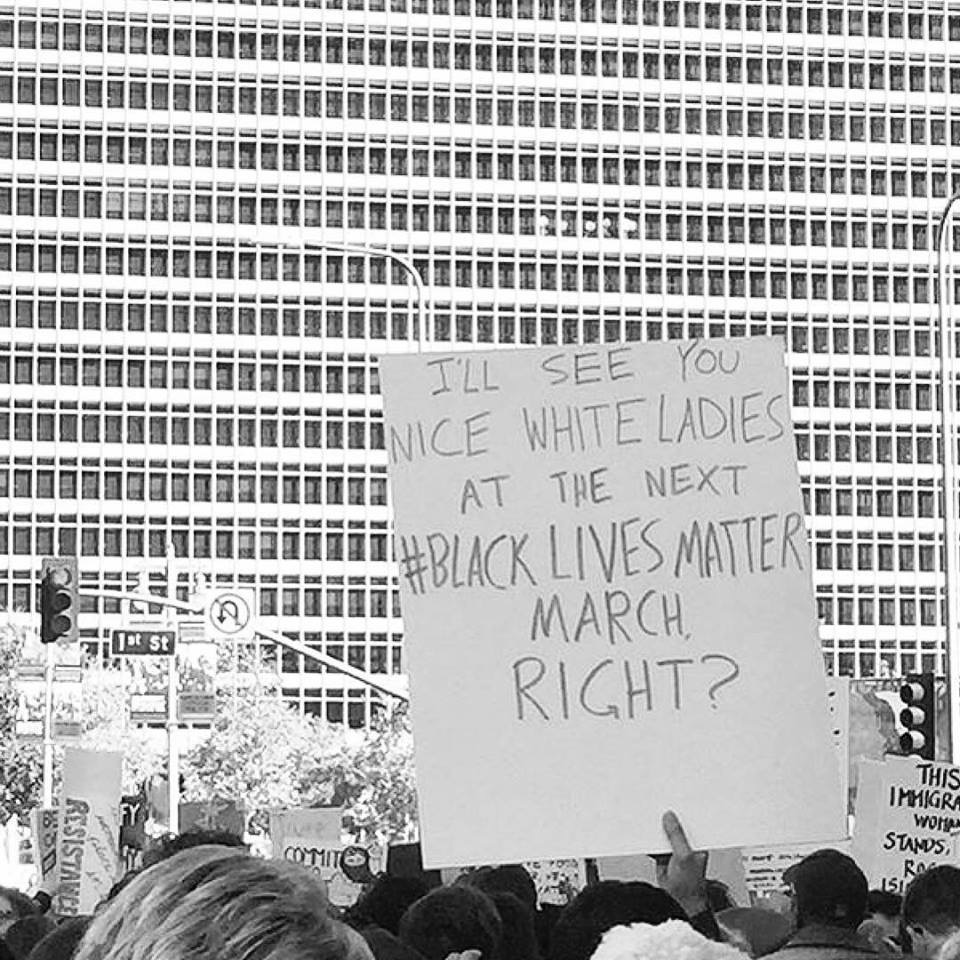

THIS SIGN IS STRAIGHT UP FIRE pic.twitter.com/X25iLAj6eV

— ㅤ (@thirIstyIes) January 21, 2017

Slogans and placards with the words “pussy” and “vagina” as signifiers of womanhood, while provocative and memorable, remain staunchly cis-centred and immediately exclude trans and genderqueer people – not all women have vaginas. And while there may be no malicious or exclusionary intent as some may believe that use of “vagina/uterus” is valid in support for organisations like Planned Parenthood, it treads dangerously along the TERF (trans-exclusionary radical feminist) line where girlhood and womanhood is centres around genitalia, leading to members of the trans community deciding not to go in order to avoid TERFs and trans-exclusionary messages.

Women are posting messages on pads #WomensMarch pic.twitter.com/UL5evnTbjV

— Colleen Hagerty (@colleenhagerty) January 21, 2017

Another example of feminist grandstanding from the women’s marches could be seen with political statements being made with sanitary pads. Many were pictured writing messages on sanitary pads such as “bleeds proud”, “grabs back” and “no pussy, no power” and sticking them to walls. When I first saw these pictures, they immediately made me think of solidarity safety pins, with their grand yet hollow symbolism that offers nothing tangible beyond a nice picture and maybe a think-piece. Additionally, when you have homeless women and femmes who have limited or no access to menstrual products, leading to the necessary implementation of projects such as The Homeless Period, it seems like such a bitter waste of sanitary pads just to make a gesture.

It’s impressive to see how many turned out for the marches, with 20 countries seeing protests and it being estimated that half a million people partook in the march on Washington. But, as put by UK activist Tas Mia in a Facebook status, “I’m glad if #womensmarch was your first march, the first action you have been inspired/move to take action and show up. But know this, many of us have been marching and resisting for quite some time…the #womensmarch cannot be the beginning and end of where your passion and activism lives; that isn’t enough.”

While the Women’s March on Washington, and all the adjoining solidarity marches, make a huge statement, that is all it will ever be without a long term continuation plan that involves complex discussions on race, power and privilege that will make a lot of people uncomfortable. Taking accountability is always uncomfortable but it’s necessary because, like Tas Mia says, “it’s all too easy to condemn Trump and still be wilfully ignorant to the ways we all (some more than others) play a role in upholding the very same structures that allow white supremacy to flourish.”

I did not take part in the Women’s March because, especially after the last year that saw the ever-pervasive nature of xenophobia and racism lead to major decisions like Brexit and Trump’s election, I am distrustful, disappointed and disheartened by the way in which intersectionality and accountability feel like suggestions rather than necessities.

It’s a shame 100,000 British women never showed up for Sarah Reed or the other cases of police brutality in the UK. #JustSaying

— Tobi Oredein (@IamTobiOredein) January 21, 2017

But, women of colour voicing their frustration with the women’s marches is not us trying to be agitators or play “who struggles more?” The idea of shared sisterhood is little more than an abstract concept or even a myth when the unique nuances, worries and experiences of different women aren’t taken into consideration. We’re asking you to acknowledge that it’s hard to pick up the call to march next to people whose voices can go silent when it comes to issues that affect the rest of us.