Image: Michelle Wong

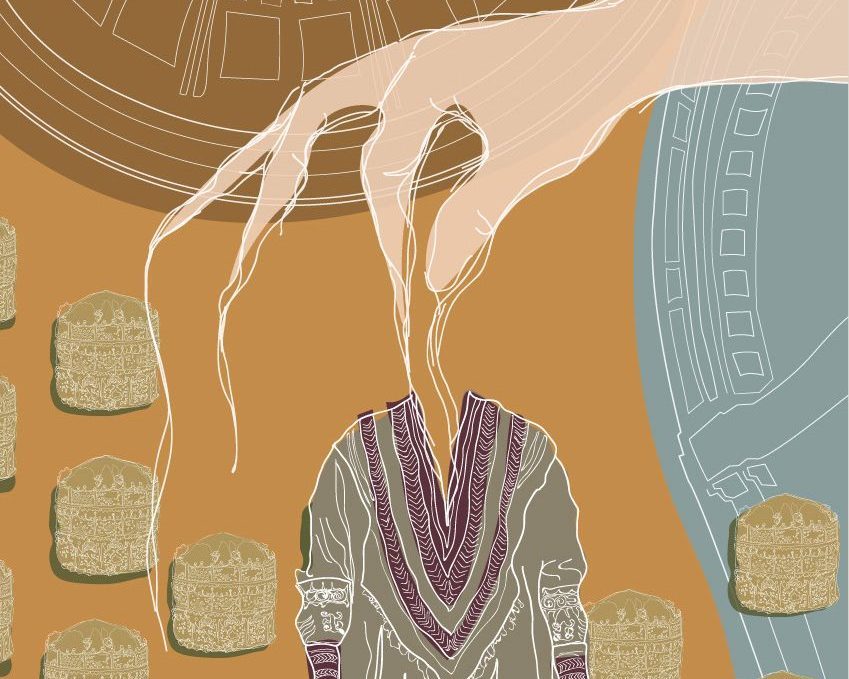

You know the scene. Killmonger peruses the artefacts in the fictional Museum of Great Britain, enquiring about the historical items in the West African exhibit. “How do you think your ancestors got these?” he asks. “You think they paid a fair price?”

“Or did they take it, like they took everything else?”

There were many moments that got the Black Panther crowd whooping and cheering in cinemas in February of this year, but this outburst really touched a nerve. Rarely do you get a mainstream film that acknowledges the unsavoury history of the items on display in museums, or of the nobility glorified within the UK’s prestigious institutions.

Marvel Studios

Over the last year there have been calls for the repatriation of artefacts from institutions, as some countries have asked for the return of sacred items that were looted hundreds of years ago. Like when Nigeria requested the return of the Benin Bronzes, two hundred items of treasure that were taken by British soldiers after an attack in 1897 that killed thousands. The metal plaques once lined the walls of the royal palace of the Kingdom of Benin, which is now part of modern-day Nigeria. When the country asked for the items that were dispersed between exhibits in London, Oxford and Cambridge, the British Museum considered giving the items back to Nigeria on a loan basis.

“We try to be transparent about the ways in which objects have been collected, particularly during the colonial period. Any film that draws attention to the importance of these objects is to be welcomed,” a representative told artnet News at the time.

While it seems Nigeria may be ready to accept a loan as the final solution, some countries are not as understanding. There is a growing conspiracy that the Chinese government was behind multiple heists of Chinese artefacts over the last decade as thieves targeted looted items. Since 2010, the Chinese Pavilion on the grounds of Stockholm’s Drottningholm Palace, the China Collection at the KODE Museum in Norway, the Oriental Museum at Durham University, Cambridge University’s Fitzwilliam Museum, the Museum of East Asian Art in Bath, and more, have all been targeted in highly professional robberies straight out of a Hollywood scene. A haul in the Château de Fontainebleau, just outside of Paris, saw the other 1,500 rooms go untouched while items taken from Beijing’s revered Old Summer Palace in 1860 disappeared. The presence of these items in European institutions had been a contentious subject for decades.

Steve Tatum, via Flickr

The Black Panther scene is thought to be a clear nod to the British Museum, but it could also apply to somewhere like the V&A in Knightsbridge. The museum recently came under fire for its ‘Maqdala 1868’ exhibit of Ethiopian treasures, which includes a gold crown, a royal wedding dress, and jewellery – all taken by the British army during an expedition that left hundreds dead. Activists were again dismayed when Ethiopia’s repatriation demands were met with the institution’s suggestion that they could give it back on loan.

Janet Browne, the African Caribbean Officer at the V&A explains that she sees a long loan as a good temporary resolution, rather than an insult. “It wasn’t to shut anybody up. It was to say: ‘Well we kind of agree with you and this is what we can do. If you want it, you can put it on display in Ethiopia so people can see it in an institution and continue to campaign for restitution,’” she says. It could be years until a claim for repatriation sees any success due to the stringent administrative procedures that happen behind closed doors. “It’s not that we as a team don’t empathise with Ethiopia. But we can’t just pack it up in a box and then give it back because we’d all be sacked. However, we can give long loans where it would be years before we saw the items again.”

“Hundreds of exhibits in the West once belonged to people of colour, and the power of some of the people standing proudly in portrait halls was largely built on our backs”

A large part of Janet’s role over the last 12 years has been ensuring that the V&A consults the communities who are connected to the works on display. “Given the background of the material, it had to be democratic with people who have a stake in how it was presented. We had people from the Ethiopian community, the Anglo-Ethiopian community, the Rastafarian community and people from the Tewahedo Church because the nature of some of the materials is religious give us guidance and advice on that material.”

Over her time working in the art world she’s seen a push to widen the audiences of institutions, but thinks sometimes these gestures feel “tokenistic”. “It’s important that white people understand the part they played in erasing other people’s histories. I’m trying to honour that history but I’m still working in an imperial building with a colonised narrative. So, you know, you go around the museum, you’re looking at things, but you’re not really looking at them.”

Paul Hudson, via Flickr

For those of us whose parents filled in the gap left by the woeful history curriculum of British schools, walking through exhibits can be infuriating. So many heroes, explorers and monarchs are centred in these spaces, where there are barely any brown faces, yet their histories and ours are so intimately intertwined. Wealth that was built off the back of theft or enslavement of others is flaunted and the evidence laid bare in glass cabinets in our museums, without a mere mention of the dark and painful stories.

It’s a feeling that sits with you as you walk around the National Maritime Museum, one of several institutions where Alice Procter runs Uncomfortable Art Tours. Since last year, the young historian has been trying to make people unlearn the hero narrative often projected onto the days of empire, exploration and enlightenment. She points to portraits and tells the story of how Elizabeth I, with her hand on the globe, set the wheels in motion for colonisation and slavery. Or how the South Sea Company’s coat of arms on display was purposely made to look like the company had more to do with fishing than with the trade of enslaved lives.

“The evidence is laid bare in glass cabinets in our museums, without mere mention of the dark and painful stories”

“I had a big problem with the way Captain Cook was portrayed in the recent British Library exhibit,” she says. “They gloss over his death in Hawaii, when actually he took the ruling chief of Hawaii hostage, so they killed him. That was a technique he used on a lot of his voyages,” she explains as we make our way around the finely decorated building in Greenwich. “I’ve spent the last six years of my life trying to unlearn the narratives you’re taught in school, to instead scrutinise our ‘heroes’.” While working in the art world she has encountered the narrative that museums should be neutral. “But who likes a neutral museum that doesn’t speak up against political injustice, historical violence? Nazis and the far-right would argue for a ‘neutral’ museum. More galleries need to realise that they can either appeal to racists, and the wilfully ignorant, or they can appeal to everyone else and to people of colour whose truths deserve to be seen. They’re going to have to pick a side.”

SouthEastern Star, via Flickr

She continues: “Museums are obviously afraid of opening the door because they’re worried that they’ll lose everything. But there are ways of telling these stories other than with stolen objects – museums used to have human remains on display, but you may now see a 3D scan instead.”

Alice is calling on museums to take some responsibility in pushing the narrative forward with her ‘Display It Like You Stole It’ call to arms. “Tell the story honestly, and represent these narratives fairly and justly. If you won’t give the Benin Bronzes back, you’d better fucking have a Nigerian curator to talk about that history.”

The truth is the world wonders of hundreds of exhibits in the West once belonged to people of colour, and the reputation and power of some of the people standing proudly in portrait halls was largely built on our backs. It’s not just the plundered countries that UK galleries and museums owe the truth of these items and portraits to; Britain is having an identity crisis, and it’s impossible to divorce knee-jerk reactions like Brexit, the rise of the far-right, or rabid xenophobia from our extremely blinkered view of British history.

If we’re unable to understand the past, then we’ll neglect to have the tools and knowledge to challenge the calls from the far right to “take back control”. These institutions could serve as vital monuments to the horrors that Britain’s ego has already inflicted on the world. It might be time our museums told the truth instead of an edited fairytale.