Last month, Trump signed a wave of executive orders that directly targeted Muslims and immigrants living in or hoping to come to United States. Portions of the affected communities in the US have mobilized in unprecedented ways against these actions, and received unprecedented global support — but both the fact that this mobilization was so groundbreaking, and because it was not entirely inclusive, should unsettle us.

I am alluding to the pervasive anti-blackness that has shaped both the executive orders and the so-called “progressive” activism against it. Anti-blackness forms the bedrock of the United States’ longstanding legality of exclusion: from the Three-Fifths Compromise of the Constitution, to restrictions on suffrage, discriminatory lending practices, and today’s limitations on naturalization and immigration, blackness has had to endure assault after assault. But when considering the vast historical background that enabled last month’s executive orders, it is worthwhile to look back to 1996.

Last April, Black Lives Matter Co-Founder and Executive Director of the Black Alliance for Just Immigration Opal Tometi wrote an op-ed for TIME Magazine pointing out that in September 1996, the Clinton Administration passed the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA) which, among other things, re-categorized non-violent crimes as sufficient legal grounds for deportation. This was also extended to apply to immigrants with legal resident status. Previously, those without citizenship who were sentenced for five years or more for committing a crime in the United States would be eligible for deportation. But the IIRIRA adjusted this so that any non-citizen who was even accused of a crime that could potentially carry as little as a one-year sentence could now be deported. These crimes included minor marijuana possession, traffic offenses, perjury, and disorderly conduct. In other words, carrying a few joints could result in a slap on the wrist for American citizens, and deportation for the undocumented.

On January 25, Trump signed the “Border Security and Immigration Enforcement Improvements” Executive Order. This represented an expansion of the already staunch 1996 regulations. Trump’s order allows law enforcement to detain any person who they simply suspect of breaking any law, and, while they are being held, to determine their immigration status on an expedited basis. The order also calls for a closer relationship between ICE and local police forces, so that investigations and deportations can be more rapidly enacted.

On that same day, Trump also signed the “Enhancing Public Safety in the Interior of the United States” Executive Order. This prioritized the deportations of non-citizens convicted or even charged of any criminal offense, which could include a crime as inoffensive as driving without a license.

Finally, the Executive Order entitled “Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States” but a temporary ban on entrance into the United States for non-U.S. citizens who were nationals of one of seven Muslim-majority states. Two of those, Somalia and Sudan, have populations with black majorities.

Anti-blackness is central in all of these policies. The Black Alliance for Justice, a racial justice and migrant advocacy organization, elaborates on this in their recent report, “The State of Black Immigrants: Black Immigrants in the Mass Criminalization System.” The authors argue that because racial profiling disproportionately targets black people in the US, black people are more likely to have criminal convictions or be stopped by police for “routine” checks. Currently, black people are more likely than any other demographic to be arrested, convicted and imprisoned in the United States. Due to these new immigration policies that are based on detaining potential, accused and charged criminals, black migrants are at a greater risk of detention and deportation than any other unnaturalized migrant group. Before the executive orders were signed, the Black Alliance for Just Immigration noted that of the total undocumented population in the United States, only 5.4% was black. However, black people made up 20.3% of all migrants facing deportation on criminal grounds. Now that law enforcement’s abilities to detain suspected criminals has been broadened, the numbers of black migrants affected will swell at a rate that will be unknown to other migrant groups.

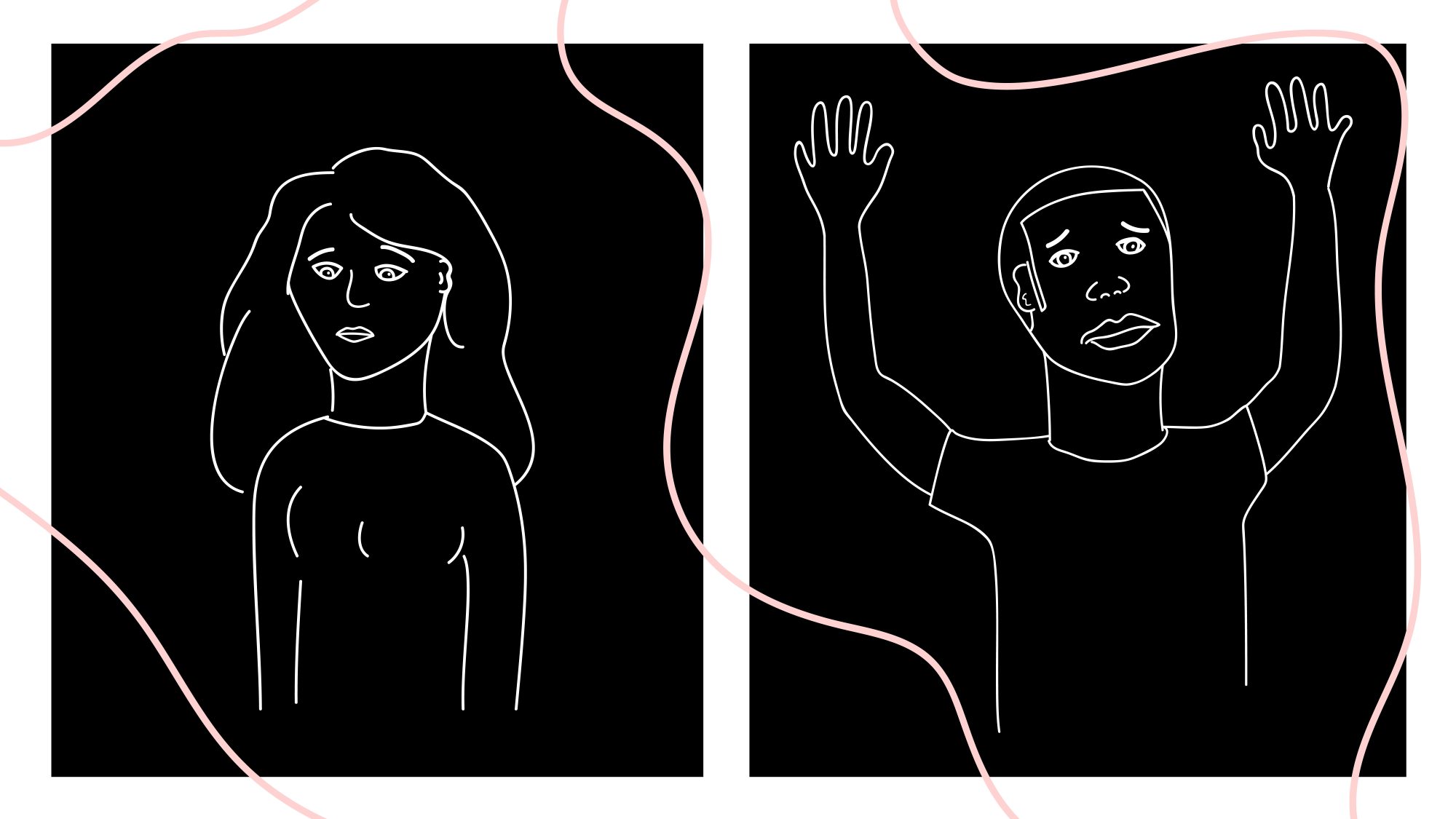

And yet, despite the clear anti-black nature of these U.S. American policies of exclusion, and the anti-blackness that contributed to the addition of Somalia and Sudan to the travel ban list, black identity has been carefully eliminated from the debates and popular resistance movements that have emerged in the last few weeks. Non-black (and especially light-skinned) Muslims, Arabs, Persians, and Latinx peoples have become iconified as the face of the struggle, and have also mobilized in unprecedented ways on behalf of this struggle.

A 2011 Pew Center Survey reported that 23% of Muslims that are U.S. citizens identified as black, and there are undoubtedly many more black Muslims in the American immigrant community who weren’t factored into this figure. Despite these numbers, their erasure is ever-present. It is detectable in the now iconic poster created by Shepard Fairey of Munira Ahmed wearing an American flag hijab, which has been seen at every anti-Trump, anti-Islamophobia and pro-migrant protest. Ahmed, who was born in raised in Queens, New York, is of Bangladeshi heritage. But in the poster, her race is unclear, as she has been literally whitewashed: her skin color has been rendered various shades of blue and white. By lightening her skin tone, the resistance literally centered itself around Islam only in its whitest iterations.

Black erasure is further detectable in the onslaught of think pieces on executive order that have rendered non-black experiences the default. Viral videos by progressive news outlets like AJ+ or Vox since the ban have predominantly featured the stories of Syrian, Iraqi and Iranian migrants in their coverage of the travel bans and Islamophobia, but far fewer black people have been featured; celebrities like Moonlight actor Mahershala Ali or Olympic Fencer Ibtihaj Muhammad have gotten press, but their experiences, and those of countless other black civilians affected by the orders, are still often relegated to the margins.

For eight hours on 2 February, many Yemeni-owned bodegas across Brooklyn shuttered in protest of the executive orders. It was heart-warming to see the public support the shopkeepers and the Yemeni community received, and to see members of my own community come together in such a powerful way. But at the end of the day, I was left feeling uneasy: Brooklyn’s sizable Middle Eastern and Muslim community has not mobilized so effectively and visibly for any political cause in recent memory. Despite the fact that many bodegas owned by Middle Eastern migrants are located in predominantly black and Latinx neighborhoods in Brooklyn, and are dependent on their business, they haven’t fought to protect these communities in the same way as they did on 2 February.

I don’t remember a similar mobilization taking place after the police murders of hundreds of unarmed black Americans culminated in massive Black Lives Matter protests these past few years. I don’t remember bodegas taking collective action to protest Stop and Frisk policies that mainly target black New Yorkers. I don’t remember Bay Ridge expressing solidarity with the anti-gentrification movements in Williamsburg, Bushwick or Bed-Stuy. I’m here for my fellow brown Muslims and Middle Eastern folx participating in the struggle against racist policies—I just wish we hadn’t waited until we had been threatened in such an unbearable way. I wish we were vocal for the black community the same way we are for our own, especially when, for some of us, our livelihood depends on them.

I’m aware that as a marginalized group ourselves our ability to advocate for others is limited, but some of us—myself included—can and should do more. We can donate to the Black Alliance for Just Immigration, we can support Black Lives Matter; we can demand that black Muslims and black migrants be centered at protests and organizing meetings related to the executive orders, we can support black Muslims and migrants in the media, and we can intervene when we hear or see members of our community engaging in anti-blackness. If you feel that you don’t have the time, energy or resources to do any of the above, then at least become conscious of the fact that migrant experiences, refugee experiences and Muslim experiences are not exclusively brown, but black, and, sadly, regularly anti-black.

Image via Mel Lou (@melandshark)