‘It wasn’t a place for me to be trans’ – how workplace discrimination against trans people is rife in the UK

Rosel Jackson Stern

09 Oct 2019

Photography courtesy of The Gender Spectrum Collection

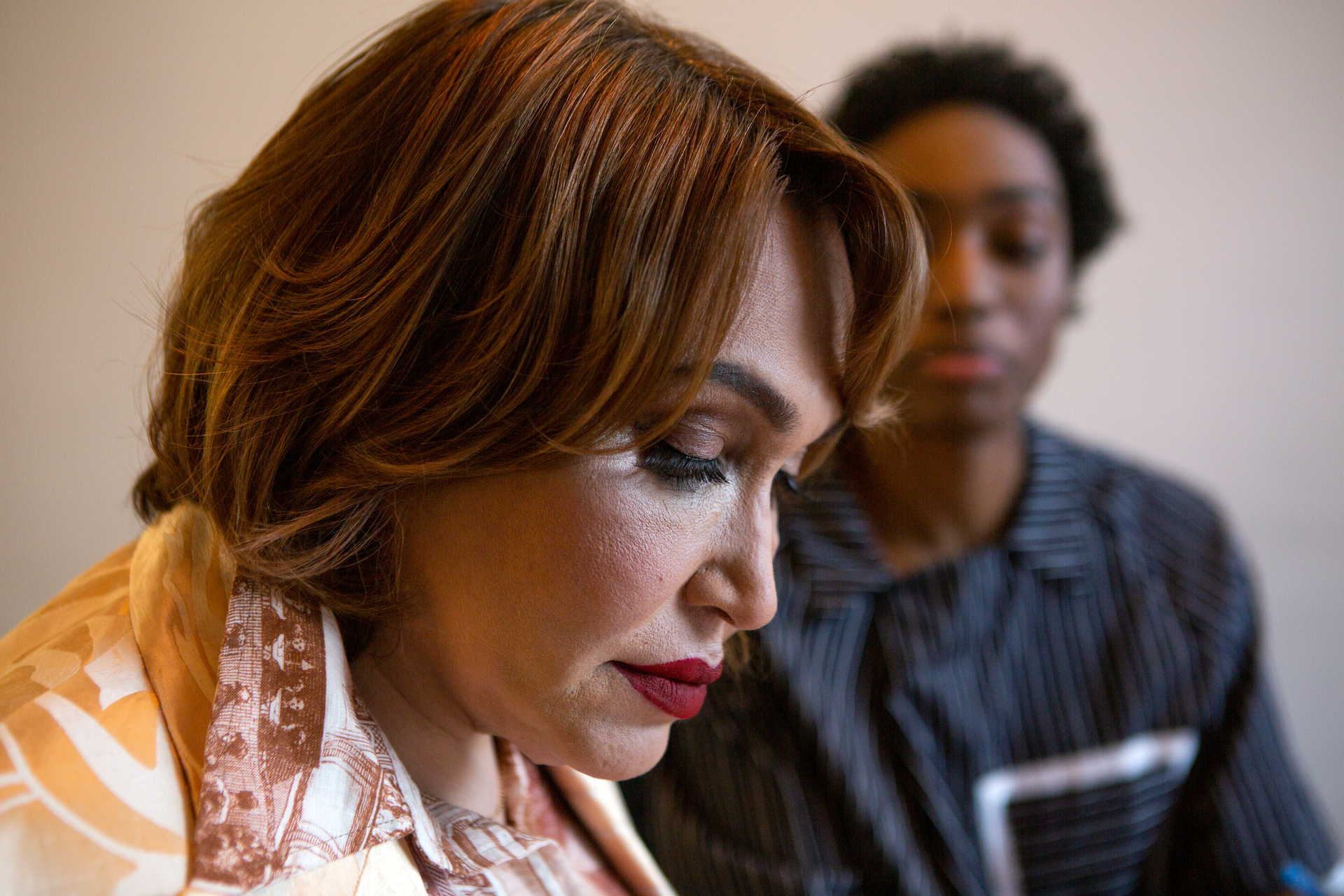

During the making of a big commercial film in the UK, dancer and model Sakeema Crook had an uncomfortable interaction with a member of production. He refused to use her pronouns, saying: “I’m not going to do that because when I look at you, I see a boy”. Sakeema notified two other members of the production staff but nothing ever came of it.

On 8 October, the US Supreme Court began the process of conducting a historic vote on LGBTQ+ rights. The new majority conservative court will eventually decide whether it is legal for employers to fire employees for being gay or transgender in three separate cases, all of which will set an important precedent for gender stereotyping in the workplace. Legal decisions made in the US don’t always affect the UK directly, but their civil rights movement has always had international knock-on effects. So whether you’re cis, trans or non-binary – this vote matters.

“While the UK admittedly offers protection against certain kinds of discrimination, there are no guarantees when it comes to fair treatment.”

Being in the workplace as a trans person in the UK can be stressful. Many of us don’t come out for fear of discrimination, bigotry or the general pressure of doing the emotional labour of explaining our identity to well-meaning cis people. While legislation in the UK admittedly offers protection against certain kinds of discrimination, there are no guarantees when it comes to fair treatment. The Equality Act 2010 protects trans people from direct and indirect discrimination, harassment and victimisation at work by deeming “gender reassignment” as a protected characteristic. However, non-binary identities are currently not legally recognised in the UK under the Gender Recognition Act 2004 and the same act requires trans people to “prove” their identity in a long, inaccessible process. This makes it difficult for trans people to change their stated gender on passports, drivers licenses and birth certificates.

In 2018, Stonewall published a study that found that more than half of the 871 trans and non-binary people surveyed have hidden their identity at work for fear of discrimination. The same report finds that one in eight trans employees (12%) have been physically attacked by a colleague or customer in the last year. Another study found that one in three UK employers won’t even consider hiring a trans person.

Where trans people are tolerated, their acceptance is contingent on how well they “pass” to fit into the gender binary. Cis people’s tendency to understand trans identities only in terms of medical transitions to “male” or “female” puts pressure on gender-nonconforming people in and outside of the workplace. “I immediately knew it wasn’t a place for me to be trans or visibly trans,” says Jei Ganiyeva, a non-binary student in London, describing their experience working at a call centre for an insurance company in Nottingham. “There was another trans man there and he was quite comfortable outing himself as an act of visibility and I really respected him. He was one of the lads, which was very beautiful to see.”

However, Jei paints a picture of workplace culture that had a very binary understanding of gender. They didn’t feel comfortable coming out as non-binary or correcting people on their pronouns: “I was going through a point in my life where I didn’t want to burden any other people.” Jei’s colleagues understood them as a woman and that’s how it continued for the remainder of their time there. “If I had committed to masculinity, maybe it would be different,” they say.

Sakeema also felt the pressure to conform to binary gender stereotypes in the workplace. “It felt like in order to be valid in those peoples eyes and to be respected I had to present really high femme and I had to perform my gender experience and my identity,” she says. After coming out six months ago, she thought her career would be over. She didn’t see many trans people in the contemporary dance world and was surprised when lots of new commercial and editorial opportunities came her way. The increased visibility and representation for trans people in the media during recent years has meant that companies want to feature trans bodies and stories. But Sakeema explains how inclusion, contrasted with blatant transphobia on set, can be distressing and confusing. “I think although the conversation about trans people and trans experience is opening up, a lot of people don’t actually encounter a lot of trans people and don’t know what a trans person looks like and aren’t aware that trans people, non-binary people – whoever – can present in many different ways and still be valid.”

The heightened fetishisation of Sakeema’s body translates into an entitlement to it in the workplace. “There are men who suddenly feel like they have some sort of ownership over my body,” she says. This manifests in an unnecessary “hand on the lower back or touching you as they pass you while the path was very clear and they didn’t need to come anywhere near me to do that.”

This is a powerplay that women, and trans women, in particular, are intimately familiar with: men assuming that your body is up for grabs. While the #MeToo movement has sparked a host of conversations about men’s

“From my conversation with Sakeema, it becomes clear that for trans women, there’s an added layer of entitlement from straight men because they assume that their desire validates your womanhood”

Workplace harassment, as we know, is endemic to structural power dynamics where marginalised genders experience a disproportionate amount of violence. Though not of a sexual nature, in 2016, Alexandra de Souza was sprayed with scent by a coworker who then told her that she smelled “like a men’s toilet”. She was also told that she had a “deep man’s voice” These are only two examples of a long list of abuse Alexandra faced during her time at the discount retailer. Her case was heard by the London Central Tribunal who found her treatment unlawful for which she received compensation. In another case, Katherine O’Donnell sued her former employer at The Times for discrimination, victimisation and unfair dismissal after she was made redundant when the paper closed it’s Scottish edition. The case was closed as the judge found insufficient evidence of the toxic boys club environment Katherine described. While O’Donnell was offered another position at The Times in London, she explained that being a trans woman at the paper “was to experience both systematised sexism and a range of comments and behaviours that were uniquely distressing”.

There are measures that employers can take to better support trans employees that could mean they don’t have to take legal recourse. Trans Engagement Manager at Stonewall, Toryn Glavin, explains that employers can update their HR systems to offer gender-neutral options like Mx, provide gender-neutral facilities, as well as outlining zero-tolerance policies on transphobic bullying, discrimination and harassment. Employers should actively support trans inclusion in workplaces through awareness sessions and training for staff, as well as developing a transitioning at work policy. “They play a huge part in driving progress towards equality. By working together, we can ensure that all LGBT people feel safe and accepted at work, home, and in their everyday life,” says Toryn.

We know that abuse and discrimination thrives on silence and shame, and some workplaces are facilitating more transparency. Alex*, explains that their company has encouraged employees to form clubs around shared interests and identities. This way, their LGBTQ+ forum has been able to lobby management for more support and inclusive language. The process has been slow but “they seem pretty receptive to it, even if they’re kind of surprised sometimes,” Alex says.

They explain that while people who are aware of their pronouns do use them, Alex themselves isn’t super concerned either way. What makes it a safe workplace is that respect is built into the company values and there are many opportunities to give anonymous feedback at all levels of the company. “Sometimes stuff changes, sometimes it doesn’t. But it means that you can at least say something.” Jei similarly points to accountability as being key to negotiating gender in the workplace. “That needs to be a weapon that can be utilised anywhere. I can’t just be like, ‘Don’t misgender me’. There has to be workplace consequences for it.” They explain that this is what gives trans people the power to negotiate their gender in the workplace, to feel like there’s procedure to back them up when cis people are transphobic.

“I can’t just be like, ‘Don’t misgender me’. There has to be workplace consequences for it”

What comes through in all these conversations is that current legislation doesn’t prevent discrimination or encourage employers to support trans workers. The measurers explored in this article depend on employees taking their responsibility to ensure trans workers’ safety, something depressingly few seem willing to do. The eternal precarity of either having to hide our identities or have people openly disrespect them with little to no consequence still remains. People of trans experience know this. Safety often relies on being able to pass in professional settings, but as Sakeema points out: “Gender identity is something internal and that can express itself in any form.”

The visibility and representation of trans people in the media isn’t enough to prevent transphobia or undermine the gender binary. When inclusion and representation is contingent upon gender presentations that are palatable to cis people, the power structures that prop up transphobia remain intact both in and outside the workplace. As we watched the US Supreme Court again vote on the legitimacy of LGBTQI+ rights, the UK clearly isn’t taking the steps necessary to tackle discrimination against trans people in the workplace.

In my conversations with Jei, Sakeema and Alex, their treatment in the workplace is dictated by cis people’s unfamiliarity or disdain for their identities, rather than the legislation that is intended to protect them. Transphobia in these cases, perhaps with the exception of Alex, is given higher priority than their safety and wellbeing. I’m pointing out the obvious here. It’s not news that discrimination of trans people in the workplace thrives because of cis people’s resistance to reckoning with their own gender troubles. You don’t have to when you’re part of the norm. However, it seems important to show that “workers rights”, if that isn’t an oxymoron in a neoliberal capitalist society, have yet to include trans people in meaningful ways.

*Name has been changed

Against the binary: finding home in my intergenerational queer family

Finland has passed life-changing laws for trans people. Why can’t England?

‘The day Ghana’s anti-LGBTQI+ bill is passed, I will be in jail’