All photography by Habibur Rahman

Making waves: meet the Southampton radio station keeping Urdu, Patois and Polish alive for local communities

At a time when local media faces extinction, Unity 101FM has become a vital hub for its diasporic communities. Nimra Shahid reports on the extraordinary story of Unity 101FM.

Nimra Shahid

07 Apr 2020

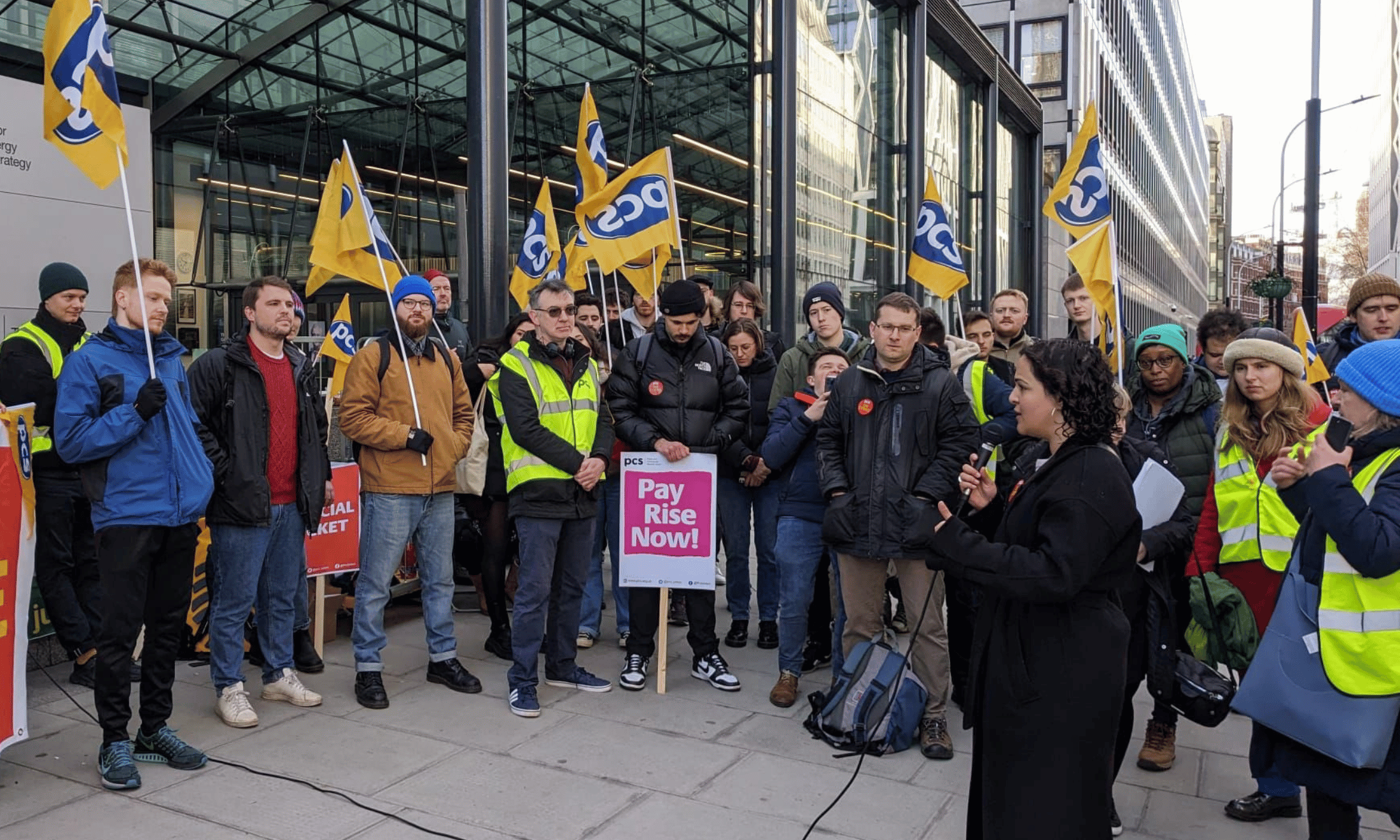

Being sandwiched between a kebab shop and a newsagents is an unlikely place for the heart of local radio news to hide. Yet every Monday evening from 4-6pm, The Drive Time show broadcasts from Southampton Unity 101 Community Radio’s little recording studio, enriching ears across the city with Bollywood beats and updates on everything from the newest restaurant opening, to the latest traffic updates and local competitions for children.

The Drive Time show, hosted by Neha, is one of 42 radio shows broadcast by Unity 101 seven days per week, 24 hours a day, in over 10 languages – including Pashto, Punjabi and Polish – that act as a beacon for Southampton’s diasporic communities. The radio station’s birth in 2003 was an iconic moment. Unity 101 became a localised, reversed version of the BBC World Service that is beloved by both aspiring English speakers looking to strengthen language skills, and migrants far from home who count English as their first language. For Southampton’s multicultural community, Unity 101 provides a much needed link to their cultural heritage and languages. Their slogan says it all: “For the community, to the community, by the community”.

I should know; until I embraced this local news hub, the Urdu language meant nothing more to me than the embarrassment that accompanied me to the school-gates whenever my grandparents came to collect me. While bilingualism has been celebrated by the British Council for “increasing cultural sensitivity”, I saw mine more as only having functional usage, like helping me to translate instructions for my dad during his doctor’s appointments.

And I wasn’t alone. Writing in English in the Indian Diaspora in 2014, Professor Devyani Sharma and Professor Marianne Hundt found that Urdu and Punjabi face declining use in the UK, as they are generally “only used to speak to older relatives who perhaps cannot speak English”, by first and second generation children of migrants, like me.

“After four months at Unity, I noticed changes in my interactions with my heritage. When my grandma’s face would light up at her TV screen as the latest storyline in her Pakistani soap opera unfolded, I revelled in being able to share my opinions on the show with her”

When I turned 19 though, Unity 101 radically changed my relationship with my grandparents’ South Asian tongues. Straight out of college, I had little idea of what I wanted from life until I heard an Unity 101 advert one day in the back of my mum’s car. The multilingual radio was looking to train up presenters for weekly programmes.

Without a second thought, I called Ram. A week later, I arrived at the studio ready to host my first weekly two-hour show in Urdu, while beginning a formal college qualification in community radio broadcasting. Fifteen minutes before my scheduled start, I became anxious. The thought of speaking my broken language on air was terrifying, as I imagined elders listening and laughing at my failed pronunciations. But within minutes of going live, the influx of calls from locals delightedly sharing their day with me encouraged me to keep trying.

After four months at Unity, I noticed changes in my interactions with my heritage. When my grandma’s face would light up at her TV screen as the latest storyline in her Pakistani soap opera unfolded, I revelled in being able to share my opinions on the show with her, her mannerisms revealing how pleased she was. When GEO News relayed updates on diplomatic relations in the subcontinent, I felt privileged at being able to start a conversation with my grandad about one of South East Asia’s most under-taught moments in history – Partition. The station developed my sense of cultural identity. It wasn’t just me benefitting either from the resource; Unity 101 has been vital for Southampton’s increasingly multicultural population.

“There’s nothing like listening to the Geetmala music of the 70s on the radio and hearing apne laug talking about what’s going on in the area around me. It’s as if my friends are keeping me company”

“There were no channels that Asian, black and other ethnic communities could relate to before Unity started, so there was a huge gap that needed filling,” Ram tells me.

He adds that the station has not only had “personal impact” but has become a source of reliable information that helps link the local community and public services, including the police and NHS. Unity 101 is intricately involved in community solidarity too, running events like the annual Hands of Love festival, which celebrates different themes every year, like the contribution of PoC to Britain and NHS.

Unity 101 listener Nusrat Anwar, a 67-year-old who arrived in the UK in the 1960s, shared with me (in Punjabi) how the radio has brought comfort in her later years.

“I spend a lot of time on my own at home now I have a lung condition and my children are all grown up,” she says.

“There’s nothing like listening to the Geetmala music of the 70s on the radio and hearing apne laug (my people) talking about what’s going on in the area around me. It’s as if my friends are keeping me company and I love calling in to request songs.”

In an ideal world, local media outlets like Unity 101 might exist across the country, given 94% of the journalism industry is white. There are initiatives, like London’s Reprezent Radio or Yorkshire’s East Leeds FM. But they’re rare. And rather than receiving an influx of cash to preserve its precious remit, Unity 101 has struggled for funding, relying on a mixture of ad revenue from local businesses alongside various grants for community initiatives.

“For all the 17 years this station has existed, if someone could have paid the rent and bills, I’d be so grateful. We’ve never had core funding and all our presenters are volunteers,” says Ram.

This lack of consistent funding for local media like Unity 101 is endemic. Media giants Global Radio recently planned to close 10 out of 24 radio stations across the country while 245 local news titles closed between 2005 and 2018, reducing further the already low number of outlets that exist for underserved communities to comfortably share their voices. But Unity 101does the most with what it can, including a number of external projects for Southampton locals.

“Unity 101 trainees often possess limited or no educational qualifications but their “graduates” have gone onto enter university, apprenticeships or found themselves recruited by employers across industries including hospitality, beauty and media”

“A lot of our money is allocated to the outreach work which engages the local community,” Ram explains. “That can involve training up young people in colleges in radio production or helping people to gain employability skills”.

Unity 101 trainees often possess limited or no educational qualifications but their “graduates” have gone onto enter university, apprenticeships or found themselves recruited by employers across industries including hospitality, beauty and media.

While the radio has never directly faced xenophobia, station manager Ram tells me that not everyone has been invested in preserving the communities fostered by Unity 101.

In 2014, Love Productions – the team behind Channel 4’s Immigration Street, failed to heed warnings from Southampton’s Derby Road residents, who asked them to steer clear of filming in the local St. Mary’s area surrounding Unity 101. After the broadcast of Benefits Street in early 2014, the St. Mary’s community feared they would be fractured and misrepresented.

“Unity 101 consequently mobilised locals, who made their sentiments about the programme clear, resulting in the Immigration Street being cut from six episodes to one”

Their concerns weren’t unfounded after one local remarked that there was going to be a lot of “backlash” from the “anti-Muslim” stance. Hampshire constabulary stepped up patrols in the area, with the aim of keeping residents safe.

Unity 101 consequently mobilised locals, who made their sentiments about the programme clear, resulting in the Immigration Street being cut from six episodes to one. The success of that campaign has seen Unity 101 continue to build ties with Derby Road’s community. In 2016, Ram launched the annual Derby Run; a free family event encouraging Southampton people to “boost their health” while enjoying food and activities. It’s been a community favourite ever since.

The principles the station runs on, like integrity and maintaining trust with the city’s diasporic communities, are well understood by Veronica Gordon, who has nurtured relationships with Southampton’s black community for over 10 years as part of her regular Unity 101 show, Vibrant Vibes. The weekly programme covers news and music in the studio, with a focus on African and Caribbean cultures.

As a child of the Windrush generation, Veronica tells me that one of her favourite moments has been producing a series of shows in October 2019, where she and her fellow presenters invited black Caribbean elders who came over to Southampton in the 1950s and 60s. “One moment that touched me most was when the chair of the Black Heritage Association revealed a beautiful part of her story when she came over,” Veronica says. “It’s lovely that people share the things that matter most to them”.

“The demand for more black narratives has led Veronica to train up “roving reporters”, using her experience from years working as a journalist at ITV News”

Sharing the joys and stories of black communities across the South East region has been fundamental to the success of Vibrant Vibes, which has a thriving and loyal listenership who regularly interact with the show via sending in news or their experiences. “I loved covering a local Nigerian man’s success in writing a semi-autobiographical play, which sold out at Southampton’s Nuffield Theatre,” recalls Veronica.

“He wasn’t a playwright by profession but his story of being adopted by a white British family after being born here in 1965 was incredible.

“I hope his experiences will inspire others to think that if he can go for his dreams, they can too.”

Vibrant Vibes amplifies the stories of the black community in Southampton

As the audience of Vibrant Vibes has grown, so has the pool of fresh talent eager to keep Unity 101’s unique form of broadcast journalism alive. The demand for more black narratives has led Veronica to train up “roving reporters”, using her experience from years working as a journalist at ITV News. Her team have covered stories on topics including youth loneliness and produced features on looking after black hair – one of their most popular series to date.

Having seen presenters at Unity 101 go onto jobs at BBC Radio London, ITV and other newsrooms, Veronica notes that the radio has been “integral” creating a pipeline of regional talent for the media. While not every volunteer at Unity 101 aspires to become a journalist, the skills they gain are invaluable in enabling them to be active in their community and give them confidence in amplifying their voices.

Veronica talks of a recent story she worked on, which aimed to raise awareness and challenge preconceptions regarding the struggles that mixed race children face in the process of adoption. Witnessing the effect of sharing stories like these on a platform like Unity 101 has now inspired her to start her own media company, Our Version Media, which will report on positive stories from black communities.

As journalism yearns for new voices amidst the homogeneous coverage of issues like Brexit, the need to protect and support outlets like Unity 101 has never been more pressing.

In championing the heritage of multicultural South East England’s languages, while creating a space for other diverse communities to have their voices heard, the radio plays a crucial role in bringing people together at a time when society is polarised by differences. As Arundhathi Roy said: “There’s no such thing as the voiceless, only the deliberately silenced and the preferably unheard”. These are the voices that Unity 101 wants us to hear and there’s never been a more important time to tune in.

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?