‘Bona, Charlottesville’, Courtesy of the Zanele Muholi and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

How four women and non-binary people of colour used self-portraits as a vehicle for rebellion

From Ana Mendieta’s gender-bending performance pieces to Adrian Piper’s racially provocative paintings, the art of self-portraiture has long been used to defy societal norms.

Precious Adesina

10 Jun 2020

TW: sexual assault

While self-portraiture isn’t exclusive to people of colour – or even inherently political – it comes as no surprise that artists from minority backgrounds have yielded the power of turning their gaze on themselves. In a world where many women and non-binary people of colour often feel scrutinised and subjugated, this medium has been used as a means of gaining a sense of autonomy and to challenge the preconceived notions that people have of the marginalised groups they belong to.

If you ask someone to name a woman of colour whose work centred her own image, Mexican painter Frida Kahlo usually springs to mind. However, there are so many more women and non-binary people who operate both in front of and behind the lens as a way to explore questions around gender, beauty, class and race. Here, we journey through four trailblazers’ work to see how taking pictures of yourself can be a riotous political tool.

Carrie Mae Weems

In 1989, a black photographer in Northampton, Massachusetts flipped the focus of her camera from others to herself. She dedicated a portion of each day to photographing herself at her kitchen table until the following year, sometimes alone, sometimes nude, and sometimes accompanied by family and friends. A collection of these images would be used to tell a story that would not only be important to her, but would continue to hold cultural significance decades later and inspire more female artists to use self-portraiture in their own work.

Those photographs would become Carrie Mae Weems’ Kitchen Table Series, in which she challenges gender norms by placing herself in a space that is often associated with women. This series would have been the first time a lot of contemporary artists of the time saw an African American woman reflecting on her own life in her art, inspiring them to do the same. Thirty years on, it still feels just as poignant today, especially with the black experience being at the forefront of global conversation, and many trying to ensure that black women remain a part of the discussion. In a number of these images, you see yourself or someone you know as her or the satellite figures around her.

She understood the versatility the medium could provide. In an interview for Art 21, Carrie Mae says: “It just sort of swung open this door of possibility, of what I could actually do in my own environment, whenever I chose, and whichever way I wanted.”

Adrian Piper

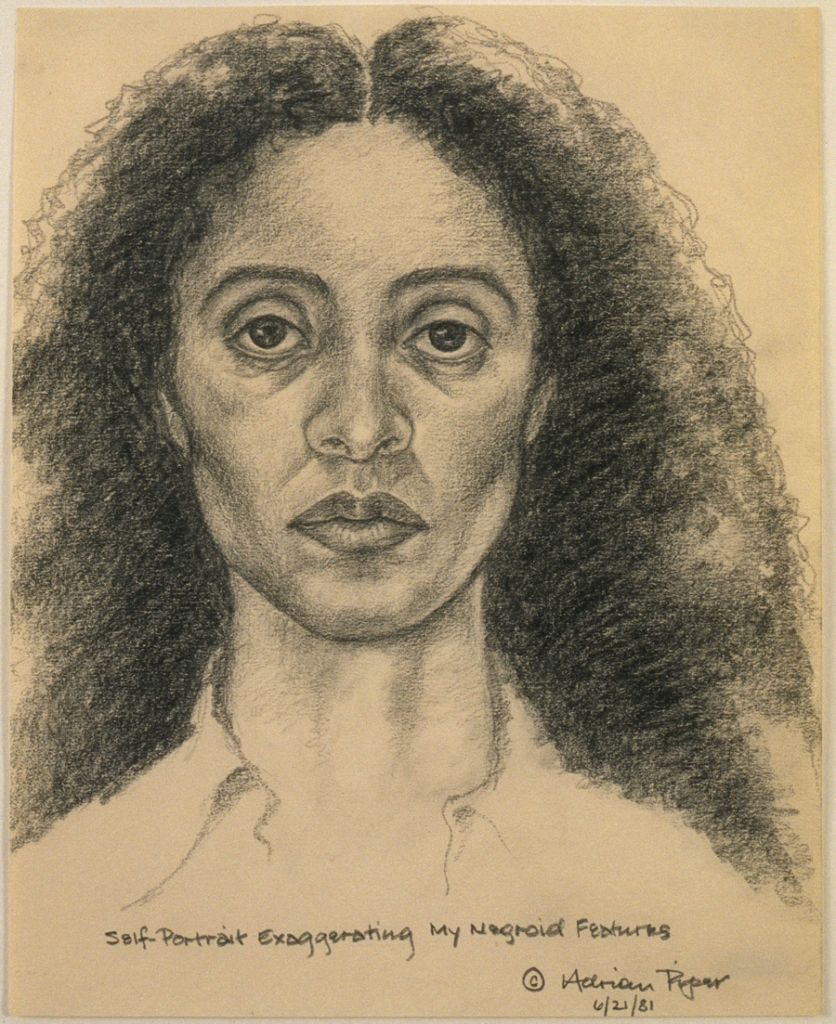

Just as Carrie Mae documented life by using herself as a surrogate for other people’s experiences, Adrian Piper used her own image to question society, often drawing on her mixed heritage to provoke discourse surrounding race. In ‘Self-Portrait as a Nice White Lady’, a photograph of Adrian altered with oil crayon made in the mid-1990s, the background of the image is a striking red and “WHUT CHOO LOOKIN AT, MOFO” is written in a thought bubble over her head. At first glance, with her straight hair and light skin, she appears white, but the aggressive colour and angry thoughts seemingly force the viewer to question her perceived race and, in turn, address their own prejudices about how they deem certain groups of people to behave. “The altercation asks viewers, ‘Is this how you see me once you know that I’m black?’” writes art historian John P. Bowles in Adrian Piper: Race, Gender, and Embodiment.

Adrian bolsters this narrative in ‘Self-Portrait Exaggerating My Negroid Features’, a drawing that over-emphasises her “black facial features” first presented in the New Museum catalogue for its exhibition Events: Artists Invite Artists in 1981. In a statement for the show, Adrian addresses the ways beyond her drawing that people identify her as black. “I dance ‘black’,” she wrote humorously, explaining that while at an event with her white friends, a black man whispered to her, “You can’t be white and dance like that.”

She also notes that, in art school, she was told by the artist Rosemary Mayer that her art history teacher had asked whether Adrian was black, the marker being that “she is aggressive”. By conflating these starkly contrasting attributes, one debatable in whether it’s complimentary and the other undoubtedly not, Adrian highlights how both endorse the damaging idea of typical behavioural traits in black people. These are the sort of comments that growing up make us overly conscious as a black woman, afraid to behave both too black but also not black enough. Though the fact people are questioning her race in the first place suggests she also benefits from the privilege of being white passing.

Aside from her unique art Adrian is a very complex character. In 1987, Adrian famously penned an open letter to the art critic Donald Kuspit who published an essay on her work, accompanying the letter with an unflattering drawing of Donald as a cockroach she was exterminating. In an odd turn of events, Adrian took it upon herself to “retire from being black” in 2012 at the age of 64. This was achieved by posting an image of herself on her website where her skin was digitally distorted to look artificially darker. “I have decided to change my racial and nationality designation. Henceforth, my racial designation will be neither black nor white, but rather 6.25% grey,” she wrote. “Please join me in celebrating this exciting new adventure in pointless administrative precision and futile institutional control!”

Like much of her work, it showed her disheartment in the difficulty of trying to meet other people’s expectations when their perceptions are clouded by prejudice. Still, unlike Adrian, who is racially ambiguous, being able to shelve one’s blackness is a luxury not many black people have.

Zanele Muholi

The use of post-production to darken one’sskin in an overt manner by people of colour isn’t exclusive to Adrian and is similarly used in the work of non-binary South African artist Zanele Muholi, whose art challenges notions surrounding beauty, feminism and the LGBTQI+ community. In the photo series Somnyama Ngonyama (meaning “hail the dark lioness” in Zulu), Zanele dresses in different outfits to portray different personas and manipulates the photos to alter their skin. Art historian Tamar Garb says that, by doing this, “Zanele denaturalised all the conventions and tropes that they play with. They take up some of the conventional ways that black women’s bodies are seen and undermines them through parody and humour.”

An example of this is the photograph ‘Ntozakhe II’, in which they satirise the Statue Of Liberty. “Zanele uses scouring pads on their head [in place of the crown] to reference work and domestic labour,” Tamar explains. Consequently, the piece becomes about subservience and lack of freedom, in contrast to what the Statue Of Liberty itself is meant to represent.

Before turning to self-portraiture, Zanele spent a decade on Faces and Phases, a series they began as a reaction to the increasing homophobic hate crimes and murders in their country. They wanted to shed light on the black, gay communities in South Africa. In the collection of over 250 portraits, Zanele’s subjects, transgender men and lesbians, stare into the camera with a tranquil gaze that suggests they are ready to share their story, whether that be of happiness or sorrow. Their work would go on to be considered as much activism as it is art, and later the photographer would record people’s stories of rape, assault, harrassment and abduction.

However, Zanele eventually became worn out by the heartbreaking stories of abuse they were told – which is why they turned their gaze on themself. They hoped not only to use self-portraiture as a means of therapy, but also to force themself to look inwards. ‘‘[Photographers] get caught up in other people’s worlds, and you never ask yourself how you became,” they told The New York Times in 2015. By creating self-portraits, they were able to explore their own personal relationship with gender, sexuality and race, and the ways in which these identities interconnect. While the experiences Zanele addresses in their work aren’t easy ones, and the imagery they provide is staggering, it also makes the stories and messages easier to absorb.

A solo exhibit of their works will be exhibited at the Tate until late 2020.

Ana Mendieta

Difficult topics require artwork that is also difficult to digest, and some women have used the medium in a disruptive way to lay bare the taboo topics they’re discouraged from talking about openly. For example, a recurring element in Cuban-American artist Ana Mendieta’ work is blood, which is often used to shed light on topics of domestic violence and rape, and challenge the treatment of women in society. These works are uncomfortable to look at as you feel like a bystander in the suffering of another person and in turn makes you wonder whether you’ve done all you can to reduce such pain in the real world.

In 1973, after hearing about a rape and murder on campus while studying at University of Iowa, Ana invited her colleagues to her apartment to view her performance, ‘Untitled (Rape Scene)’. When they arrived they found her naked from the waist down, tied to a table with her face and body covered in blood. A gory sight. This would remain one of her most controversial works of art throughout her career. Strangely the gendered violence she’d shed light on in her work foreshadowed her own demise as she fell 34 floors from the window of her New York apartment in 1985, fans of her work suspected foul play from Carl Andre her former partner who was there at the time.

As a performance artist, much of Ana’s art comes in two forms: the ephemeral acted-out piece, and the everlasting documentation of it to relay the unpleasant message to others. ne of her most famous artworks is ‘Untitled (Facial Hair Transplants)’, made in 1972 for her MA – a piece so blatant in the way it questions typical attributes associated with men and women that it’s still often used in exhibitions as an example of how to open up questions around gender. In this series of photos, the artist glues facial hair donated from a friend to her face. The photos document the entire process, from it being removed from his face to the final product on hers. “After looking at myself in a mirror, the beard became real,” she wrote of the act in her thesis. “It did not look like a disguise. It became a part of myself and not at all unnatural to my appearance.”

The use of a beard in her work illuminates the significance society puts on parts of the body to determine gender and beauty – especially when she is contrasted with her friend, who is of a different race (white) and sex (male). The same beard on a man and on a woman hold different values much like other parts of the male and female bodies do due to societal constructs. “I like the idea of transferring hair from one person to another because I think it gives me that person’s strength,” she explains. That transferring of “strength” in ‘Untitled (Facial Hair Transplant) is the shifting of male power and the movement away from a patriarchal society.

Me, Myself and I is a week-long celebration of self portrait photography focusing on the power of creating art alone.