Courtesy of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye paints whatever she damn well wants

Ahead of her Tate Britain opening, the acclaimed artist speaks exclusively about unleashing the power of imagination, leaving space for fantasy and the freedom to paint black people just because.

Precious Adesina

02 Dec 2020

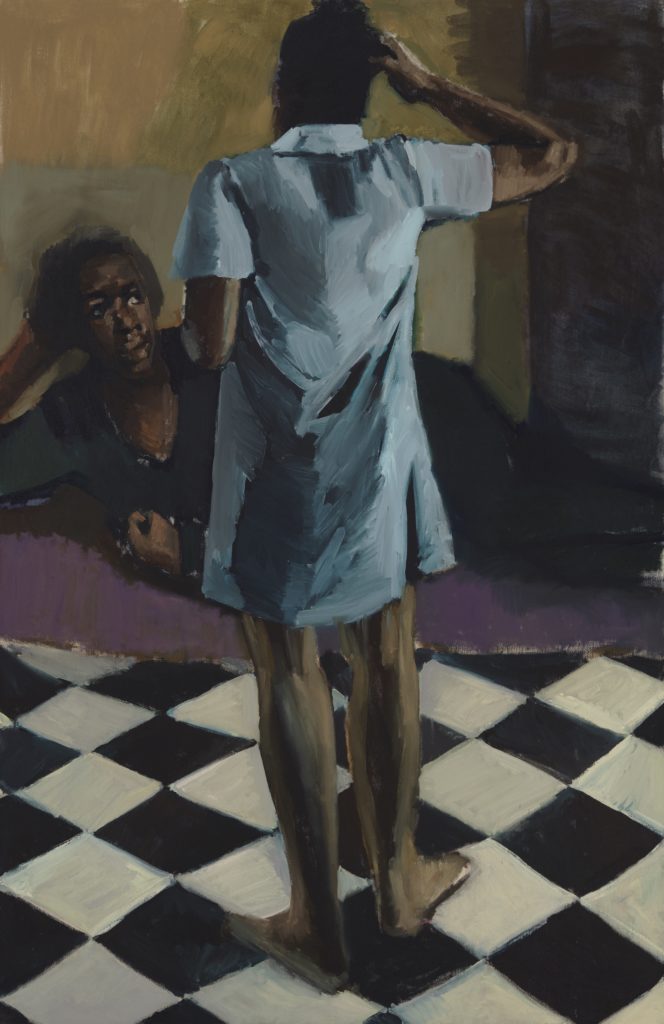

A shirtless boy wearing only long black shorts looks into the distance at a landscape shrouded in uncertainty. The colour palette of the painting of him is so monochromatic that his skin, the abyss he looks into, and the rocks he sits on vary only in slight tone. His slouch, his solemn expression, the way he rests his arm on his bent leg, with each quick thick lick of paint, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye builds an exciting hyperreal scene. It is hard to believe that the boy does not exist.

Like many of the subjects in paintings by Lynette, he’s a figment of the artist’s imagination. “The reason I didn’t want to work from life was because I wanted that open-ended freedom to do whatever I wanted with them,” she says over Zoom while sitting in her studio as the terrible connection on my part noticeably cuts in and out. “As soon as I related them to people who existed, then it felt like the person I was painting had to be honoured, whereas working the way I do, there can be flushes of fantasy.”

This painting titled The Counter (2010) by Lynette is one of 70 paintings that will be showing at her most extensive retrospective to date at the Tate Britain titled Lynette Yiadom-Boakye: Fly In League With The Night. Starting from 2003, the exhibition will work its way through her art over the last two decades, which has seen her gain international recognition and become one of the most celebrated painters of her generation. In 2019, her painting Leave A Brick Under The Maple (2015), a life-sized portrait of a standing man in hues of burnt-orange sold for almost 1 million dollars at an auction at Phillips.

But that is just one of her many achievements. Lynette’s exhibition at Chisenhale Gallery in 2012 showed what was a new body of oil paintings at the time and led to her being nominated for a Turner Prize the following year. In 2015 she had another solo exhibition at The Serpentine titled Lynette Yiadom-Boakye: Verses After Dusk. And, a little more recently, her work was explored again at the New Museum of Contemporary Art in New York in 2017 and a year later she won the Carnegie Prize.

Despite this, Lynette says she isn’t a natural colourist. “The more I work, the more I come to gain an understanding of colour. You learn it as a child and then you get distracted by a whole bunch of stuff. Then you come back to it and realise that there’s a whole process before you can fully understand how to work with it.”

“As soon as I related them to people who existed, then it felt like the person I was painting had to be honoured, whereas working the way I do, there can be flushes of fantasy.”

But, what the painting also exemplifies is the timelessness that is present throughout her oeuvre. Any clothes, landmarks, architecture, technology that could be attached to a specific point in time has been stripped of her work. “I want the subjects of the paintings to have the same freedom that I feel,” Lynette says. “I want that sense of feeling transported.”

She laughs and looks around at her latest paintings on linen which she says will now feature in the exhibition that has been severely postponed because of the pandemic. “This is going to sound mad, but when I’m painting there’s a sort of transcendence. As a painter, there’s things that you’re doing that are inexplicable. Not without logic, but you can get carried away. The painting starts to tell you what it needs.”

It’s clear she has confidence in what she does, the type that comes with years of practice (and praise), but unlike many people held to the same regard, she is humble about it. When she does speak of herself, it’s about how she’s still learning or “just getting to understand painting more” despite the fact it is something she has clearly mastered.

But rather than denoting a lack of confidence it’s actually Lynette learning to feel free enough to not have to justify every minute detail. (which is pertinent since I’ve been asking her about the smallest details of her process). “In art school for example, you always have to explain what you’re doing, but you get to a point later in life where you suddenly realise that you don’t have to,” adding that even her titles are not designed to try and clarify anything for the viewer. “I know what the connection between the title and the painting is for me and many people who encounter it will understand what the connection is. But, it doesn’t matter if they don’t. I’m not interested in that.”

She notes that one way people seem to unduly define her work is by the skin colour of her protagonists who are almost always black. Many articles try to lay out some deep importance on this choice, but it never seems to be coming from her directly. “I’ve never defined the work like that myself or even questioned it,” she agrees. “It has always been something that people feel they have to mention which I’ve found weird. It’s asking the wrong question. It shouldn’t be ‘why is everyone black?’ but ‘why shouldn’t everyone be black?”

“People co-opt their own bizarre ideology onto what you’re doing and when it’s just not what you’re thinking, that’s what’s galling.”

Black creatives often have political ideas superimposed on their work, especially in a year awash with racial unrest. “I think we’re all getting it at the moment. People co-opting their own bizarre ideology onto what you’re doing. It’s a lot of the wrong people too,” she says “And when it’s just not what you’re thinking, that’s what’s galling.”

What has inspired her is reading. “I’ve always been a big reader of fiction,” she explains. “I’d become obsessed with picturing people, things, objects or places in my head as they are described to me.” One of her favourite novels is Giovanni’s Room by James Baldwin, a 1956 novel about an American man living in Paris and the tumultuous relationship he has with other men. “I always found that absolutely extraordinary, how someone can write a character that is far from their own experience,” she says. It sharpens her own imagination.

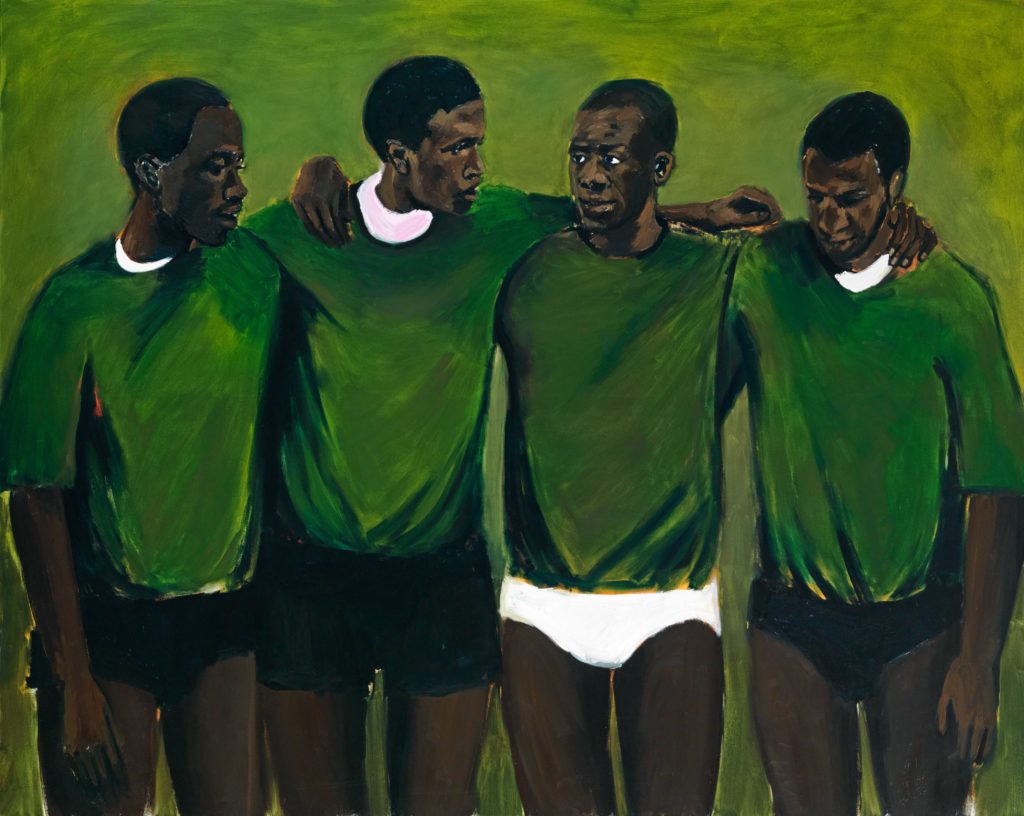

Citrine by the Ounce (2014)

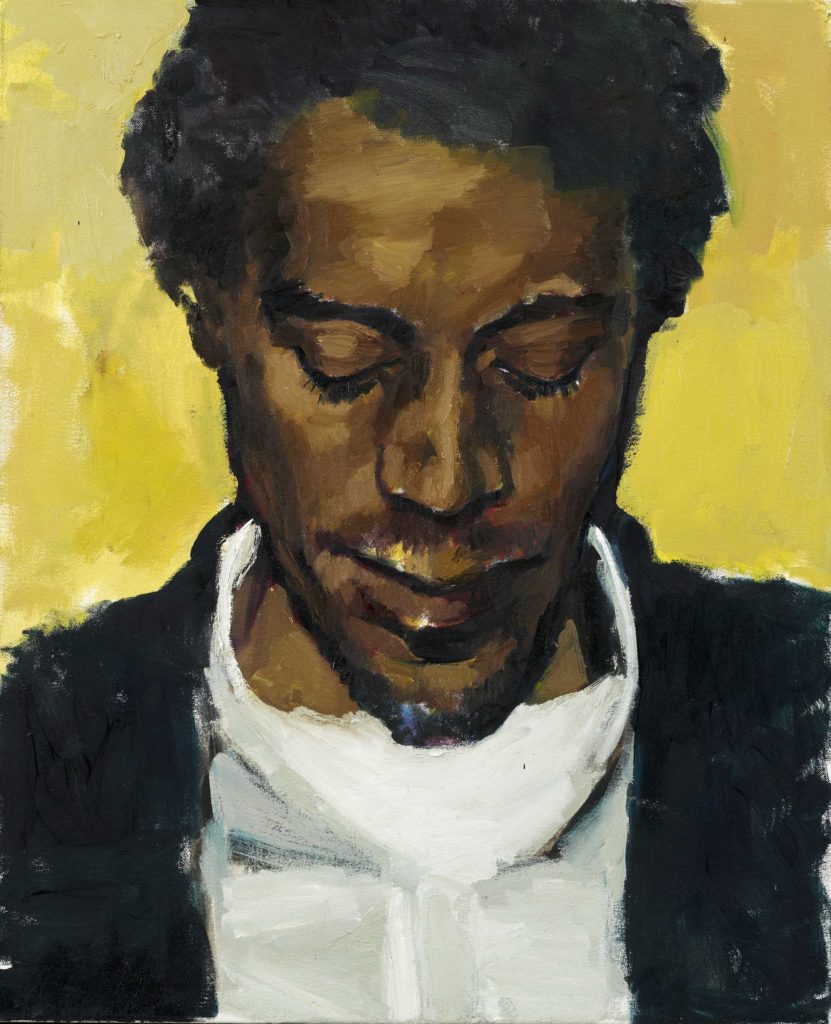

To Improvise a Mountain (2018)

While Lynette had been known for working very quickly, initially completing entire canvas paintings in a day, but with a lot of her work over the past few years being on linen she has been forced to slow down. . “I like being able to take a bit longer and also go back and completely rework something and have it still make sense,” she says. 2020 has decelerated a lot of people’s daily life. “You have this real sad realisation that your actual life isn’t much different to being under quarantine. The only thing that was different was that I couldn’t see people as much. Everyone else is calling you up going crazy, and you’re like ‘what’s the problem.’”

As a painter, Lynette is fine spending days on her own. Instead, the exhaustion comes from working at home. “I didn’t come to the studio for a while, I just worked in a small space in the back of my house.” This forced her to work on a smaller scale, which left her feeling less worn out than usual. “When I was working at home I was getting to the end of the and I just wouldn’t be tired. It made me realise how physically demanding it is to work on something big. So I started doing home workouts to get rid of some of that extra energy I had. It’s difficult to find creative ways of doing that.”

While we’re talking my internet cuts out just before we’re able to say goodbye. And I find myself laughing at the irony of our isolation chat. We spent a good chunk of our conversation talking about how the pandemic hasn’t affected her much but if this was pre-Covid, we’d have met in person over a coffee and we wouldn’t have had to pause our chat so many times because my Wi-Fi connection was unexpectedly down that day and maybe we’d have had a proper farewell. But, I also love that our chat ended with the same level of mystery as her paintings.

See Lynette Yiadom-Boakye: Fly in League With the Night at Tate Britain, London, 2 December until 9 May.