10 years since Tunisia’s revolution and promises of freedom are faltering. But what comes next?

A decade has passed since the Tunisian revolution. As the president takes power in a coup d'etat, is there still a future for the democracy that was pledged?

Myriam Amri

06 Aug 2021

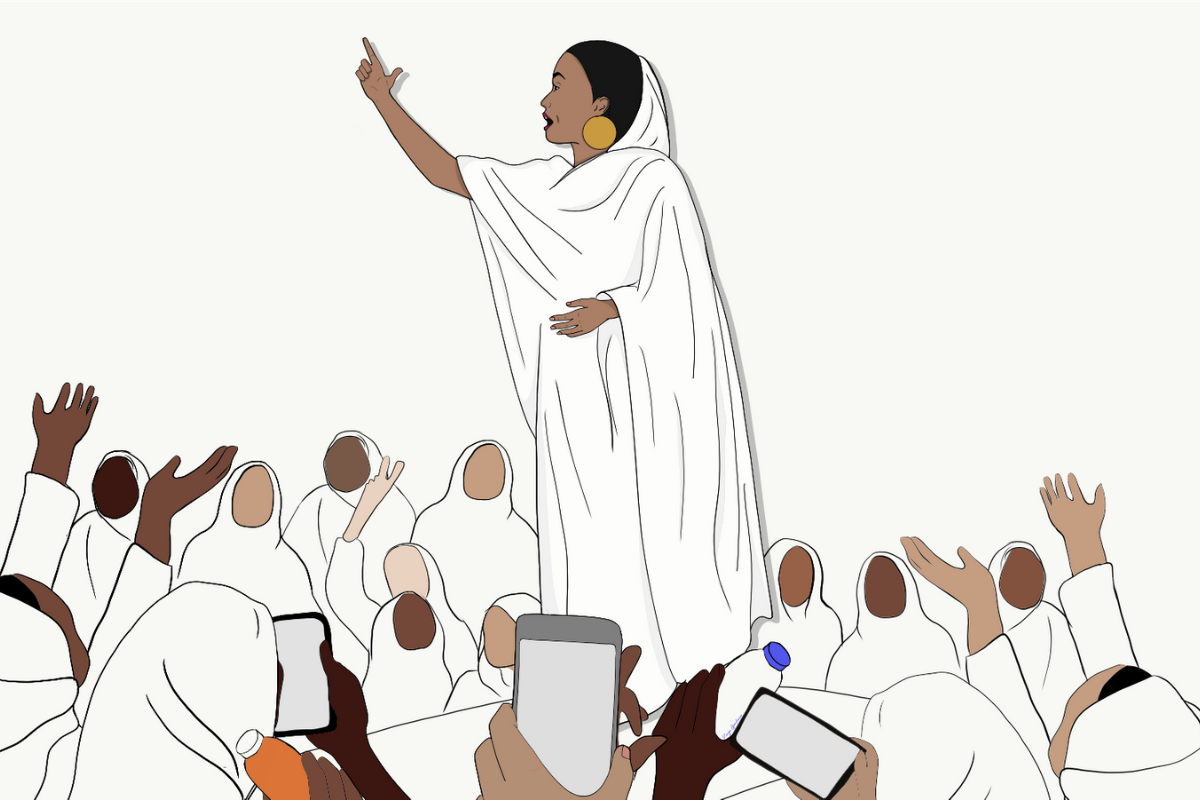

Amine Ghrabi/Flickr

In Tunisia, 25 July has always been a notable day. It’s a national holiday commemorating “Republic Day”, the date a new regime was established in 1957, after Tunisia’s independence from French rule. In the past decade, 25 July had also become a significant day for Tunisian politics.

Notwithstanding the annual protests that occur on that day since the 2011 revolution (the uprising that kicked off the infamous ‘Arab Spring’), it was on 25 July 2013 that leftist leader Mohamed Brahmi was assassinated outside his home. Six years later, it was on another 25 July that president Beji Caid Essesbsi passed away unexpectedly, throwing the country into constitutional uncertainty. And this year, 25 July also lived up to its promise of abrupt change.

That evening, after a day of protests across the country against the current regime, Tunisian president, Kais Said announced on 25 July that he was invoking Article 80 of the 2014 Constitution, which allows the president a state of emergency following an “imminent threat”. He declared that following the article, he was freezing parliamentary activity and recalling deputies’ immunity, sacking the prime minister, and declaring himself prosecutor general, all while being backed by police and military forces. In other words, Kais Saied declared a coup d’état.

In the media and across digital platforms, reactions were mixed as people pointed out Article 80 that Saied used to justify his coup, noting how his decisions were unconstitutional. Yet many in Tunisia rejoiced at the news as people across neighbourhoods flooded the streets way past the curfew imposed due to the pandemic.

The euphoria on the streets came from months, if not years, of economic, political, and social woes that have plagued Tunisia’s post-revolutionary experiment. When the protests of 2011 began, the demands were for social and economic justice, for a future of “karama” (dignity) for Tunisians. Yet over the past decade, an entrenched economic crisis has been the only unwavering certainty on the horizon. Most of the economic elites responsible for the corruption of the dictatorship era were amnestied.

Unemployment levels grew as people attempted to scrape by outside formal employment, with unemployed graduates turning to work as street vendors to make ends meet. Tunisia became divided between those who had access to state jobs or positions in the private sector and those who had to operate outside contracts and legal frameworks and scrape by. In reality though, the rise of prices meant that most people, even the once-envied state employees, became increasingly precarious after the revolution.

The structure of the economic system itself, an economy of indebtedness and crony capitalism, where certain influential families and individuals hold entire sectors of the national economy, should have been radically transformed. Instead, only make-shift solutions were implemented. At the same time, international pressure for neoliberal reforms grew as the IMF attempted to unsuccessfully implement programs of privatisation in the public sector in exchange for loans, while the European Union launched an entire campaign for a free-trade agreement that would destroy Tunisia’s fragile economy and was met by protests on the streets.

In the past decade there have been attempts at radical re-imaginings of the Tunisian economy, such as worker-owned-factories or the reclaiming of indigenous lands in the South. But these attempts have been stalled and sabotaged by a system held in the hands of people who benefit from the status quo. The Covid-19 pandemic also could not have come at a worse time for the Tunisian economy, which is heavily reliant on the exports of primary goods, textiles, and tourism – all industries that have significantly shrunk in the past year.

“The so-called ‘democratic transition’ privileged a liberal response that equates ‘voting’ with ‘freedom’ and derailed what should have been a path towards social justice”

When the pandemic hit, the government announced relief stipends. Yet almost 40% of the labour force, either those on short-term contracts or whose work was not formalised, fell into the crevices of the system and could not access the meager 200 dinars (£50) promised. The exported textiles industry, for example, employs women on very low wages and who are often the only breadwinners in their household. These factories often have different contract systems that allow them to hire employees short-term and without paying benefits.

When Covid-19 hit last spring, factories closed and many of these women found themselves without salaries and unable to qualify for the relief stipend. For many Tunisians, these stories of growing precarity have marked the past decade, away from the shining mirage of a democratic transition that has never even tried to alleviate their hardships.

The political system became, in some ways, the echo chamber of this unchanging system. The so-called ‘democratic transition’ has never been a satisfying model for the radical transformation that the Tunisian revolutionary moment carried. It privileged a liberal response that equates ‘voting’ with ‘freedom’ and derailed what should have been a path towards social justice. In the past year, the parliament had turned into what Tunisian Twitter calls “#TnZoo”, as scenes of everyday disputes, blockades, and fights between deputies filled the difficulties of the everyday. The Islamist party Ennahdha, whose leader Rached Ghannouchi was the head of the parliament until July, is the largest party in Tunisia’s parliament and has been central to stalling political processes. Its refusal to appoint judges to the Constitutional Court rendered it increasingly unpopular in the eyes of Tunisians across political lines.

The parliament, supposedly the strongest institution in Tunisia’s post-revolutionary constitution, has itself been accused of plundering the country’s resources and labor. Since the last elections of 2019, many stories of corruption have emerged, from cases of candidates being financed by foreign entities to deputies using their political immunity and leverage to access private contracts. On the streets, young people, mainly from working-class neighbourhoods have been forced to battle a police state, as – despite the supposed transition to ‘democracy’ – police officers have never ceased arbitrarily arresting, brutalising and murdering people. In the past year, protests against police brutality and the police state, a legacy of the dictatorship, have become at the forefront of grievances in the streets.

Yet, today the coup throws everything back into uncertainty. While the situation remains open to all sorts of speculation, the coup brings the country into a bigger political crisis than ever before. It is a dangerous precedent for any political leader to concentrate power in an unprecedented way. It also creates a political deadlock that derails from structural conversations on the economy or the police state and puts back the fight for “democracy” before the fight for social justice.

Kais Saied promised to address people’s grievances within 30 days, an almost impossible task in a country that requires a radical reordering of political and economic structures. Yet Tunisians are exhausted from the past year where they had to navigate economic dispossession, grief for the many lives lost in the waves of Covid-19, and countless protests met with increasing state violence. While their immediate future is unclear, it seems that once more Tunisians may be forced onto the streets to fight for freedoms that have been demanding since the false promise of ‘democracy’ was first dangled before them, 10 years ago.