Marius Arnesen via Flickr

Why feminist solidarity with Afghanistan is about more than women and girls

Afghan women and girls are undoubtedly imperilled by the Taliban takeover. But hyperfocus on their vulnerability risks repeating mistakes of the past.

Leila Sackur

25 Aug 2021

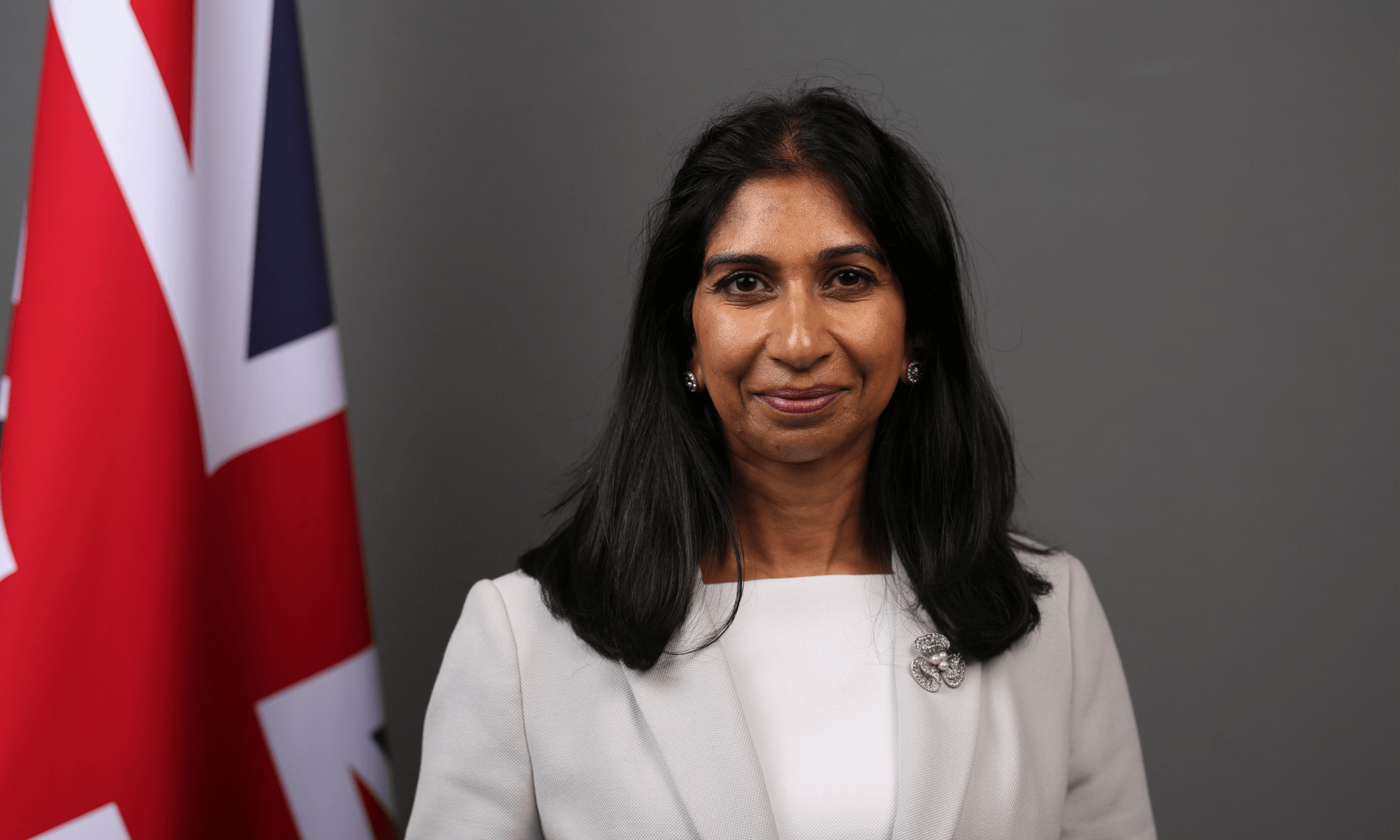

On 18 August, the UK Home Office announced their pitiful new plan to bring refugees from Afghanistan to safety. Over the next five years, the British government will supposedly take in 20,000 Afghan people, prioritising women, children and religious minorities for asylum, who are deemed most at risk from the violence of the Taliban. In the UK, much of the media coverage of the plight of women in Afghanistan has heavily featured discourse around the Taliban’s enforcement of the burqa. On Twitter, a black-and-white image of women in Kabul in miniskirts has been circulating, presenting a linear, and false, narrative of descent from the modernity of the 1970s to the barbarism of today. It’s the same photo that ex-President Trump’s National Security Advisor H. R.McMaster showed Trump in 2017, to persuade him to extend the then-16-year-long occupation.

There is clearly no doubt that women are under particular threat from the Taliban. In their six-year rule from 1996 to 2001, they banned girls from attending schools, women from working, and instituted harsh and public corporal punishments and executions for crimes of adultery and indecency. In recent months, according to the Associated Press, in Taliban strongholds in northern Afghanistan, women have been told not to come into work and university, schools have been set on fire, and many who have held public office have been assassinated, despite ongoing claims from the group’s new PR machine that their new attitude to gender is liberal and moderate.

“Yet the hyperfocus on Afghan women and children without a contextual understanding of Afghanistan’s modern history or Western imperialism is not the feminist take some may think it is, and may pave way to even more violence”

Yet the hyperfocus on Afghan women and children without a contextual understanding of Afghanistan’s modern history or Western imperialism is not the feminist take some may think it is, and may pave way to even more violence. In the 1990s and 2000s, the plight of Afghan women was used by many on the right in the US and the UK to justify the invasion of Afghanistan. In a November 2001 address, then-First Lady Laura Bush claimed that “the fight against terrorism is a fight for the dignity and soul of women,” a statement that was echoed by her British counterpart Cherie Blair. Carolyn Maloney, a New York congresswoman, wore a burqa on the floor of the House of Representatives, decrying how claustrophobic the religious garment was, and a 2002 issue of Ms. Magazine called the US-UK invasion of Afghanistan a ‘coalition of hope.’ According to WikiLeaks, in the Obama years, the CIA hoped that Afghan women could serve as “ideal messengers in humanizing the ISAF [International Security Assistance Force] role against the Taliban,” turning their struggles into PR to garner support from Europeans for the ongoing war.

In her seminal 1985 essay, ‘Can the Subaltern Speak?’ Gayatri Spivak described the justification of civilising colonial missions as “white men saving brown women from brown men.” The invocation of the agentless vulnerability of women and children has been used by colonising powers to justify invasion a thousand times over: from the British in Palestine to the French in Algeria. Not only does this heightened focus on women dehumanise through homogenisation, but it also constructs brown men as inherently violent and boys potentially so, barring them from the status of ‘civilian’. Because to the white gaze, Afghan boys and men are indistinguishable from militants, or might later become them – their murder is justified and claims for asylum constantly questioned. Moreover, the Western repression of the burqa since the beginning of the War on Terror has actually increased Islamophobic attacks against Muslim women in Europe, because those who choose to wear head coverings are easily identifiable as Muslim.

“Our response to the gendered violence of the Taliban cannot be an endorsement of more military intervention in Afghanistan, and permanent occupation”

Our response to the gendered violence of the Taliban cannot be an endorsement of more military intervention in Afghanistan, and permanent occupation. War itself disproportionately harms women as existing inequalities are magnified, and social networks break down. Since the US began their ‘reconstruction’ project in the country in 2002, women and girls have made fragile gains in government-controlled areas of Afghanistan, such as going to school and participating in public life. But feminist networks such as the Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan always opposed the NATO occupation. For them, the impoverishment of war widows, increase of sexual violence, often by government officials and members of occupying forces, as well as the lack of legal protections for women are evidence that the ‘feminism’ of military intervention in Afghanistan was only ever skin deep.

As footage and images of people falling from moving aircrafts disseminate worldwide, arguing in favour of asylum systems based on hierarchies of need whereby women and children get first access is meaningless and cruel. Tweeting out a picture of hundreds huddled into an aircraft baggage hold and asking where the women are once again plays into colonial narratives that brown men are not deserving of safety or care, because they are the perpetrators of violence, and not victims.

In Afghanistan, it is not only the Taliban who are murdering people, but the inherent violence of the border state, which prevents people from escaping, and traps them under authoritarian, fascist rule. As Greece frantically completes a 25-mile extension to its border wall with Turkey to deter Afghan migrants from entering the country, and French president Emmanuel Macron gives a speech claiming France must “protect itself from a wave of migrants” immediately after Taliban takeover of Kabul, it is a feminist’s job to fight for open borders and a safe right of passage for all people. We must not allow our agenda to be set by celebrity activists and commentators who were persuaded by intervention in 2001, nor public figures who set a false binary of military involvement versus total inaction.

Although the right might begin by curtailing freedom of movement along gendered lines only, we only need to look at the growth of anti-migrant rhetoric in the last ten years to know where this ends up. Instead, feminist solidarity is recognising that freedom for women in Afghanistan is freedom for all people to access safety and justice for themselves and their communities, and creating a world where this can be achieved.

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?