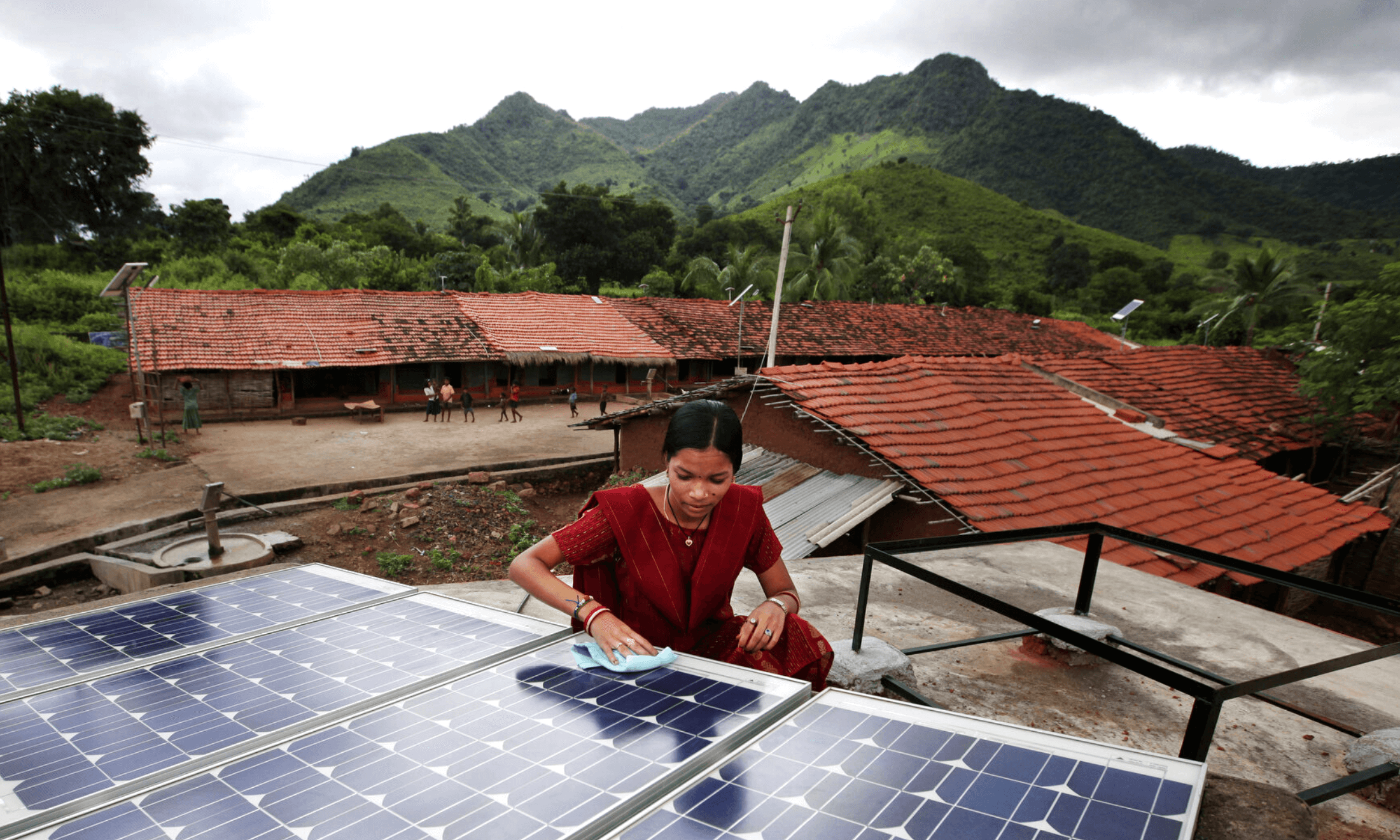

Abbie Trayler-Smith / Panos Pictures / Department for International Development

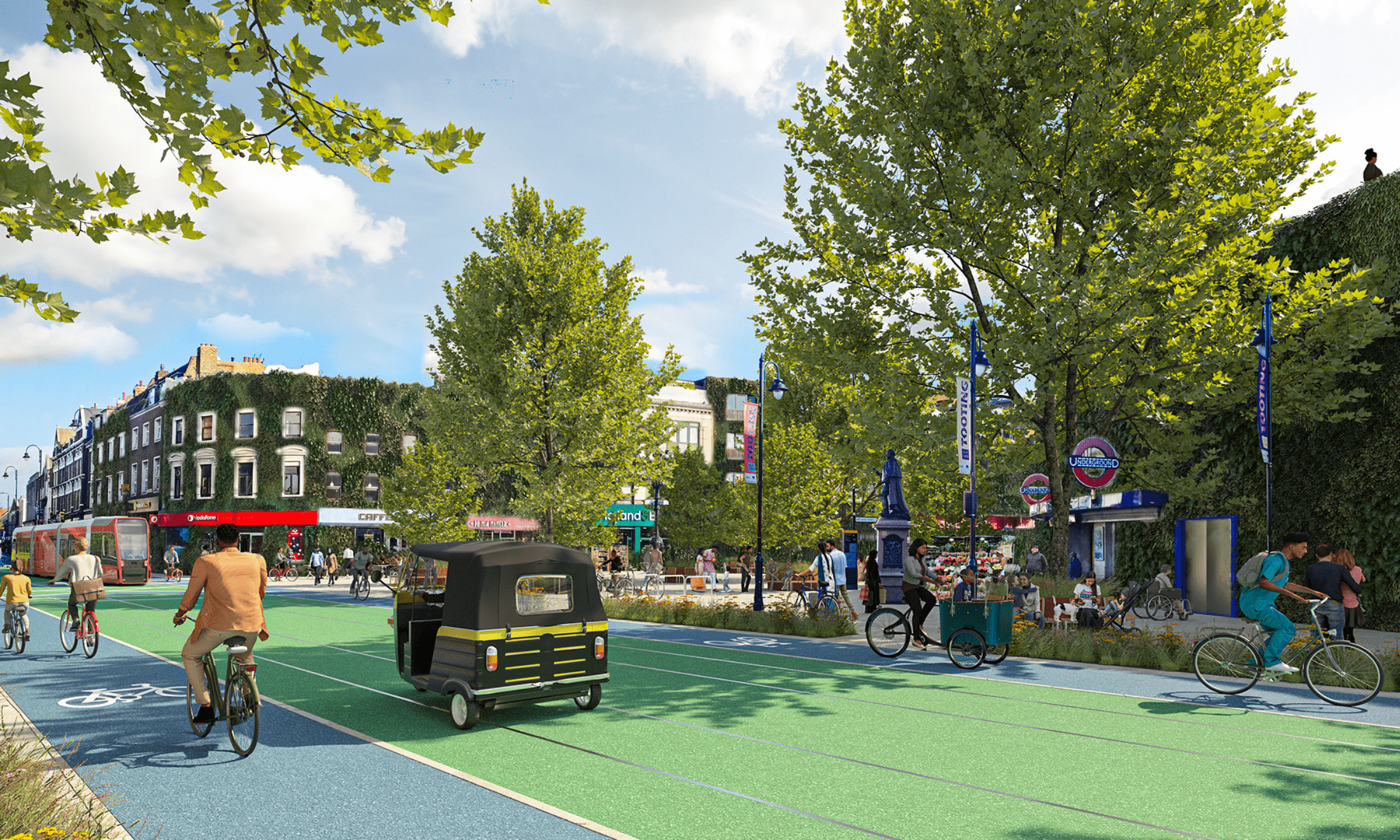

After a gruelling year of heatwaves and floods, Indian climate groups get to work

In India, the unfolding climate crisis has shown no signs of stopping, but work by climate groups is already under action.

Kimi Chaddah and Editors

02 Nov 2022

In May this year, birds, dehydrated and exhausted, began to fall from India’s sky. Animals on the street struggled with the blistering temperatures, while hundreds of bats, crows and peacocks were reported dead.

As the heatwave swept across the country, sweltering temperatures were linked to an increase in heat-related deaths: India’s western state of Maharashtra recorded 25 deaths from heat stroke, the highest death toll in the past five years. These are figures recorded in a country where deaths attributable to a heatwave are already underreported. Northern city Delhi recorded its highest ever temperature of 49C, in what marked the fifth heatwave in the capital since March. As India grappled with scorching conditions, three in five homes faced power outages, and India’s power system was pushed to the limit, affecting hospitals, medical supplies and schools, among other institutions. Due to a fuel shortage, domestic coal supplies fell to critical levels and the price of imported coal soared.

The deadly heatwave in India and Pakistan was reportedly made 30 times more likely by the climate crisis. And the unfolding climate crisis has shown no signs of stopping. This year, floods and landslides triggered by intense monsoon rains killed at least 40 people in northern India in the space of three days, while others were reported missing. Bihar, in the South, is India’s most flood-prone state, with about 75% of its hundred million people affected by the yearly flooding.

“The deadly heatwave in India and Pakistan was reportedly made 30 times more likely by the climate crisis”

“Urban floods are a more frequent phenomenon as a result of changing climate coming together with the encroachment of water bodies, mangroves and urban forests,” explains Dr Ankit Kumar, a lecturer in the Department of Geography at the University of Sheffield. While not on the scale of the 2013 floods which killed 6,054 people and spread across 4,550 villages, India’s oscillating weather typifies the unrelenting nature of the climate crisis facing countries in the Global South.

Despite the horror of unimaginably hot temperatures and devastating flooding, climate organisers are working hard to tackle India’s plethora of environmental issues.

“Our focus is to mobilise urban citizens and make them feel like their rights should be heard”

Citizens Movement was formed two years ago in Bengaluru, by a group of individuals whose main focus at the time was saving their local lakes, particularly in South Bengaluru. The lakes have been subject to drought, extreme heat and invasive, encroaching actions from politicians – such as building hubs for technology companies – like Ecospace in Bellandur – on lake beds. But over time, climate change has quickly become the forefront of the group’s worries. “This month’s rainfall has never happened in all of Bengaluru,” says Mithilesh, an organiser. Meanwhile, weather in other regions is uncharacteristically dry, with 71% less rain than normal.

Mithilesh frequently speaks in terms of individual agency and the power of local, civic action for the community experiencing the wrath of climate change – recognising the disconnection between leaders and locals; between lived reality and widespread apathy. “Our focus is to mobilise urban citizens and make them feel like their rights should be heard,” says Mahesh. “Politicians have some political interest, some financial interest (to prohibiting action that could confront the climate crisis) – nobody takes it seriously,” says Mithilesh. “They do regular duties, but they don’t do anything”, he adds. With increasing population, Mithilesh cites politicians attending initiatives to plant more trees in cities, or attending Environment Awareness days, but little tangible action.

“The environment should be a political issue in election campaigns; it should come in the manifestos of different political parties,” says Mithilesh. “We want to make them aware – the policymakers, the bureaucrats – that if a city gets flooded (because of climate change), nobody will be saved, irrespective of your power status or hierarchy”. Mithilesh holds regular meetings in his locality, currently focusing on an initiative surrounding a lake responsible for the flooding of East Bengaluru. “We are successful in clearing some encroachments,” says Mithilesh, “[but] we’re not able to stop big encroachments by mighty builders linked with politicians”. These encroachments occur when those in power choose to build on lake beds marked as a no construction zone by National Green Tribunal.

The group can currently be supported by joining the movement on social media and sharing their cause, while residents from Bengaluru can participate in their lake rejuvenation efforts.

“In short, farmers and locals aren’t exactly suffering – they’re dying”

Amplifying local campaigns are digital campaigners such as Zero He Se, an initiative stressing the need for the move to renewable energy to be just and fair. While digital, the campaign coordinates protests through social media platforms, like the on-the-ground protest against tree felling in Karnataka, or amplifies ongoing protests, such as an anti-mining one in Odisha. One organiser, Dinesh, who lives in Maharashtra, says the climate crisis is an observable reality: “in Maharashtra, the weather often swings between the extremes – either soaring heat and droughts, or heavy downpours and floods.”

“We do our best to keep the most-impacted people, in India’s local communities, the focus of our campaigns,” says Dinesh, who aims to shed light on the role of privilege in climate (in)action. As well as being one of the most affected by the climate crisis, India is one of the largest greenhouse gas emitters. But this changes when measured per capita, given the country has the second largest population in the world.

“A large chunk of the population consists of poorer people who do not consume much energy or other resources, which means India has a lower per capita emission,” says Dr Kumar. India has a per-capita emission of 1.8 tonnes (t), in comparison to the UK’s 4.5t. And while India was the world’s third highest polluter in 2019, its scale of emissions, 2.88 CO2 gigatonnes (Gt) is less than the highest polluter, China, at 10.6 Gt and second highest (United States at 5 Gt). Referring to the UN’s commitment to halting emissions to keep global temperature rise at 1.5C, Kumar says: “I don’t think political commitments either in India or in the West go far enough to make this possible”.

“(The Zero He Se campaign) talks about climate justice, which puts the most affected people and habitats in focus of our campaigning, because we have an uphill task of making the climate crisis relevant for the population,” he adds. Rising temperatures don’t just affect crops – it makes labour actively more difficult for agricultural workers. And this does not come without consequences – a report on September 13 revealed that 60 farmers had committed suicide in the previous 43 days. These deaths are largely thought to be the result of local farmers being unable to pay off loans and debt after extreme weather and torrential rain ruined their produce. Citing the news report, Dinesh says, “in short, farmers and locals aren’t exactly suffering – they’re dying”.

According to Dinesh, a person’s ability to survive the climate crisis in India is largely a question of financial and societal privilege; a report released by the UN in 2019 described the prospect of an unchecked climate crisis creating “climate apartheid”, whereby those most affluent escape from the crisis they were complicit in creating (by moving to more expensive, habitable areas), while the poorest communities lack the means to survive the worst effects of the crisis. The report predicts that the climate crisis will push 120 million people into poverty by 2030.

“We focus on improving biodiversity, increasing soil fertility, and agroforestry”

In their work with farmers across India, Naandi follows an organic regenerative agriculture approach which implements practices that help mitigate climate change. The organisation, based in Mumbai, actively implements local projects that support farmers’ livelihoods and climate change mitigation, while also keeping a base for research. “We focus on improving biodiversity, increasing soil fertility, and agroforestry, all of which helps the farmer provide diverse sources of income and nutrition,” says Beena, an organiser.

As floods sweep away farmers’ land, Naandi is intensifying its efforts to help farmers survive the climate crisis by working hand-in-hand and implementing manageable steps for farmers to work towards. For example, Naandi regularly works closely with farmers to improve environmental conditions – recently finding different ways to approach the annual burning of crop residue. While it’s seen as a quick way to prepare the farm for the next life cycle, it also acts as a trigger for poor air quality. “The burning of paddy stubble at a large scale is responsible for the Air Quality Index in Delhi,” explains Beena, but Naandi are working to use it as carbon-rich compost for high-quality crops instead.

A global effort is needed

As local organisers toil and begin unravelling the threads that made India reach this place, it’s worth remembering that a global – not single – effort will tackle climate change. The sheer scale of the climate crisis has rendered collective action to address it on all fronts, particularly when, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, we have just 8 years to halve global emissions if warming is kept within the critical 1.5˚C range. Beyond this, runaway temperature increases will become the norm. “What’s important to understand is that on all these occasions,” says Kumar, “poorest people, who have contributed least to climate change, and have little state support, are most affected”. 88% of people in India’s most disadvantaged socio-economic groups, for example, are wage labourers.

As the year slowly draws to a close amidst a backdrop of an unfolding climate crisis, it’s clearer than ever that the climate crisis is inherently a class and social justice issue. “It’s a conversation about the responsibility of Western countries – of their impact, of their emissions, says Smriti Joshi, a 20-year-old climate activist, citing recent floods. “If another heatwave comes, I don’t know how some people will cope on their own, but I do know that we’ll help each other through it”.

The contribution of our members is crucial. Their support enables us to be proudly independent, challenge the whitewashed media landscape and most importantly, platform the work of marginalised communities. To continue this mission, we need to grow gal-dem to 6,000 members – and we can only do this with your support.

As a member you will enjoy exclusive access to our gal-dem Discord channel and Culture Club, live chats with our editors, skill shares, discounts, events, newsletters and more! Support our community and become a member today from as little as £4.99 a month.