Photography courtesy of Universal Pictures

Queen & Slim’s director explains that sex-murder mashup scene

Melina Matsoukas unpicks the sex-murder scene that makes this romance crime drama one of the most talked about films of the year.

Kemi Alemoru

15 Feb 2020

Photography courtesy of Universal Pictures

While there are many memorable moments in Queen & Slim, there’s one scene in particular that stands out. When the titular protagonists finally have sex, the claustrophobia of the car they’ve used as their mode of escape gives way to a passionate blur of moisturised black bodies, locked lips and wandering hands. But just when you’re about to get into it (and truly, who among us has not been waiting for a Daniel Kaluuya sex scene?), suddenly we’re transported to a protest.

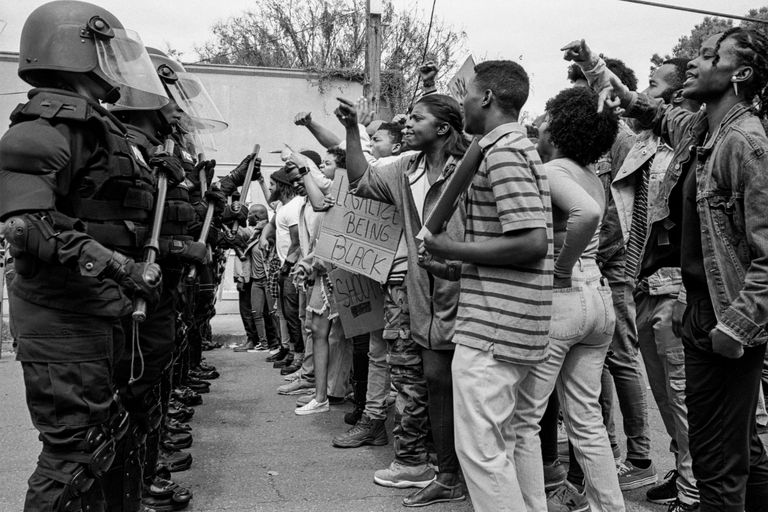

Junior, a teenager we met earlier, is at the epicentre of the unrest. He has followed the story of the pair since they accidentally murdered a police officer and wants to make his mark on the world. In his eyes, Queen and Slim are heroes. The image flicks back to the sex, then to Junior shooting a black policeman in the face at close range. We jump back to the car as their hips grind into each other, then we’re back to the police standoff where Junior has also been shot dead. What… the fuck?

This controversial moment is one that has divided critics. Some believe its strongest element is that it is stylish but it is certainly politically contentious in our current political climate. Does this sex-murder mash-up scene allow the film to fall into the trap of using sex and violence to grab attention and shock, or is it deeper than that? “It’s the moment that Queen and Slim’s relationship climaxes, literally,” explains director Melina Matsoukas, speaking to gal-dem on the eve of the film’s UK release in the plush suites of the Soho Hotel in London. “It’s also the peak of the movement that they’ve created accidentally.”

So far Queen & Slim has made almost £1 million in the UK box office, and around $44.6 million in the US and while some laud it as a “suspenseful, beautifully realised vision” others feel the narrative is messy in parts.

If you’ve seen the evocative romantic crime drama that follows two could-be lovers on the run then you’ll know that above all it is a beautifully shot directorial feat. You’d expect no less from Melina, the woman behind Beyoncé’s ‘Formation’ video, Rihanna’s ‘We Found Love’ visual, and millennial angst comedy Insecure. An avid film buff, Melina says that what drew her to work on this movie was the fact that it was unlike anything else she had seen. “It causes a disruption because it’s a representation of blackness I haven’t yet seen. We were able to cast two very dark-skinned people and I really make an effort to redefine what we see as beautiful,” she says. “Besides Love Jones and Love & Basketball, I didn’t grow up with black love that looked this way.”

In her research, she devoured road trip movies, since Queen and Slim spend so long travelling in their getaway car, and old films like West Side Story, which inspired the juke joint scene in the film. “I also looked at a lot of YouTube videos of real-life, people being pulled over. Like the Sandra Bland video, when she was pulled over by a racist cop and then later died. I related to her so much and wanted the characters to have similar reactions, that moment where you’re being punished for something you didn’t do.”

According to the director, it’s important the release of their anxiety and the violence of the protest happened together because it illustrates how black people have always found moments of joy amid the darkest of struggles. “When you think about the film, it’s about two black people falling in love as the world is burning down around them, right? If you only take those two things and you see nothing else about our film I think you understand our perspective and what we’re trying to say.”

On a technical level, it’s another example of Melina’s impressive commitment to setting the bar high for black sex scenes – as demonstrated elsewhere with her work on HBO’s Insecure. It makes for realistic viewing. “I approach sex scenes out of protection, making sure that everybody’s comfortable with what they’re doing, that no boundaries are crossed, that everybody has consented,” she says. Blazing the trail alongside intimacy coordinators like Ita O’Brien on the set of Sex Education, she put comfort over salaciousness – carefully planning the movements so there was no unexpected touching and filming the scene on a closed set. “I approached it like a dance, like a choreographed routine,” she says.

“It’s the moment that Queen and Slim’s relationship climaxes, literally. It’s also the peak of the movement that they’ve created accidentally”

Melina Matsoukas

“I also think ‘ok we see this part of the woman so we’ll see this part of the man’, making sure that there’s equality between the body parts seen of both actors, so no one feels like they’re being exploited.” Both actors had to be aware of what these particular moments meant in terms of character development and story. “This is the most vulnerable they become to each other, especially Queen who was very protective of herself and takes advantage of this moment.”

This breakthrough moment in their relationship contrasts uncomfortably with the fraught dynamic between black people and the police that plays out on the streets in a Black Lives Matter-esque showdown – although Melina says it is not supposed to represent any particular movement or political organisation.

She explains: “(Black people’s relationship with the police) is complicated. It’s an epidemic going on being killed almost daily by cops.” Her first personal experience with police brutality was going to the apartment where African immigrant Amadou Diallo was murdered by police in 1999. “He was shot 41 times as he reached for his wallet in his apartment in the Bronx. And I remember seeing the bullet holes in the wall,” she starts tearing up. “I’m like getting chills now but my point is he wasn’t an African American he was black in America. This is something that impacts all black communities.”

She adds: “And it’s not only an American issue. Daniel has had his own experience with police brutality and harassment in London. So I really wanted to speak to systematic racism, what it does our institutions, what it does to our communities, and how that applies to the entire world.”

Photography courtesy of Universal Pictures

It’s with all of this passion and confusion that Junior decides to take action. “He gets it wrong, you know, like it’s supposed to represent how our culture influences young minds and how there’s room for a lot of misinterpretation there because they do want to leave a legacy behind.” In addition to this, the fact that the man he shoots appears to be a well-meaning concerned black man (who is, albeit, a fed) is completely intentional. “The institution of enforcement is not black or white. Once you put on that uniform, you’re responsible for the sins of your colleagues,” says Melina. “He sees an enemy who sees him as a monster.”

All of this settles the question of whether this scene was added purely for gratuity and unpicks the uncomfortable racial politics of the violence that unfolds. Whether this translated for you when you first watch the scene or not, what is clear is that Melina is intrinsic to its DNA. To really get it you must first understand how Melina approaches her work. In her words, she’ll always be “a student”, seeking ways to challenge herself and cherry-picking projects with a political element. “My work has a purpose. This isn’t just for the sake of creating or making money,” she says.

Her legacy as a director will be her love of challenging audiences, giving us the room to discuss and interpret the meanings within the film. And this scene is all about what impact we have on each other’s lives. For Queen and Slim as people, their legacy will be their complex and at times ugly and confusing love that they shared for a brief moment. But for those who misunderstand them – both as viewers of the film or onlookers within the story, like Junior, their impact is narrowed down to antagonism and violence.