Canva

A year since Blackout Tuesday, here are the music initiatives still working against structural racism

We speak to the music industry workers for whom Blackout Tuesday spurred a mission of archiving, education and carving out space.

Michelle Kambasha

02 Jun 2021

Like everyone else, the music world was shaken and alarmed by George Floyd’s murder one year ago. Blackout Tuesday (#theshowmustbepaused) – 2 June 2020 – was born in the aftermath, fuelled by the long-standing exhaustion felt by Black executives across the industry. In a statement, Jamila Thomas and Brianna Agyemang laid out some of their grievances: “[We] don’t want to sit on your Zoom calls talking about the Black artists who are making you so much money if you fail to address what’s happening to Black people right now,” the statement read.

The pervading violence of structural racism in the music industry was brought into sharp focus. “Issues of disparity of wealth, power and opportunity have always been a discussion amongst Black peers,” Theo Fabunmi-Stone, a DJ and writer, says to gal-dem. Diversity initiatives in music companies are not new, but often Black execs – people working in the industry as marketers, project managers, booking agents and more – felt they were put in place to placate instead of actively responding to structural concerns like pay inequity and underrepresentation.

And so, the rage became so potent we had to knock down the doors and make record labels, music companies and more actually listen. And we had to create and champion our own spaces.

“For Black people and people of colour within the music industry and on the margins, the day consolidated the pursuit of a long-term mission for equality that, at last, could not be walked back”

The fundamental tenets of Blackout Tuesday and #theshowmustbepaused were simple and resonate a year on: 2 June would be a day for the music industry to unplug, reflect, while Black workers were encouraged to focus on their mental health. Many companies posted a black box on their social media feeds with statements committing to further work beyond that day. In some corners, the day was criticised for being tokenistic, performative and encouraging hashtag activism: especially as the campaign swelled beyond the industry and actors, influencers and questionable corporations started posting the box.

But for Black people and people of colour within the music industry and on the margins, the day consolidated the pursuit of a long-term mission for equality that, at last, could not be walked back. A year on, these initiatives have committed to keeping the legacy of Blackout Tuesday alive.

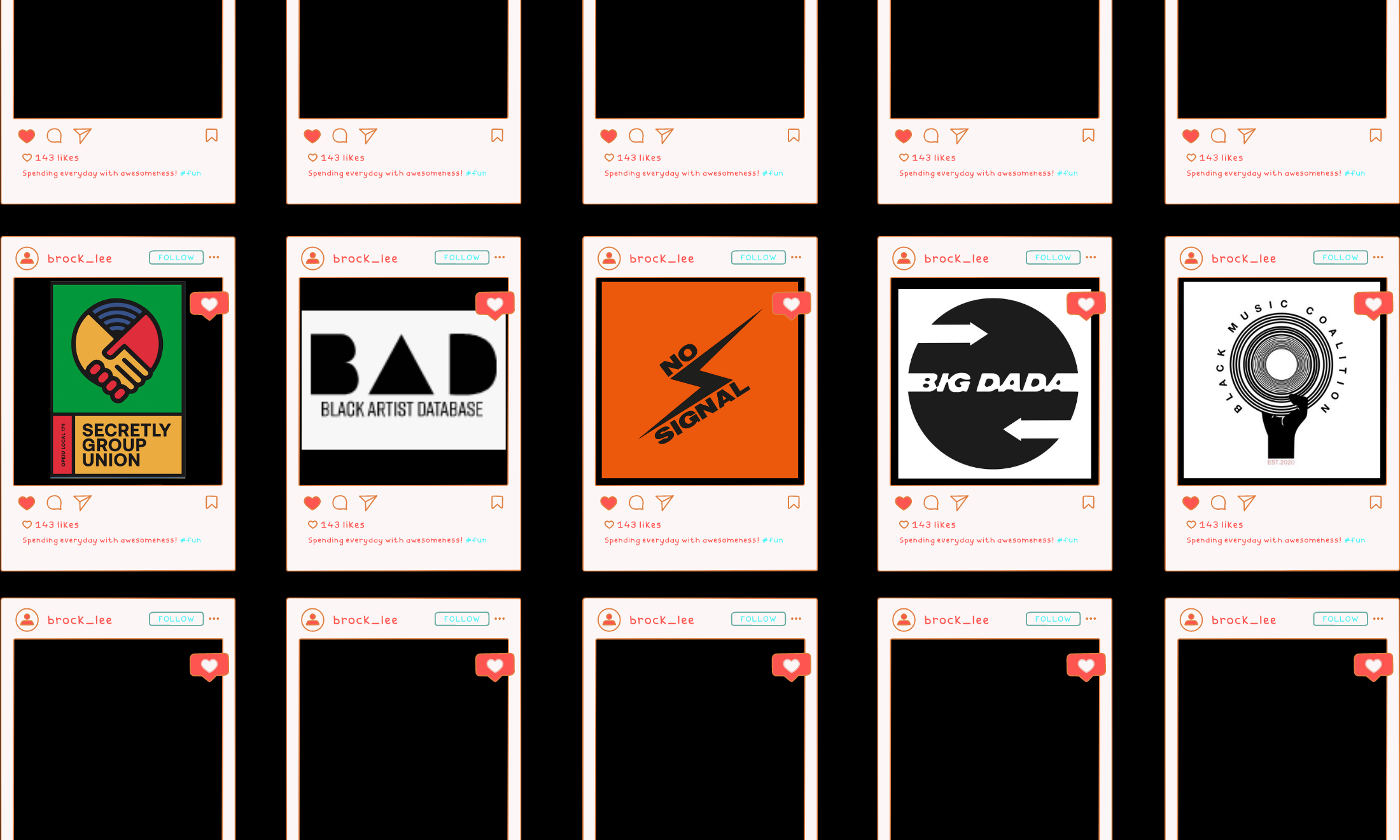

Independent labels

Within the traditional music industry, record labels divide neatly into the majors (now the big three, Sony, Warner and Universal) and the rest – the independents. In April 2021, one of the biggest indies, Secretly Group, announced they would recognise the landmark formation of the Secretly Group Union. For some union members, the racial justice protests of last summer fueled the resolve to address diversity issues through the formation of a union. This was the case for Daria Gwaltney, a Black member of the union and US Projects Coordinator. While some Black workers have experienced microaggressions or blatant acts of racism, Daria herself notes the racialised ‘imposter syndrome’ that comes with being one of the few Black faces in white rooms: “I need to make sure I’m extremely knowledgeable so that I’m never doubted and everyone knows I belong here just like the next person.”

A newer phenomenon that she notes too is how independent labels have diversified their rosters, while much of the staff remained white. While some requests were typical in most unionised labour negotiations: fair pay and a better work-life balance, when the discussions to unionise came up in the aftermath of Blackout Tuesday, diversity was always treated as a top issue. While she admits that even though the majority of the union is white, she has been “personally surprised by the amount of folks [showing up] that are willing and want to change”. While the negotiations are ongoing, the hope is that it sets a precedent for other indie label workers to follow suit.

“The usual decision makers will take a step back so as to not put their commercial ‘white’ filter on these projects”

Victoria Cappelletti

Another independent label that’s taking a different approach is Big Dada, an imprint of Ninja Tune. A historically Black label, Big Dada had lain dormant until early 2021 when they announced the relaunch, noting they would not only release music by people of colour but be run by people of colour. Victoria Cappelletti, one of the label heads, explained that since Blackout Tuesday and even a year on, they have been having weekly discussions with Ninja Tune’s CEO about how they could protect and elevate their POC artists and staff. The thinking behind this decision to relaunch was in response to structural issues at labels, ending the cycle of senior white executives gate-keeping Black and POC artists. Ninja Tune’s staff is diverse, Victoria says, but “we’ve had discussions with artists who [at their previous labels] felt excluded by their label team and worked with people that were not getting it”. The objective for new Big Dada signings is that their label staff will instinctively understand them: “the usual decision-makers will take a step back to avoid leaning into any commercial viability filter on these projects”.

Archives

“I think more often than not, the reason this history hasn’t been properly written is that it hasn’t been written by us”

Theo Fabunmi-Stone

Black Artists Database/[pause]

While some record labels are slowly adapting their structures, others spaces such as the community-based platform Black Artist Database (aka BAD, formerly Black Bandcamp) completely understand the issues that frame Blackout Tuesday. For Carin Addula, a staff member at BAD, the day really hammered home that “mutual aid is a core essential” to the survival of Black music and Black spaces and that “the idea of community and this sense of cohesion” was powerful. Founder Niks Delanancy explains “I’m not trying to be like a utopian socialist, but there is genuine power out there.” Niks notes that BAD wouldn’t have been as successful without the momentum of last summer, which propelled what started out a crowd-sourced list to highlight Black artists to now a database providing visibility for over 3500 Black artists across multiple music genres.

Re-Record: RA and Mixmag’s Blackout series

On Blackout Tuesday, Theo Fabunmi-Stone was working at legendary electronic music site, Resident Advisor. He and other co-workers (including non-Black ones) felt that the electronic music coverage at RA was skewed in favour of white producers and DJs. Additionally, by narrowing the basic definition of electronic – music made on computers – dancehall, reggaeton and even some elements of pop music were excluded, conveniently shutting out Black artists so that “black iterations of [electronic] music need to be diluted until they’re acceptable”. Theo and the other Black contributors co-created RE-RECORD: RA, an attempt to re-educate audiences about Black musicians’ influence on the genre and its lineage, by creating an archive of 120 Black electronic artists from the past 20 years that keeps the legacy of Blackout Tuesday alive. Crucially, Theo wanted all who contributed to the Re-record to be Black. “I think more often than not, the reason this history hasn’t been properly written is that it hasn’t been written by us.” Mixmag have also taken a similar approach with their award-winning Blackout series – in their words, it’s “editorial dedicated to Black dance music history, artists, issues and stories guest-edited by Kwame Safo, aka Funk Butcher.”

Digital Archive For Underground Music

Someone else who understands the importance of archiving to tell our stories is Yewande Adeniran, aka Ifeoluwa, creator of Digital Archive for Underground Music. They believe that, since Blackout Tuesday, Black people have been doing most of the leg work, while the most they have got from white folk is “we’ll try to do better.” Their frustration is steeped in their surrounding city Bristol – a place rich in Black music culture – where at first they naively thought that the dance music culture would be true to its roots. It was not. “It’s a white liberal paradise…and they pretend to not be aware of white structures that essentially benefit them. Any discussion of racism in general, let alone in underground music, is chalked up to misunderstanding.”

“We don’t have a proper grime or garage archive in this country. Considering how influential it is to the charts and pop music…if we don’t record it, we’re contributing to the erasure of Black people and Blackness”

Yewande Adeniran

Their reason for creating the Digital Archive for Underground Music is similar to Theo’s: “We don’t have a proper grime or garage archive in this country. Considering how influential it is to the charts and pop music…if we don’t record it, we’re contributing to the erasure of Black people and Blackness.”

Educational spaces

Aditi Jagnathan’s Rhythm, Race and Revolution

We can keep archiving our music, but Aditi Jagnathan – a PhD researcher and educator – believes it’s also imperative for non-black and white people in particular who work within music production spaces today to critically engage with music. “It should be the point of entry to work in the music industry with Black music and Black artists,” she says, “You have to engage with the history and the conditions that enable that music to be created.” Building off her background in racial injustice organisations and a Goldsmiths course she teaches on race, gender and representation, in early 2020, she developed an independent learning space called Rhythm, Race and Revolution. Using education as a tool for liberation, she facilitates students to (un)learn the different forms of colonial doctrines through the sonic resistance of artists such as Sun Ra to Alice Coltrane. In the aftermath of Blackout Tuesday, the importance of radical education spaces for those of us who make a living in the music industry is clear. Aditi asks, “what would the music space look like if people would love Black people as much as they do Black music?”

Mentors

Raji Rags, a familiar face in the London underground scene from his work as a DJ and host for both NTS Radio and Boiler Room, took things into his own hands to offer free consultancy for Black music creatives. With no application form or cost, he provided a service with no hurdles to participate. Through both 1-2-1 sessions with himself and group calls with Errol from London label Touching Bass, mentees such as Jamiu (an experimental electronic producer) has been mentored by Bristol producer and DJ Batu for the last year. Through the mentoring, Mohamed El-shourbagi’s Egyptian record label, diy records, landed a distribution deal with online record store Boomkat. Naira, a DJ, who now has a Reprezent FM residency through Raji’s introduction, puts it down to the authenticity of the consultancy: “It’s quite easy to do it for the PR but I’ve still kept in contact with him since and it’s genuine support on his end.”

No Signal Academy

The cultural sector has witnessed the huge rise of Black radio station No Signal and its flagship show NS10x10 through the last year. For Jojo, who runs the station, from day dot there has been a priority of handing down knowledge to build the next generation of Black talent, which has resulted in No Signal Academy – a 12-week mentoring programme into the music industry for young Black creatives. Tobi Kyeremateng, an award-winning producer in the arts, joined in June 2020 to set up the academy which launched in April 2021. For her, it was clear that Blackout Tuesday meant that corporations were throwing money at organisations (“Black death again…here’s some money”), and it felt again surface level with no structural change.

“No Signal is successful because the entire organisation is us, it’s us at every single level having these conversations”

Tobi Kyeremateng

The No Signal Academy seeks to reconcile these issues – particularly financial constraints – that work against Black creatives who want to get in the industry. Each participant is given £1000 to take part, with a further budget of £3000 to go towards their radio project. The station aims to create an infrastructure that not only focuses on the public-facing roles (presenters etc), but spotlights the behind-the-scenes roles, because traditionally “when it comes to structurally who is making this work, who is making the decisions… they don’t look like us.” Tobi continues that the success of No Signal is “because the entire organisation is us, it’s us at every single level having these conversations.”

Community

Black Music Coalition

Founded by top music executives Char Grant, Afryea Henry-Fontaine, Komali Scott-Jones and lawyer Sheryl Nwosu in June 2020, the Black Music Coalition endeavours to establish equality for Black workers in the music industry at all levels, by advocating for their right to fair pay and career progression, establishing a formal Black music network. Char says that there was no formal process in the initial days: “people were texting one of us, asking to join and what they could do…we all came together, and the open letter went out.”

“The past year has brought Black people together that were otherwise pitted against each other, by an industry that didn’t care about our pain”

Char Grant

People’s willingness to join is also a testament to a growing trend they’ve seen in the 15+ years of their careers: Black people vocally supporting one another. “Generally, it’s Black people that have supported my journey – they’ve been the ones that have said ‘come let’s go’”, says Char who has worked at labels like BMG Publishing, as well as Modest Management. This past year has been a catalyst for “bringing [Black] people together that were otherwise pitted against each other, by an industry that didn’t care about our pain”, adds Char.

There’s now a more formal structure to the coalition – “an executive committee and an Independent’s subcommittee, who bring forward their own issues”. So far, the Black Music Coalition has partnered up with PRS foundation to launch Power Up: a program for Black music creators and professionals to tackle racial disparity in the music industry.

Blackout Tuesday’s legacy

The legacy of Blackout Tuesday is hard to encapsulate. If the music industry’s racism is a microcosm of wider society, it’ll of course take longer than a year to fix.

A year ago, the three major labels pledged $225 million dollars to racial justice causes – with Warner Music pledging $100 million dollars just a day after Blackout Tuesday – but only a small portion of this has been paid out. It makes Black and POC executives wonder whether their pledge was for positive press and if they are truly committed to long term structural change.

“I think being an ally is a verb,” says Char, “it’s about what you’re making a conscious choice to do.” Allyship in this sense might mean listening to and actioning diversity initiatives that seek to promote Black execs to senior positions, and ensuring pay equality.

“We will continue the legacy of Blackout Tuesday, not just for ourselves but for the next generation”

The industry continues to benefit from and enjoy the fruits of Black labour and art, but as Afryea puts it, “you have to be with us for the blues, you can’t just love the rhythm.”

What we can undeniably conclude is that because of what Ziwe satirically calls “the persistence of women of colour”, we will continue the legacy of Blackout Tuesday, not just for ourselves but for the next generation. Whether it’s preserving our history through archiving, providing educational spaces so that future workers are aware of Black history in music, mentor schemes so we can see people that look like us in senior positions, financial aid that seeks to break down structural constraints and networks so we can connect with one another.

Additional research for this article done by Hagino Tiger Reid.